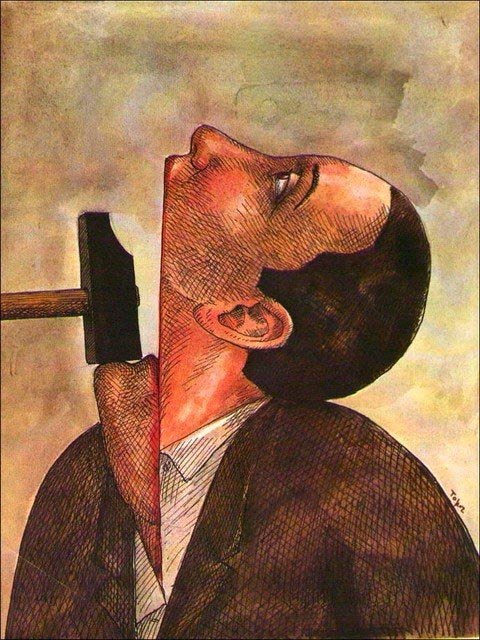

Cartoon by Roland Topor, 1961, used to promote Hara-Kiri magazine.

Roland Topor was one of the most surreal artists of the second half of the 20th century. The French cartoonist gained notoriety in the pages of the subversive satirical magazine Hara-Kiri (later Charlie-Hebdo), before spreading his output to novels, films, songs, theatrical plays and TV shows. Topor's cartoons are strange, disturbing juxtapositions of people, animals, plants and objects, sprinkled with black, absurd and sometimes scatological comedy. He rarely used words in his illustrations, leaving the power to the visual. As a novelist, Topor is best known for 'Le Locataire Chimérique' ('The Tenant', 1964), adapted to film by Roman Polanski. With René Laloux, Topor also co-directed, scripted and designed the animated feature film 'Le Planète Sauvage' ('Fantastic Planet', 1973), which has become a cult classic. Another notorious cult movie by Topor, co-directed with Henri Xhonneux, was 'Marquis' (1989), a strange adaptation of Marquis de Sade's life and sado-masochistic works, featuring actors in animal masks and as puppets. Topor also acted in a couple of movies, with his performance as Renfield in Werner Herzog's 'Nosferatu' (1979) being his most notable role. Topor additionally reached a younger generation with his popular children's TV show 'Téléchat' (1983-1986). Throughout his long and versatile career, Topor received many awards and even after his death, keeps influencing cartoonists worldwide.

Early life and career

Roland Topor was born in 1938 as the son of Abram Topor, a Parisian painter and sculptor of Polish-Jewish descent, who earned his income as a leather designer, selling his merchandise to stores. Roland's sister Hélène Topor gained fame in adulthood as the historian Hélène d'Almedia-Topor (1932-2020), while her son, Fabrice d'Almedia (1963) has also become a notable historian. During World War II, the Topor family, like many Jews, was persecuted. In 1941, Topor's father was arrested and sent to camp Pithiviers, where political prisoners were kept and then deported to extermination camps. Abram Topor was able to escape and, from the summer of 1942 on, went into hiding in Savoy, in the South East of France. There, he and his family worked on a farm under false identities. To hide their Jewish roots, they even baptized their children.

When the war ended, Topor studied art at the École Nationale Supérieure des Beaux-Arts (Institute of Fine Arts) in Paris. He also took a three-year long workshop in engraving from Édouard Goerg. In July 1958, Topor published his first illustrations, including cover art, in the literary and culture magazine Bizarre, led by Jean-Jacques Pauvert. He first exhibited his work in 1960 at the Maison des Beaux Arts, accompanied by a book publication by Bizarre's chief editor Éric Losfeld. Topor wrote stories for the magazine Fiction, while his drawings also decorated pages in the women's magazine Elle.

