Hans G. Kresse ranks among the most important and celebrated Dutch comic artists of all time. He became famous as the author of the newspaper comic 'Eric de Noorman' ('Eric the Norseman', 1946-1964), about the adventures of a blonde Viking king. This epic medieval adventure series captivated readers with breathtaking artwork, vivid characters, spell-binding narratives and atmospheric illustrations. Originally a pure fantasy comic, Kresse took 'Eric' to new levels by grounding it in historical reality. He spent many hours of research to get every detail about the time period exactly right. The end result is one of the all-time classics of Dutch comics and one of the few to achieve success in translation throughout Europe, as well as South Africa, Argentina, Brazil and the former Dutch colonies. Apart from 'Eric', Kresse also created other historical comics, such as the spin-off 'Erwin de Noorman' (1966-1974), the Napoleonic detective series 'Vidocq' (1965-1970) and several well-documented stories about Native Americans, including the 'Matho Tonga' series (1948-1949, 1954, 1970) and his 'Indianenreeks' with stand-alone stories (1973-1982). In addition to comics, the talented artist was a much sought-after book and magazine illustrator, appearing with painted illustrations in magazines like Donald Duck, Revue, Margriet, Panorama and Pep. His influence on realistically-drawn comics in the Low Countries has been immeasurable. Together with Marten Toonder and Pieter J. Kuhn, he ranks as one of the "Big Three" of Dutch post-war comics.

Early life and career

Hans Georg Kresse was born in 1921 in Amsterdam as the son of a German-born father and a Dutch mother. His father Ludwig Georg Kresse (1884-1935) was a violinist with the Royal Concertgebouw Orchestra, who had also played with the Philadelphia Orchestra in the USA. However, Kresse hardly got to know his father. About a year after his birth, in late 1922, his parents separated, and Hans went to live with his mother and grandmother. As his mother Henny Jordan (1896-1972) earned the family income as a telephone operator, the boy was largely raised by his grandmother. During his childhood, the family moved around a lot, first to several locations in Amsterdam, and then, after 1931, in Haarlem. As a child, Kresse developed a keen passion for both writing and drawing, and he carefully studied the anatomy books of his maternal grandfather. The books about Winnetou and Old Shatterhand by Karl May sparked his strong interest in Native American culture, as did the Far West novels of the French writer Gustave Aimard and the 'Tecumseh' series by Fritz Steuben. Throughout his life, Kresse collected a great many books about the subject, which he used as documentation for his comic projects.

A high school dropout, Kresse first learned to become a carpenter at the local technical school, but also showed a gift for the arts. In Amsterdam, he followed art classes from the sculptors Mari Andriessen and Jan Bronner, as well as the painter Henri Frédéric Boot. During his youth he already read comics, though he originally had more interest in sculpting. Among his graphic influences were Harold Foster ('Tarzan', 'Prince Valiant'), Milton Caniff ('Terry and the Pirates') and Alex Raymond ('Flash Gordon'), whose realistically drawn action-packed adventure series had a profound impact on him. The 1921 'Three Musketeers' film with Douglas Fairbanks and the Errol Flynn portrayal in the 1938 'Robin Hood' movie also made a lasting impression on his visual storytelling. On 7 September 1938, Kresse was sixteen years old when he published his first comics in the boy scout magazine De Verkenner. His first serial, 'Tarzan van de Apen' ('Tarzan of the Apes', 1938-1940), was fan fiction based on the iconic jungle hero. The teenager showed more originality with his western comic 'Tom Texan' (1940). Around the same time he also illustrated the scouting guide 'Lassowerpen en Touwdraaien' (1939) on how to use lassos and ropes. The book was a translation of the American book 'How To Spin A Rope', but then with illustrations instead of photographs. Afterwards, he found a job in Haarlem as a painter of advertising billboards.

World War II

In the fall of 1940, Kresse offered his services to Marten Toonder, who had already made himself notable during the 1930s by publishing comics in several newspapers and magazines. By the end of the 1930s, Toonder had decided to establish his own studio, which specialized in comics and animation. The timing was perfect, because World War II had cut off the import of American and British comics, creating more demand for locally produced series. When Kresse showed his artwork, Toonder was quite impressed with his eye for visual perspective and characterization, but felt the young man could still use some more training and told him to contact him again later. So instead, Kresse became an illustrator for Kampeer Kampioen, a publication of the "Royal Dutch Touring Club" ANWB, and created book covers for the publishing company Boekenbedrijf Arena in Haarlem. In 1940 and 1941, he also briefly worked with the aspiring animator H. de Vogel in Malden, who worked on a series of folkloric shorts under the title 'Tuyl Uylenspieghels Snakeryen', which were shown in cinemas in January 1942.

