De Avonturen Van Judi 2 - 'Het Wrekende Vuur'.

Karel Verschuere was a mid-20th century Flemish comic artist, and one of the first and most important collaborators of Willy Vandersteen. Working for Studio Vandersteen between 1952 and 1968, he worked almost exclusively as an artist and writer on Vandersteen's realistically drawn comics, such as 'Bessy', 'De Rode Ridder', 'Karl May', 'Biggles' and 'Tijl Uilenspiegel'. For his work on the 'Bessy' series, Vandersteen respected his co-worker well enough to give him a share of the profits and credits under the joint pen name "Wirel". However, the two men later had a falling out, whereupon in 1969 Verschuere started a solo career. He managed to convince some of the other Studio Vandersteen artists to join him, then established his own comic studio and produced western comics for the German publisher Pabel Verlag, namely 'Tom Berry' and 'Jimmy Carter und Adlerfeder'. As his co-workers left him by the early 1970s, his enterprise was forced to close down, after which Verschuere attempted to establish another solo career for the Belgian market, but quickly retired from comics. His falling out with Willy Vandersteen is still shrouded with mystery and contradictive testimonials. The two both accused each other of bad employment, with Verschuere even blaming his old boss for deliberately sabotaging his solo career. Posthumously, Verschuere's reputation was further tarnished by accusations of plagiarism. Still, Karel Verschuere remains an enigmatic personality in the history of Studio Vandersteen, who made significant, graphically stunning and lucrative contributions to the studio's enduring success.

Early life

Karel Verschuere was born in 1924 in Borgerhout, in the vicinity of Antwerp, where his father worked at the Maritime Agency. Verschuere spent his teenage years outside the city, in Deurne. During World War II, he was one of many young people recruited by the Nazis to fight at the Eastern Front against the Russians. After the war, Verschuere was imprisoned for four years for collaboration and treason. In the early 1950s, he and his friend Herman Geerts established their own advertising firm, Gevers. Despite not having any academic training or professional experience, Verschuere was a skilled artist with a good graphic sense of anatomy and perspective, which he had inherited from his father. Verschuere enjoyed reading and drawing realistically-drawn comics, singling out Alex Raymond's 'Flash Gordon' as his main graphic influence. Among the other influences on his comic art were Hergé, Edgar Pierre Jacobs and Hans G. Kresse.

Early comics

In 1952, Karel Verschuere made his debut in Ons Volkske, the children's supplement of newspaper Het Volk, signing his work with the pseudonym "Lerak". His stories, 'Boeren Voorwaarts', 'Strijd om Land' and 'Voor Outer en Heerd' were based on the real-life 1798 Flemish peasant's uprising against the French oppressors, generally known as "De Boerenkrijg" ("Peasants' War"). Verschuere additionally made illustrations for the children's magazine De Kleine Zondagsvriend and the seasonal books of Nonkel Fons at the Catholic publishing company Averbode.

Studio Vandersteen

In 1952, Verschuere's talents were recognized by Willy Vandersteen, who was the most popular and demanded comic artist in Flanders. He had several gag comics, humorous adventure comics and dramatic, realistically-drawn adventure comics running in many different newspapers and magazines, so assistants were always welcome. Verschuere started off inking several of Vandersteen's series, before taking over most of his taskmaster's realistically drawn comic series. Vandersteen taught Verschuere to imitate his style, but he soon had to acknowledge that in terms of realistic drawing Verschuere surpassed him.

Judi/Rudi

One of the first major projects Verschuere worked on under Vandersteen's name was the biblical series 'Judi' (1952-1956). Serialized between 23 October 1952 and 11 March 1954 in Ons Volkske, the series told events from the Old Testament from the viewpoint of a 14-year old boy named Judi. The stories were subsequently published in book format by the Catholic publishing house Sheed & Ward, with ecclesiastical approval from Leo Suenens, the auxiliary bishop of Mechelen and future cardinal of Belgium (1961-1979). 'Judi' was a clear attempt at making wholesome and moralizing Christian comics to appeal to moral guardians. However, most young readers didn't enjoy the comic's dry, serious tone, while Catholic teachers and preachers criticized its liberal and often sensational approach to the Bible. A total of five stories were made. The first three installments were mostly penciled by Vandersteen and inked by Verschuere, while Verschuere wrote and drew the fourth album, 'De Zwervers' (1956), all by himself. This story was no longer serialized in Ons Volkske, but appeared directly in book format. By the time the stories were reprinted in the Ohee series in the 1960s, Verschuere made one final story with the character, who was for the occasion renamed to 'Rudi': 'Het Beloofde Land' (1968).