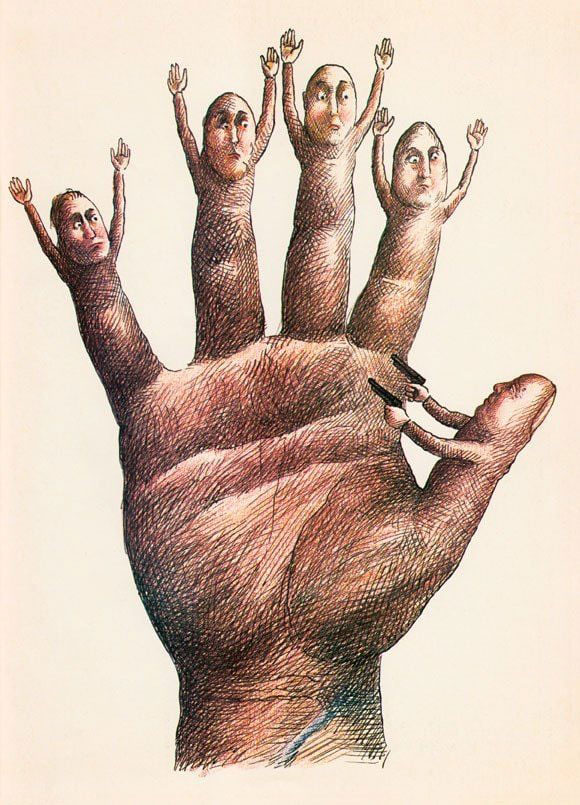

'La Main' ('The Hand').

Style

Since Topor's father was a prototypical "starving artist", he didn't earn much from his paintings and sculptures. It wasn't until after his retirement that he had more time to work on them. Wanting to avoid such an existence, Roland Topor worked hard to get his art noticed and accepted in as many different media as possible. Hara-Kiri chief editor François Cavanna observed that "right from the start, Topor set the bar high for himself and his humorous cartoons (...) He wants it to look aristocratic, as good as oil paintings or chamber music." Topor's illustrations are realistically-drawn in a retro style, reminiscent of the kind of engravings made in the 16th through 19th century, which gives his art a prestigious look.

At the same time, Topor's art is anything but conventional and traditional. The imagery is surreal and macabre. Some scenes are funny, like a thumb threatening four other fingers to hold up their hands. Most scenes have an uncomfortable undertone. Bizarre creatures wander around. People do stuff that seems incredibly ill-thought and dangerous. One gunslinger in pajamas, for instance, uses his own feet at the end of the bed for target practice. In other cartoons, faces and bodies are distorted, chopped off and morphed as if they were made out of clay. Some body parts have grown to enormous size or flow into other parts of the scenery. Topor was a master in creating striking and disturbing images: a rat crawls inside a woman's neck, somebody pulls a nose all the way up to another person's forehead, or a man digs a tunnel through a crowd of people. Topor's illustrations also had an erotic component, for instance: a man is threatened into a corner by a small erect penis. In other drawings, a gigantic erection pressures against a man's chin, or a man hangs from a cliff where a huge penis-faced monster tilts him up to look at a cat with a female face.

Topor's black comedy was shaped by his childhood as a persecuted Jew during World War II. He refused to take life seriously. His philosophy was that "happiness is the only thing mankind ever invented." When asked what he wanted to be, he answered: "God." His self-described favorite pastime was "sleeping". In a 1974 TV interview, Topor revealed that to him sleeping was "working", since his dreams gave him inspiration for drawings. Just like the artists from the Surrealist Movement, he tried to mimic the strange atmosphere of dreams and nightmares in his art. Topor also expressed a dislike for "happy endings" in stories, since they didn't reflect reality.

Nevertheless, Topor adored life, being fond of cigars, champagne and luxurious meals. At his own request, some of his assignments were paid with boxes full of cigars. He had a very loud and memorable laugh, described by many as hysterical and bone-chilling. His art was strongly influenced by J.J. Grandville, Surrealism (especially Max Ernst), Hieronymus Bosch, Pieter Bruegel the Elder, James Ensor, Francisco de Goya, Alfred Kubin, Rembrandt van Rijn, Bruno Schulz, the cartoonist Siné, The Marx Brothers and the scatological plays of Alfred Jarry. Later in his career, Topor also expressed admiration for the work of Kamagurka and Gal (Gerard Alsteens). Topor was equally fascinated with hard-boiled detective novels, "because they feature the best themes: how to survive, how to earn money, and how to save yourself from horrible situations."