In 1941, Kresse received an unexpected letter in his mailbox from the German draft board. Much to his surprise, he wasn't considered a Dutch citizen but a German one. His father had German nationality, and Hans was never naturalized to a Dutch citizenship. The most frightening part about the letter was that Kresse was now expected to serve in the German army. The startled young man went to the recruitment office in Parderborn, but avoided the draft by pretending to suffer from a nervous breakdown. He was so convincing that he was officially discharged for being "mentally insane". However, this didn't let him completely off the hook. He was put under observation in an institution in Bielefeld, where a German military doctor regularly checked whether his condition improved. For months on end, Kresse had to fake his illness, and walk around mumbling to himself. In May 1942, he was finally discharged and he could return to Haarlem. By now, he didn't have to pretend to be a nervous wreck anymore, for he had actually become one. The whole experience left him with frequent attacks of anxiety and paranoia.

Nederland-Film

Back in civilian life, Kresse realized he had to find a permanent job which would make him too valuable to be sent to the front. In 1942, he took part in a drawing contest that earned him a spot in the animation course from Henk Kannegieter. After the course, the participants were contractually obliged to join Nederland-Film, a low-budget animation studio under Nazi supervision. There, the young artists were assigned to work on the antisemitic animated propaganda feature 'Van den Vos Reynaerde' (1943) by Egbert van Putten. However, most of the artists weren't even aware of the product they were working on, since they were only exposed to the specific scenes they were working on. According to Gerrit Stapel, Kresse only worked at the studio for a couple of weeks, and had no involvement in the movie itself. Dutch comic artists who did work on this picture were Jan Bouman, Joop Du Buy and Gerrit Stapel himself. When Nederland-Film was dissolved and absorbed by Barvaria Filmkunst, the artists were relieved from their contracts.

Toonder-Geesink Studio's

In 1942, Kresse's mother noticed that the Toonder-Geesink Studio was looking for animators. Glad to work for the company he wanted to join in the first place, Kresse applied again, and this time he was hired. On 1 May 1943, he became a Toonder-Geesink employee, along with other former Nederland-Film co-workers Hans Keuris and Francis Paid. Since the studio's were working on a film project for the German movie company Degeto, 'Tom Puss: Das Geheimnis der Grotte', the co-workers were exempted from forced labor in Germany. Toonder and his team managed to keep a slow pace, leaving the film unfinished by the time of the Dutch Liberation, but the studio's intact. At first, Kresse was assigned to the animation department, where he worked on a promotional film for Andrélon, and the previously mentioned 'Tom Puss' film. It became apparent that the traumatized Kresse had difficulties working in a team, so he was sent to the comics and illustration department, where he worked alongside Carol Voges and Wim Lensen.

One of his first projects was providing the artwork for the 1943 picture book 'Het Recept van Pinneke Proost' for the gin brand Kabouter. The story was written by Toonder and illustrated by Kresse, along with Henk Kabos, Cees van de Weert and Frans van Lamsweerde, but the book remained unpublished until a 1995 collector's edition was released by John Wigmans. Between 1943 and 1944, Kresse made a realistically drawn comic about the German legend of 'Siegfried' in the biweekly Nazi-controlled children's magazine Jeugd. Since he had to lay low for the Nazis, the comic was credited to his studio colleague Henk Zwart. During the war years, Kresse also made some test episodes for Toonder's comic strip about tugboat captain 'Kappie', which debuted after the war. In addition, he developed a funny animal comic about the bear 'Robby' and the concept for a more realistic comic about a Norseman, all intended for newspaper publication after the war.

'Robby', Trouw, 12 September 1945.

Liberation

In September 1944, the Allied Forces freed the Southern part of the Netherlands, but it took another half year before the North was liberated. Since Toonder's studio was located in the occupied part of the country this didn't instantly change anything for the better. When Toonder learned that the chief editor of his newspaper De Telegraaf was replaced by a Nazi officer, he decided to discontinue his own 'Tom Poes' comic strip. Toonder had the foresight that the Nazis were losing the war and it would be best to distance himself and his studio from them as quickly as possible. During this time, Kresse and other Toonder colleagues made illustrations for the underground resistance magazine Metro and its publisher D.A.V.I.D., while also falsifying official documents for the resistance group of Dick van Veen. On 5 May 1945, the Netherlands were finally liberated. Toonder was accused of collaboration, but able to avoid sentences by pointing out the secret resistance work that he and his co-workers had carried out. In Kresse's case the situation was more complicated. One day, Allied forces arrested him, as he had German nationality and was carrying documents which clarified that he was relieved from German military duties. He was sent off to a POW camp in Overveen, but Dick van Veen personally visited the prison ward to clear his friend of all charges.