'Fort Oranje' (1992 reprint in Kuifje magazine).

Tijl Uilenspiegel

For the comic magazines Tintin (Dutch-language version: Kuifje) and Ons Volk, Vandersteen, along with Karel Verschuere, created the historical adventure comic 'Tijl Uilenspiegel' (1951-1953). It was loosely based on the Flemish folkloric character Till Eulenspiegel (Tijl Uilenspiegel in Dutch), and particularly Charles de Coster's rendition from the classic 1861 novel (originally co-illustrated by Félicien Rops). Set in the 16th century, the original novel depicts Tijl as a trickster who frequently fools people, including priests. He eventually becomes "the spirit of Flanders" when he uses his wits to fight the Spanish oppressors. In his adaptation, Vandersteen took the basic premise of Tijl as a resistance fighter, but left out all scenes that were too adult or anti-religious for young readers. He condensed many chapters, added his own imagination and took many cues from artwork by Pieter Bruegel the Elder. Between 26 September 1951 and 24 December 1952, Tintin serialized the first story, 'Opstand der Geuzen', which was a true collaboration between Vandersteen and Verschuere. The second and final installment, 'Fort Oranje', ran between 7 January and 9 December 1953 and brought Tijl and his friends to New Amsterdam in pre-colonial America. This album was almost completely drawn by Verschuere. Other artists who occasionally assisted on 'Tijl Uilenspiegel' were Bob de Moor and Tibet. The comic remains a highlight in Willy Vandersteen's oeuvre.

Suske en Wiske

Despite concentrating on realistic comics, Verschuere sometimes participated in Vandersteen's humorous productions as well. Together with Karel Boumans, he assisted on the 'Suske en Wiske' story 'De Lachende Wolf' (1952) and, together with Vandersteen, he made the special story 'De Rammelende Rally' (1958) for the Antwerp Tourist Federation. The latter was the first 'Suske en Wiske' comic book made specifically for a commercial client, which was not part of the regular series. Verschuere also claimed he was partially responsible for the creation of the character of Jerom. When Vandersteen pondered the idea of introducing a super strong, invincible man in 'Suske en Wiske', Verschuere suggested making him a caveman, inspired by V.T. Hamlin's similar prehistoric character 'Alley Oop'. The name "Jerom" was based on Jeroom Verten, a pseudonymous writer best known as the creator of the farcical plays (and later TV series) 'Slisse & César'. Verschueren also claimed to have thought up the gags in 'De Tamtamkloppers' (1953) and 'De Knokkersburcht' (1953) in which Jerom runs faster than sound, while the text flies out of his speech balloon.

Bessy - 'De Spookhengst' (1954).

Bessy

Inspired by the popularity of the popular film and TV dog 'Lassie', Vandersteen and Verschuere created a more successful blend of adventure and didactics with the 'Bessy' comic. Vandersteen originally asked MGM for permission to create comics directly based on 'Lassie' and even bought a collie dog for inspiration. However, when the Hollywood studio insisted on exact adaptations, Vandersteen decided to create his own series instead, setting all the action in the Wild West. Just like Lassie, Bessy is a female collie, but all action is set in the Far West. Bessy and her owner Andy travel through the prairie with occasional educational intermezzos. Whenever the duo encounters an animal or a plant, captions give readers a small biology lesson. 'Bessy' took off on 24 December 1952 in La Libre Belgique, before making its Dutch-language debut in the weekly Ons Volk (17 December 1953). Starting in 1959, the adventures also ran in the newspapers Het Belang van Limburg and De Gazet van Antwerpen. One story, 'De Gevangene van de Witchinoks', also appeared in De Standaard. In the Netherlands, 'Bessy' ran in the Catholic weekly Katholieke Illustratie (1955-1966), while newspaper De Telegraaf published two stories, 'De Strijdbijl' en 'De Verdwaalden' in 1960 and 1961.