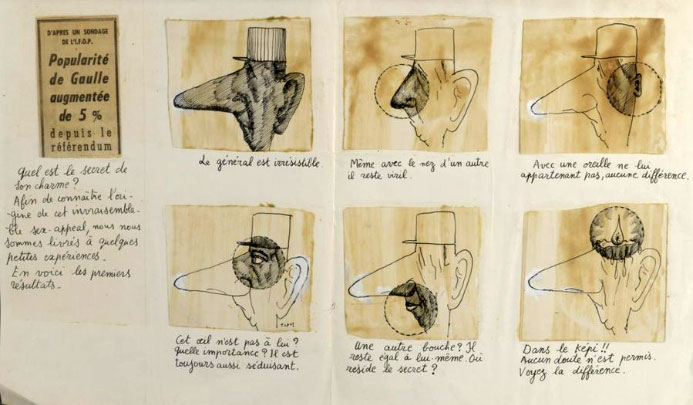

'Quel est le secret de son charme?', depicting Charles de Gaulle.

In the previously mentioned 1974 TV interview, Topor said his work was devoid of a message, or better said: one clear message. "I don't create fables, I create fairy tales (...) There's no moral. (...) I think having just having one moral is always obscene. One moral is not enough. What interests me is ambiguity. (...) The crossroad of explanations allowing one to chose what road one wants to follow." Still, he did have a socially conscious side. During the May '68 student protests, he contributed to the radical but short-lived magazines Action and L'Enragé. When President Charles De Gaulle organized a public referendum to let French citizens decide whether they wanted him to remain in power, he was unexpectedly re-elected by an undeniable majority. Topor then drew a text comic, 'Quel est le secret de son charme?" ("What is the secret of his charm?"), in which a profile of De Gaulle is dissected to find out what makes him tick. Topor discovers that if he changed De Gaulle's nose, eyes, ears and chin, nothing diminished his appeal. Only when he removed De Gaulle's general's cap, his authoritarian appeal was destroyed. In 1977, Topor allowed one of his illustrations to be used to promote Amnesty International. In 1983, when Nazi criminal Klaus Barbie was put on trial, Topor drew Barbie's prostate, depicted as a limp penis behind an SS cap, saying: "Vergès protects me", in reference to Barbie's lawyer Jacques Vergès. In 1988, when the 1938 Kristallnacht was commemorated, Topor made a lino print of a Nazi skull blowing out the candles on a Jewish chandelier (a menorah).