Now finally able to breathe again, Kresse could resume his daily life. He got engaged to his girlfriend Bob van Ruijven, a single mother with a daughter from a previous relationship, and the couple went to live together in the forests of Doorn. Due to governmental restrictions to Germans in the Netherlands, it took until 1953 before Hans G. Kresse was naturalized as a Dutch citizen. In that same year, he married his first wife and legitimized her daughter Lineke as his own. The couple divorced in 1959, after which Kresse married his second wife, An Zandstra, with whom he subsequently lived in Maarn and Halsteren, and had one son, Eric (b. 1960) and two daughters, Anka (b. 1962) and Ingrid (b. 1965).

Early post-war comics

Shortly after the Liberation, several of the comic projects Kresse had already worked on during the war saw print. As he didn't feel much for Toonder's 'Kappie' comic, this strip was picked up by Marten Toonder himself, debuting on 27 December 1945. Between 4 September 1945 and 8 April 1946, three episodes of Hans Kresse's funny animal comic strip about the little bear 'Robby' appeared in the The Hague edition of Trouw: 'Robby en de Robijn van den Hertog', 'Robby en het Wintermysterie' and 'Robby en de Schat van de Inca Beren'. The feature was a text comic written by Kresse in collaboration with Dirk Huizinga, with contributions by Wim van Wieringen and Cees van de Weert. The hero was a little bear, obviously influenced by Toonder's own animal comics.

The artist was able to show off his own voice when the non-Toonder comics he had been working on were published in book format. Still in 1945, the publisher J.A. ten Klei Jr. released two comic books drawn by Kresse, both with texts by the retired teacher H. G. Haakenhout. The first was the fantasy story 'Ditto en de Draak in de Grot', based on an initial story by Han van Gelder, the second the science fiction serial 'Per Atoomraket naar Mars'. A scope of his talents was especially given by his first picture books about Native Americans, starting with 'De Gouden Dolk' (1946), published by Dick van Veen's new publishing imprint Buijten en Schipperheijn. In 1947, another picture book about Native Americans, 'De Grote Otter', was published by J.J. van Lint of the Roman Catholic bookstore De Zaaier in Amsterdam. It was reprinted with a revised text in 1952 by MIVA, an organization for missionary workers. This latter book was about a Jesuit priest who dedicated his life to the conversion of Native Americans, and Kresse created it under the pseudonym "Nawada", a name meaning "Great Dancer", which was allegedly given to him by a Native American.

Eric de Noorman: start of a legend

Although at the Toonder Studio's Kresse had been mainly assigned making funny animal comics, he wanted something more challenging, like a dramatic comic series. Already during the war, Kresse had been planning a historical adventure series set in the Middle Ages. Rather than feature knights he went all the way back to the Viking era. The hero was a young, strong and intelligent Viking king called "Leif". The Netherlands have a centuries old seafaring tradition and stories about sailors were always successful. Pieter J. Kuhn's contemporary comic strip 'Kapitein Rob' (1945-1966) was already a hit in the newspaper Het Parool, while Marten Toonder's own 'Kappie' (1945-1972) had debuted the same month with similar popularity. So the idea of a Viking leader traveling the seas in his longship seemed commercially interesting. Toonder however desired a more mystical serial, set in the lost continent of Atlantis, with plots revolving around dwarfs, giants and sorcerers. As a compromise, the two men combined their two concepts, although Toonder renamed Kresse's Leif to Eric. Right from the start, Harold Foster's 'Prince Valiant' was a major source of inspiration. And, in terms of status, 'Eric de Noorman' eventually became Prince Valiant's Dutch equivalent. Like in Foster's comic, the main hero of Kresse's epic Viking saga was a good-hearted and heroic king, who gradually aged over the years.

'Eric de Noorman' - 'De Steen van Atlantis', still with science fiction elements.