For this series, Vandersteen gave Verschuere co-credit, albeit not under his full name, but as part of the collective pseudonym Wirel ("Wi" for Willy, "Rel" for Karel). Verschuere also received a 20 percent payment of the royalties. No other Studio Vandersteen employee had ever received such benefits. Artistically, Verschuere experimented with lay-outs and panel formats to give the images more dramatic power. His swift pencil put more movement in the characters. As a matter of research, he often worked with real weapons, miniature models and toy trains from his personal collection. His contributions made 'Bessy' very popular among Belgian readers. However, the series had its biggest success in Germany, where between October 1958 and August 1960, Bastei Verlag published the stories in the youth magazine Pony. After that, the 'Bessy' feature ran in Bastei's Felix magazine. Starting on 15 February 1965, full new stories were churned out by Vandersteen's team every month and from the 58th issue every week(!). In the end, about 992 'Bessy' titles were created exclusively for the German market. Some stories were never even translated into Dutch or French. Twenty titles were instantly released as books without prepublication.

To maintain this heavy workload, Vandersteen had to hire new assistants and establish a separate unit of his studio, based in Antwerp. Between 1966 and 1967, Verschuere was head of this 'Bessy' studio, where over the decades, many artists industriously worked on the immense 'Bessy' production: Frans Anthonis, Jeff Broeckx, Chris Callebaut, Eduard De Rop, Eric De Rop, Guy Derrie, Edgard Gastmans, Eugeen Goossens, Peter Koeken, Walter Laureysens, Michel Mahy, Jan Moens, Jacky Pals, Jean Bosco Safari, Frank Sels , Marcel Steurbaut, Christian Vandendriessche, Patrick van Lierde, Ron van Riet, Jos Vanspauwen, Jean Veyt, Jos Verreycken, Robert Wuyts, as did the scriptwriters Jacques Bakker, Daniël Jansens and Hugo Renaerts. After being fired and rehired in 1968, Karel Verschuere drew ten new 'Bessy' stories for the Dutch-language market before leaving the studio for good. The 'Bessy' comic continued in La Libre Belgique until 12 January 1984, and the German contract came to an end in the following year. In 1985, Studio Vandersteen and the publishing house Standaard Uitgeverij made an attempt at rebooting the series under the title 'Bessy, Natuurkommando'. This new incarnation, made in collaboration with the World Wildlife Fund, managed to lengthen the series until after Vandersteen's death, but it was eventually discontinued in 1992.

De Rode Ridder - 'De Zilveren Adelaar'.

De Rode Ridder

In addition to his work for Studio Vandersteeen, Karel Verschuere was also the illustrator of Leopold Vermeiren's popular series of novels about Johan, a noble red knight: 'De Rode Ridder'. Created in 1946, Vermeiren's original stories had been serialized in De Kleine Zondagsvriend, a Sunday juvenile supplement in the newspaper De Gazet van Antwerpen. In 1953, a successful book series was launched by Sheed & Ward, also the publisher of Vandersteen's 'Judi' book. The original 'Rode Ridder' stories were illustrated by a pseudonymous artist named "Jan de Simpele", who was later followed by Gustaaf De Bruyne, Paul Ausloos and then, in the second half of the 1950s, Karel Verschuere. When Sheed & Ward was taken over by the former Standaard Uitgeverij employee Joris Schaltin and turned into the Zuid-Nederlandse Uitgeverij, plans were made for a comic book version of 'De Rode Ridder' with Karel Verschuere as artist. However, both Vandersteeen and Standaard Uitgeverij weren't going to let Verschuere go, and managed to convince Leopold Vermeiren to sign up with them instead. And so, Standaard Uitgeverij became the publisher of both the 'Rode Ridder' novels and comic series. While the novelist greenlighted the comic adaptation, he preferred to have his name removed from the comic book credits because he also worked as a school inspector.

On 5 November 1959, Willy Vandersteen launched his comic version of 'De Rode Ridder' in the newspaper De Standaard. In the original outset, Johan is a lonely knight roaming through woods and fields, fighting for justice. Later, he becomes a Knight of the Round Table and serves under King Arthur and Queen Guinevere. As Vandersteen embarked upon a long trip to SouthEast Asia, the first story, 'Het Gebroken Zwaard' (1959), was mostly written and drawn by Karel Verschuere and Eduard De Rop, based on a short story outline by Vandersteen. Willy Vandersteen wrote and drew the second story, 'De Gouden Sporen' (1960), himself. For the episodes #3 through #15, Verschuere provided most of the artwork. In 1963, he was succeeded by Frank Sels and then Eduard De Rop, until eventually Karel Biddeloo became the comic's longtime writer and artist, turning it into a pure sword & sorcery series.