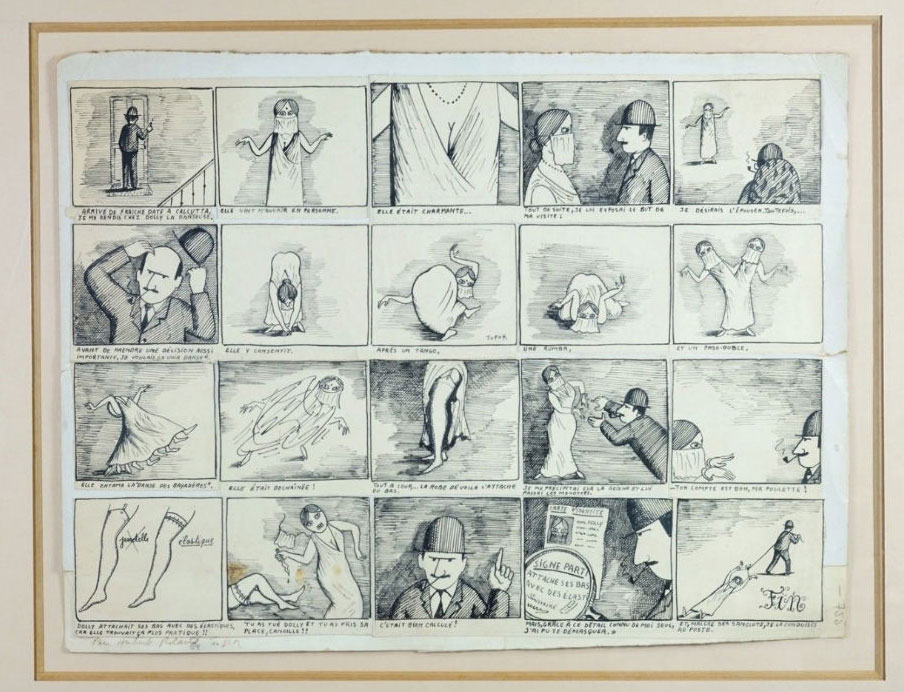

'La Danseuse de Calcutta' (Hara-Kiri #27, April 1963).

Hara-Kiri

In 1961, Topor achieved his breakthrough in the satirical and controversial magazine Hara-Kiri, edited by François Cavanna. Hara-Kiri had a mission to be as outrageous and taboo-breaking as possible. Throughout its decade-long run, it was banned three times. Topor was one of Hara-Kiri's earliest regular contributors, appearing alongside other core contributors like Jean-Marc Reiser, Fred, Wolinski, Cabu and Gébé. However, he was still the odd one out. He didn't draw traditional humorous cartoons or comics and avoided text as much as possible. Some of his drawings made use of sequences, like 'La Danseuse de Calcutta' ('The Danser of Calcutta', issue #27, April 1963), a strange text comic in which a man visits a dancer and afterwards drags her along with him on a rope. Another sequential story was 'Cérémonies Pour Le Corps Neuf' ("Ceremonies For The New Body") in issue #31 of September 1963. In five drawings, Topor depicted a young woman becoming an adult, receiving her first stockings, jewels, bra, lipstick and high heels. Other sequential illustrations by Topor for Hara-Kiri were one titleless story (1961), 'L' Homme et la Mouche' (1962) and 'Le Fils de l' Ivrogne' (1964).

Most of Topor's cartoons in Hara-Kiri, however, were one-panel cartoons. Contrary to his colleagues, he didn't indulge into satire or punchline-based gags, but instead created bizarre scenes that leave the viewer uncertain how to react. From this perspective, his confrontational style certainly fit Hara-Kiri's public image. Nevertheless, Topor left the magazine in 1966 since the work didn't pay enough.

Charlie Mensuel and other publications

Roland Topor's cartoons have also appeared in Charlie Mensuel, Surprise, Vaillant/Pif, Merci Bernard, L'Écho des Savanes, (À Suivre), Hop!, Zoo and Mormoil. In the Netherlands, his work ran in God, Nederland en Oranje (1966-1968) and in Italy in Linus. From 1982 on, Topor published in Le Petit Psikopat Illustré (often shortened to Psikopat), an alternative review which also published work by Willem, Kamagurka, Édika and Carali.

Topor drew several comics for Charlie Mensuel, a sister magazine of Charlie Hebdo, edited by Georges Wolinski. In issue #36 (1 January 1972), he drew the two-pager 'Alfred, ou l' Histoire d'Une Réussite'. Between issue #41 (1 June 1972) and #46 (1 November 1972), Topor drew several comics titled 'La Vérité sur Max Lampin' ("The Truth About Max Lampin"). This mysterious bespectacled character was featured in short events, with a descriptive text underneath the images. Lampin was described as "a piece of shit", who is subject to all kinds of humiliations and accidents. Editor and translator Frédéric Brument later revealed that Lampin was actually a stand-in for the late president Charles de Gaulle, whose death had been mocked by Charlie Hebdo, causing the magazine to be temporarily banned. Collections of Topor's comics were made available by publisher Wombat under the titles 'Strips Panique' (2014) and 'La Vérité sur Max Lampin' (2020).

Theatrical career

In February 1962, Topor was co-founder of the "Mouvement Panique" ("Panic Movement"), together with Alejandro Jodorowsky, Olivier O. Olivier, Jacques Sternberg, Christian Zeimert, Abel Ogier and Fernando Arrabal. This theater collective focused on creating absurd and bewildering performances to reject the commercialization of surrealism. The founders created many provocative and surreal works throughout the 1960s and early 1970s. In 1973, Jodorowsky dissolved the movement, but Topor continued writing and staging scandalous plays afterwards. In 'Le Bébé de Monsieur Laurent' ('Mr. Laurent's Baby', 1975), the protagonist nails a baby against the door of his house. Passers-by wonder whether they should condemn him or admire his audacity. 'Vinci Avait Raison' ('Vinci Was Right', 1976) was a parody of detective stories. A policeman and his wife invite some friends over to stay at their new house for the weekend. Unfortunately, all the lavatories are blocked, which causes shit to spurt out of every toilet, with the inhabitants wondering who is responsible for this mess. Theater audiences in Brussels, Belgium, and the Arts Theatre Club in London seemed less keen to see the mystery of 'Vinci Avait Raison' resolved and left home early.

Together with his good friend, the playwright Jean-Michel Ribes, Topor additionally wrote the theatrical play 'Batailles' (1983) about people of different social classes stranded on a raft, a satirical allegory of capitalism.

Novels and other books

In 1964, Topor published his debut novel 'Le Locataire Chimérique' ('The Tenant', 1964), about a man who moves into a strange apartment. None of the other residents liked him and started bullying and tormenting the poor man, who grews increasingly paranoid and insane. In 1976, this psychological horror story was adapted into film by Roman Polanski. Both Topor's original novel and the film are nowadays considered cult classics.

Topor wrote several other novels and short stories. 'Memoires d'un Vieux Con' ('Memories of an Old Idiot', 1975) featured a man who claims to have influenced countless historical characters, including Sigmund Freud, Al Capone and Jean-Paul Sartre. Topor's 1980s pamphlet '100 Bonnes Raisons Pour Me Suicider' ('100 Good Reasons To Commit Suicide') was another example of his taste for black comedy. Some of the reasons listed were, for example, "because Groucho Marx passed away" (number 88), "to avoid snoring" (number 71), "so I can kill a Jew like the rest of the world" (number 40), "because I have nothing to wear" (number 38) and "because it's the best method to ensure I haven't passed away already" (number 1).

Topor's short story 'Café Panique' (1982) was adapted to a comic book by Alfred (Lionel Papagelli). The most unusual book in Topor's oeuvre might be 'Souvenir' (1972). All sentences in this work were scratched out, making it unreadable. Topor was confident nobody would want to publish it, but, much to his surprise, the Dutch publisher Jaco Groot greenlighted the idea. The unusual book received some media attention at the time. In the Dutch talk show 'Hier Is... Adriaan van Dis', novelist Adriaan van Dis invited Topor for an interview. Van Dis asked him to read a few lines from his strange novel. Topor took the book, held one hand in front of his mouth and started mumbling. He and his good friend Freddy De Vree made another unusual book, 'Cons De Fées' ('The Fairies' Vulvas', Camomille, 1987), which featured a number of erotic poems by De Vree, which Topor livened up with photo collages. The book is notable for its odd triangular shape, mimicking a vulva.

Cover by Roland Topor for Bizarre, July 1958.

Musical career

In 1975, Topor recorded the album 'Panic (The Golden Years)' (1975), which featured his Belgian friend Freddy De Vree interviewing him on the Flemish public radio channel BRT 3 (nowadays Klara). In between conversations, the cartoonist recited nonsensical songs, as well as the Dutch nursery rhyme 'Iene Miene Mutte' and the tongue twister 'De kat krabt de krullen van de trap'. In 2007, the album was re-released on CD. Topor also wrote two songs, 'Je M' Aime' ("I Love Myself") and 'Monte Dans Mon Ambulance' ("Climb Into My Ambulance"), set to music by François d'Aime and in 1980 recorded by the eccentric Japanese singer Megumi Satsu.

Photo comic by Roland Topor (1968-1969). Translation: "Left of me: nothing. Right of me: nothing. Behind me: nothing. In front of me: an idiot!"