Karl May and Biggles

While still working on 'De Rode Ridder', Verschuere was assigned to one of Studio Vandersteen's new projects. In 1962, Vandersteen rediscovered Karl May's old cowboy novels about Old Shatterhand and Winnetou, which he had enjoyed so much as a boy. He decided to use the characters in a new comic series, called 'Karl May'. The first story, drawn by Karel Verschuere, was published directly in book format. From 10 December 1962 on, the second episode began serialization in the newspaper De Standaard. Verschuere also drew the second and third story, but then had to leave the drawing to Frank Sels. By then, he was going through marital problems and was often unable to fulfill his duties for the studio. In 1966 and 1967, Verschuere drew two new installments of the series. In the second half of the 1960s, Verschuere also drew the first eight books of Vandersteen's new comic series 'Biggles', based on W.E. Johns' popular aviation novels.

Fall-out with Vandersteen

Despite having a steady, lucrative job at Studio Vandersteen, Verschuere's bond with Vandersteen went through a serious fall-out during the 1960s, spiralling further down from that point on. It all started in 1963/1964, when Verschuere and his wife were going through a difficult divorce. The artist was often depressed and not in the mood to work, and sometimes even vanished for days, trying to escape from his ex-wife and her lawyer. After missing his deadlines too often, Vandersteen fired him in 1964. In the following year, Verschuere was however rehired to draw the 'Biggles' comic. Now remarried, he seemed off to a fresh new start. During this period, Vandersteen also made him head of the 'Bessy' department in Antwerp. But this responsibility came with duties he felt nothing for. In the past, Verschuere could work from the comfort of his home. Now he was expected to drive all the way to the studio to train and supervise the other employees. Another problem was that Verschuere's ex-wife was contractually entitled to her share of her ex-husband's Studio Vandersteen royalties. Verschuere asked Vandersteen to change his original contract, which according to Verschuere never happened.

Already depressed, Verschuere became disillusioned. He felt his employer didn't appreciate what he did for the company. Because, even though he received credit, it was still under the guise of the "Wirel" pseudonym and not under his full name. Vandersteen also never mentioned him (nor his other employees) in interviews. Soon Verschuere stopped caring about his work again, ignoring his weekly 'Bessy' deadlines. Most of his time was spent just hanging about, or playing with his miniature trains. If he picked up a pencil, he just rushed everything out, sometimes not even properly finishing the drawings. As a result, the other Studio Bessy co-workers complained to Vandersteen, requesting for Verschuere's discharge. In 1967, Karel Verschuere was forced to resign. Still, in 1968, he was unexpectedly given a third chance and rehired to draw some new 'Bessy' stories. When he fell back in his bad habits, he left Studio Vandersteen permanently in 1969.

Solo career

Besides working for Vandersteen, Verschuere sometimes worked independently too. Already in 1954, he created the comic strip 'De Avonturen van Koen de Wilde' for Kleine Zondagsvriend, and in 1956 he illustrated Clemence Meyssen's children's novel 'Kiekemieke en Haar Vriendjes'. In 1961, he created a religious comic album about the life of Anthony the Great, 'Fra Antonio - Het Leven van St. Antonius van Padua' (1961), commissioned by the Sint Franciscus Printery. By the time his relationship with Studio Vandersteen became more problematic, he began exploring new opportunities. He tried his luck with creating a new comic series about four adventurers, 'De Avonturen van Klavervier'. The first story, 'Gevaar ronde Co-capsule' (1963), was published in book format by Zuid-Nederlandse Uitgever, the second, 'Avontuur op de Evenaar', appeared in Ohee!, a magazine with a weekly full comic story, published by newspaper Het Volk. In 1967, 'Fra Antonio' was also reprinted in Ohee!, and in the following year, Verschuere made a new episode of the biblical 'Rudi' series directly for this magazine. .

In 1965, Karel Verschuere drew two short stories for the educational historical comic feature 'Les Belles Histoires de l'Oncle Paul' for Spirou magazine. He hoped to become a full-time artist for this Franco-Belgian comic magazine, but this didn't happen. Verschuere always believed that Vandersteen might have had a secret hand in this. With Rik Dierckx as scriptwriter, Verschuere created the western comic 'Buffalo Bill' (1967) for publisher De Goudvink in Schelle. As it didn't have a prior magazine or newspaper serialization, the series failed to capture an audience. After four albums, he left the series, after which two subsequent stories were illustrated by Perry Cotta. In 1968, the four Verschuere stories were also printed in Germany by Bastei Verlag.