Film: poster design, acting career and screenwriting

Roland Topor also had an interest in film. He was interviewed in 'Cartoon Circus' (1972), a Belgian documentary by Benoît Lamy about cartoons and comics, in which he appeared alongside Siné, Picha, Cabu, Jean-Marc Reiser, François Cavanna, Professeur Choron, Gal, Georges Wolinski, Willem, Joke and Jules Feiffer. He designed the posters of movies such as 'L'Ibis Rouge' (1975), 'Ai No Borei' ('The Empire of Passion', 1978) and 'Die Blechtrommel' ('The Tin Drum', 1979). His drawings can also be seen during the opening titles of Fernando Arrabal's experimental film 'Viva La Muerte' (1971), the end credits of William Klein's 'Qui Êtes-Vous Polly-Maggoo?' (1966) and the magic lantern sequence in Federico Fellini's 'Il Casanova di Fellini' (1976).

Topor also worked as an actor, appearing in the aforementioned 'Qui Êtes-Vous, Polly-Maggoo?', Dusan Makavejev's 'Sweet Movie' (1974) and as Dracula's assistant Renfield in Werner Herzog's 1979 horror remake of 'Nosferatu'. Herzog had seen Topor at a press conference during the Festival of Cannes and noticed his notorious high-pitched giggle, which he deemed perfect for playing Renfield, a nervous character possessed by his devotion to the vampire count. Yet he had never heard from Topor and assumed he was an actor. When people informed him he wasn't, Herzog still approached him and Topor accepted the role.

Topor was additionally the (co-)scriptwriter of the comedy films 'Les Malheurs d'Alfred' (1972) by Pierre Richard, 'L'Autoportrait d'un Pornographe' (1972) by Bob Swaim, 'La Fille du Garde-Barrière' (1975) by Jérôme Savary, 'Die Hamburger Krankheit' (1979) by Peter Fleischmann, Gilles Chevalier's 'Le Spectacle' (1984) and Rainer Kaufmann's 'Der schönste Busen der Welt' (1990).

Film career: La Planète Sauvage

Together with René Laloux, Topor created the animated shorts 'Les Temps Morts' (1964) and 'Les Escargots' ('The Snails', 1965), as well as the full-length animated feature 'La Planète Sauvage' ('Fantastic Planet', 1973). The latter work was based on Stefan Wul's science fiction novel 'Oms en Série' and takes place on a surreal planet where gigantic blue aliens treat humans as pets. 'La Planète Sauvage' won the Special Jury Prize at the Festival of Cannes and has achieved cult status over the years. Its psychedelic imagery and bizarre soundtrack are still sampled in music videos and recordings by various bands. In Tarsem Singh's film 'The Cell' (2000), the character Catherine is watching 'La Planète Sauvage'. In the 2002 'Courage the Cowardly Dog' episode 'Tulip's Worm', by John R. Dilworth, a gigantic blue extraterrestrial woman keeps people as pets, in reference to 'La Planète Sauvage'.

Film career: 'La Galette du Roi'

Topor and his friend Jean-Michel Ribes co-wrote the comedy film 'La Galette du Roi' (1985). Set on the fictional island of Corsalina, the plot revolves around the royal marriage between Princess Maria-Helena and Jérémie, son of Victor Harris, "the king of deep-freeze products." The ceremony is interrupted when Prince Utte arrives and declares the wedding canceled for reasons that only become clear later.

Artwork for Roland Topor's film Marquis' (1989).

Film career: 'Marquis'

In 1989, Topor and Xhonneux joined forces again to create the film 'Marquis', loosely based on the life and work of the notorious Marquis de Sade. Set in 18th-century France, it features De Sade as a prisoner in the Bastille. However, it was no conventional adaptation. All actors performed in animal masks. The cartoonist Willem played the fish-headed character Willem Van Mandarine (a pun on William of Orange). De Sade's penis was also anthropomorphized, with the penis glans having a face and the ability to talk. In all aspects a unique and unprecedented movie, 'Marquis' easily became a cult classic.