Buffalo Bill #1 - 'Het Bizonduel'.

Studio Verschuere

After being fired at Studio Vandersteen in 1969, Karel Verschuere tried to set up his own rival studio, Studio Verschuere, and even convinced the Vandersteen employees Eduard De Rop and Karel Boumans to join him. In addition, he hired Erik Vandemeulebroucke and Frans Anthonis. As he had experiences with the German comic book market through the 'Bessy' and 'Buffalo Bill' series, Verschuere decided to offer his services there. Signing a contract with the German publisher Erich Pabel, Studio Verschuere was assigned to produce the content for the humorous western comic book 'Tom Berry'. Nicknamed "Der pfiffige Vagabund mit Herz und Colt" ("The smart vagabond with heart and Colt"), the blonde Tom Berry was a young and adventurous cowboy who has all kinds of adventures in the Wild West with his blue horse Rosalie and his dog Schnuffi. The series had been started by Pabel Verlag in 1968 as a bi-weekly comic book. In the early years, the magazine's content was made by German artists and then the Spanish art studio Ortega, which assigned Carlos Giménez, José Castillo and Jesus Blasco to the title.

'Tom Berry' by Studio Verschuere.

By 1969/1970, Karel Verschuere had convinced the German publisher that his team could do a better and more lucrative job. Starting with issue #100 (1970), Studio Verschuere took over and the title was renamed to "Der Neue Tom Berry". Verschuere made Tom Berry's looks slightly more realistic, and personally drew the character's heads in the panels. The rest of the artwork was handed to his studio workers. The realistically drawn back-up feature 'Die Abenteuer von Jimmy Carter und Adlerfeder' (no relation to the later US President Jimmy Carter) was drawn by Verschuere himself. The latter comic was also published in the Flemish magazine De Post as 'Arendsklauw'. During Verschuere's tenure, the 'Tom Berry' comic book turned from bi-weekly to a weekly publication rhythm, starting with issue #124. However, the German adventure didn't last long. As Verschuere's employees waited in vain for their payments, they all left him, forcing Verschuere to disband his studio and cancel his contractual obligations to Pabel. By issue #127 (1971), the 'Tom Berry' comic was back in Spanish hands. For a while, Verschuere continued to produce the 'Adlerfeder' comic, aided by the wife of one of Pabel's manager for the inking. A mental breakdown forced Verschuere to retire from his Pabel duties altogether.