Radio personality

Topor was a frequent guest in the radio game show 'Des Papous Dans la Tête' (1984-2018) at France Culture. The program, broadcast in front of a live audience, featured many humorous items, scripted by the participating guests. Many novelists, poets, journalists, essayists, playwrights, film directors, actors, comedians and cartoonists have made contributions over the years.

Television career: Merci Bernard/Palace

Topor additionally wrote scripts for the sketch comedy series 'Merci Bernard' (1982-1984), broadcast on France 3, directed by Jean-Michel Ribes. It featured well-known cartoonists from Charlie Hebdo as co-scriptwriters, including chief editor François Cavanna and Gébé, while François Rollin, Jean Bouchaud, Farid Chopel, Pierre Desproges, Jackie Wildau and Jean-Marie Gourio also contributed. The show presented itself as a news broadcast, full of absurd TV reports. Topor and the rest of the 'Merci Bernard' crew additionally contributed to a similar show, also directed by Ribes, titled 'Palace' (1988-1989). Broadcast on the pay channel Canal+, all action in 'Palace' was set in a majestic hotel, where the personnel and customers are daft personalities. Each episode focused on their daily antics, shot in a different location (the kitchen, the elevator, bedrooms, the reception, etc.).

Groucha, from 'Téléchat'.

Television career: Téléchat

In 1983, Topor teamed up with the Belgian film director Henri Xhonneux to create the children's TV series 'Téléchat' (1983-1986) for the French TV channel Antenne 2. The program was a parody of a news show, with all the characters being anthropomorphic animals or objects. The two hosts were marionets, with Lola being an ostrich and Groucha (named after Groucho Marx) a cat. They are surrounded by a telephone, microphone, cutlery, brooms, trash bins and an iron which all have faces and the ability to talk. The show was also broadcast in Wallony on RTBF and in Luxemburg on RTL-TVI.

With its pointed media satire, 'Téléchat' gained a cult following among both children and adults. The program won various awards, including a 1984 award at the Festival of Cannes, for "Best French-Language Show for Children and Adolescents".

'Pinocchio Qui Se Fait Marameo'.

Graphic and written contributions

In 1966, Roland Topor illustrated 'Topographie Anécdotée du Hasard' by the Swiss assemblage artist Daniel Spoerri. The pamphlet featured a detailed map showing 80 objects lying on Spoerri's table on 17 October 1961 at exactly 3:47 PM. He numbered each object, wrote a brief description and his memories about them, while Topor sketched the items. In 1990, Topor also penned the foreword for a reprint of this pamphlet, released when Spoerri's work was exhibited in the Centre Pompidou in Paris.

Topor wrote the foreword for Ronald Searle's comic book 'Homage à Henri Toulouse-Lautrec' (1969). The same year, Topor was one of many artists to make a graphic contribution to Alan Aldridge's 'The Beatles Illustrated Lyrics' (1969). In 1970, Topor collaborated with Belgian Cobra painter Pierre Alechinsky to make a comic strip-like promotional page to promote Topor's latest novel. The comic strip was drawn by Alechinsky with Topor providing text. In 1972, Topor illustrated Carlo Collodi's classic novel 'Pinocchio'. Topor wrote the foreword for a reprint of J.J. Grandville works, published in 1979 by the Éditions Garnier. In October 1984, Topor designed the poster for the annual International Biennale of Drawing in Clermont-Ferrand. In 1992, Topor, Giacomo Carioti and Jean-Louis Colas founded the association ROMALIASONPARIS, which favored a collaboration between French and Italian artists. In 1996, Topor made a special drawing, 'Pinocchio Qui Se Fait Marameo', still used as the symbol on the annual Roland Topor Awards.

Recognition

In 1961, Topor won the Grand Prix de l'Humour Noir for his black comedy. His novel 'Joko Fête Son Anniversaire' received the Prix des Deux-Magots (1970), while at the Festival of Cannes, 'La Planète Sauvage' received a Special Award (1973) and the 1974 Prix Saint-Michel. Between December 1975 and January 1976, Topor's illustrations were exhibited in the City Museum of Amsterdam. In 1981, Topor was honored with the Grand Prix National des Arts Graphiques by the French Ministry of Culture, and, nine years later, the Grand Prix de la Ville de Paris (1990). In 2001, he was posthumously named satrape on behalf of the Pataphysical College. In Paris, the road Passage Roland-Topor in the 10th arrondissement near the Hôpital-Saint-Louis is named after him.