Final years and death

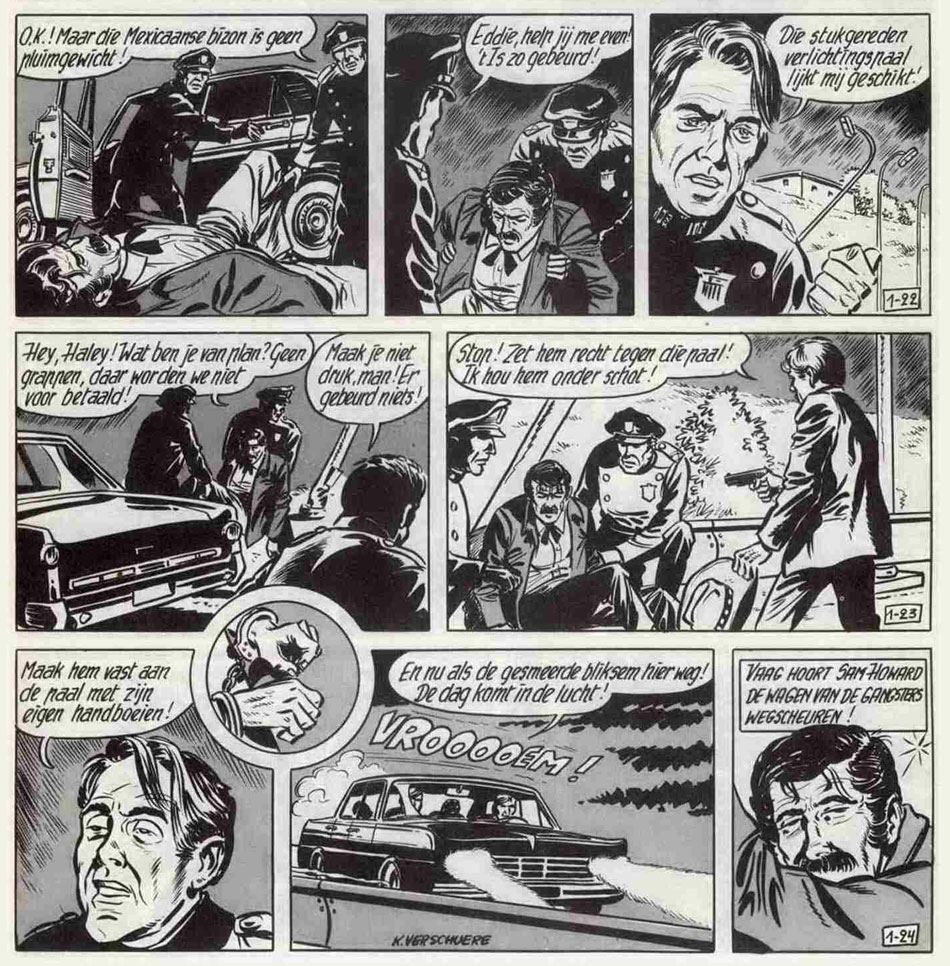

In 1972, Verschuere picked up his drawing pen again, and created three stories of the detective series 'Sam D. Howard' for the newspaper Het Laatste Nieuws. With writer and journalist Marc Andries, he subsequently made two stories with the jungle boy Miguel and the explorer Filip Hechtel for the weekly De Post. Like many of Verschuere's solo comics, these stories also appeared in the Ohee! series. Karel Verschuere eventually retired from the comic industry and went to work at the Rent-a-Car service of Peugeot and for Daniel Construction Company International. For Daniel Construction's staff magazine, he made his final comic project, a gag strip named 'Pamper's Baby'. Karel Verschuere died from cancer in 1980.

Legacy and posthumous controversy

To general audiences, Karel Verschuere's significant contributions to Willy Vandersteen's studio as a writer and artist have remained mostly unrecognized. Since much of his work was done anonymously, Vandersteen fans and comic historians often have difficulties trying to pinpoint his narrative input in Vandersteen's stories, making it uncertain how much credit he actually deserves. Further complicating the matter is the confrontational research of comics experts Jan Smet, Ronald Grossey and Rob Møhlmann, who unearthed many examples of Verschuere plagiarizing entire scenes from other series. Not only in terms of poses or panels, but even plotlines. He frequently borrowed material from Hergé's 'Tintin', Edgar P. Jacobs' 'Blake and Mortimer', Victor Hubinon and Jean-Michel Charlier's 'Stanley' and 'Tiger Joe', Hans G. Kresse's 'Eric de Noorman' and 'Matho Tonga', Harold Foster's 'Prince Valiant', Gustave Doré's bible illustrations and Jean Giraud's 'Blueberry'. Interviewed by Jan Smet for CISO Stripgids #8 (1975), Verschuere admitted that he lacked Vandersteen's richness in ideas and often resorted to plagiarism under time pressure. However, he had no pretenses over a medium he considered a "routine job (...) aimed at children". In Verschuere's defense, Vandersteen was also no stranger to plagiarism, as made public in Møhlmann's 1982 book 'Zwartboek Over Plagiaat', in which it was uncovered that Vandersteen frequently copied from Harold Foster and Alex Raymond.

The exact nature of Vandersteen and Verschuere's soured professional partnership shall always remain a matter of opinion. When Jan Smet interviewed Verschuere for Stripgids in 1975, he made so many controversial claims and accusations that Vandersteen contacted Smet afterwards for a "right to reply", which became a full-blown interview published in the next issue. Vandersteen claimed that Verschuere simply failed to reach his deadlines too often, also because he sometimes went into hiding from his wife's lawyer, as a result of the divorce case. Yet Vandersteen did admit that he should have made an official contract with Verschuere from the start, instead of their gentlemen's agreement from the early days, a mistake Vandersteen never made with any of his other employees again. Verschuere wouldn't be the last controversial Studio Vandersteen worker either. In later decades, Marc Verhaegen left behind an equally disputed legacy as a result of a fall-out.

Karel Verschuere has a cameo at the start of the 'Suske en Wiske' story 'De Klankentapper' (1961). He appears as the bespectacled man in black suit who tries to trick Jerom by pulling a chair away underneath him. He can also be seen in 'De Briesende Bruid' (1968-1969) outside the city hall when aunt Sidonia gets married, alongside other studio employees Eugeen Goossens and Lucienne van Deun.