Final years and death

After the death of his father (1992) and additional tax troubles, Roland Topor succumbed into depression. He died in 1997 at age 59 of a cardio-vascular accident.

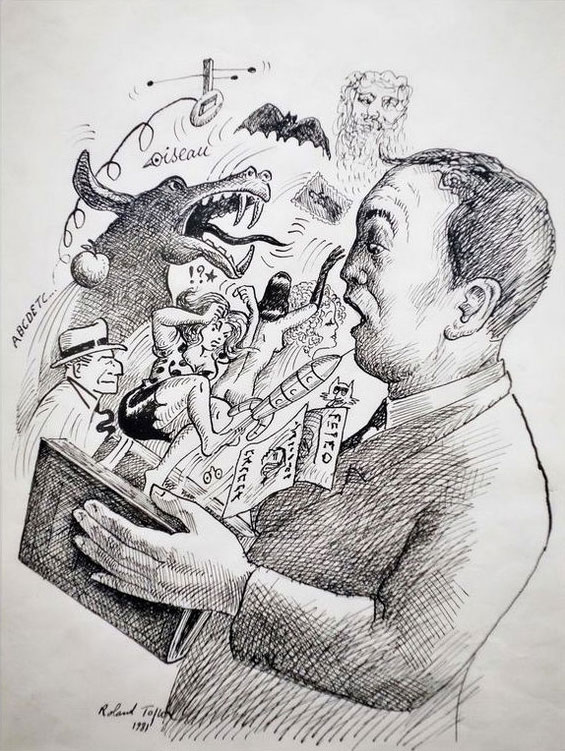

'La Bande Dessinée' (1981). A homage to comics, featuring cameos from Chester Gould's Dick Tracy, Al Capp's Daisy Mae, Jordi Bernet's Clara de Noche, Chic Young's Blondie, Bob Kane and Bill Finger's Batman (as a bat), the rocket from Hergé's 'Tintin' and Gilbert Shelton's 'Fat Freddy's Cat'.

Legacy, celebrity fans and influence

By being active in so many different artistic disciplines, Roland Topor is still rediscovered by many modern artists. Among his celebrity fans have been composer György Ligeti (of '2001: A Space Oddyssey' fame), film director Guillermo del Toro (of 'Pan's Labyrinth' fame), actress Sylvia Kristel (of 'Emmanuelle' fame) and Dutch columnist Arnon Grunberg (who financed a reprint of Topor's work in Dutch). Sylvia Kristel and Ruud den Drijver directed a short documentary, 'Topor et Moi' (2004), in which Kristel reflected on the early days of her career in Paris, with a special focus on Topor. Milan Hulsing provided the animation for this short film.

In France, Topor influenced Emre Orhun and Wolinski, while in Belgium Kim Duchateau, Gal (Gerard Alsteens), Philippe Geluck, Kamagurka, Jean-Louis Lejeune, Erik Meynen, Philippe Moins and Brecht Vandenbroucke are among his followers. Kamagurka, who was a close friend of Topor, named him the main influence on his own absurd cartoons. He also followed Topor's example of being active in many different media. Topor also found disciples in Italy (Sergio Ruzzier), The Netherlands (Willem, Oscar de Wit) and Spain (OPS).

In 2012, the psychological thriller 'L'Orpheline Avec en Plus un Bras en Moins' was released by Jacques Richard, based on a script he co-wrote with Topor in 1996.

Books about Roland Topor

For those interested in Roland Topor's life and career, Frantz Vaillant's biography 'Roland Topor ou le Rire Étranglé'' (Buchet-Chastel, 2007) is highly recommended.

Famous cartoon by Topor, first used for the cover of Mépris nr. 1 (1973), later reused for Amnesty International posters, 1977.