Initially, no Dutch newspaper or magazine showed interest in 'Eric de Noorman'. Most preferred humorous children's comics about gnomes and funny animals. Toonder's salesman Anton De Zwaan had to cross the border to Belgium, where the Flemish newspaper Het Laatste Nieuws was willing to give the series a chance. On 6 June 1946, 'Eric de Noorman' took off with his debut story 'De Steen van Atlantis'. Kresse was lucky, because within a year, the Belgian comic industry exploded and oversaturated the market with plenty of comic series of their own. But at the time, Belgian magazines and newspapers were still recovering from the war and could still use young talent, and particularly Het Laatste Nieuws had no successful comic strip yet. Toonder's business partner had correctly assumed that a Viking comic would also do very well in Scandinavian countries. The same year of Eric's Belgian debut, the series also appeared under the title 'Erik Vidfare' in the magazines Kong Fylie (Denmark) and Vecko Nytt (Sweden). Norwegian and Icelandic translations soon followed.

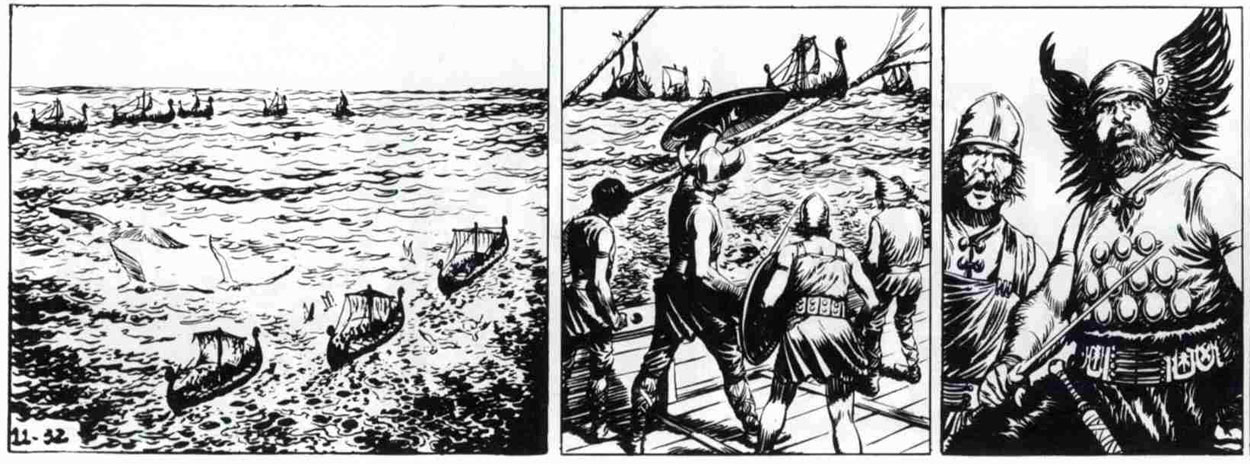

'Eric de Noorman' - 'De Zoon van Eric' (1949).

In the first story, Eric is introduced as the son of king Wogram. He is given the task of finding a bride in the far away country of Franconia. Eric sails off and finds the lost continent of Atlantis, merging Kresse and Toonder's two narratives into one plot line. By the end of the first story, Eric finds his ideal woman, Winonah, and marries her. In the following years, the cast of the series was established. With his wife Winonah he has one son, the short-tempered Erwin. As Eric travelled around a lot, he didn't meet his son until he was seven years old, in the episode 'De Zoon van Eric' (1949). The Norseman king has a colorful bunch of allies. He is flanked by Pum Pum the midget servant, Orm the pessimistic navigator, Svein the combative warrior and Cendrach the veteran ship builder, with his daughter Branwen. Yark and Halfra are two noblemen, but have different personalities. Yark is grumpy, while Halfra is snobby and has a tendency to talk in spoonerisms. Axe and his wife Aranrod are technically friends of Eric, but they frequently quarrel with him and are highly competitive. Still the true villains of the series are the pirate captain Ragnar, the robber prince Baldon and Lauri the cloaked magician.

Between 1946 and 1953, the plots of the stories were conceived in collaboration with Marten Toonder, with Hans Kresse providing all the artwork. And while Kresse was in charge of the overall storylines, the studio assigned additional scriptwriters to help him with story ideas and create the text captions, most prominently Dirk Huizinga, Waling Dijkstra and Jan de Haas, but also Jan Gerhard Toonder and Lo Hartog van Banda. After leaving the Toonder Studio's in 1954, Kresse was in full control of his series, although he occasionally still worked with co-plotters and assistant scriptwriters, including Huizinga, Frans Andrée and Joop Bonhoffer, as well as his mother Henny Jordan and his wife An Zandstra.

'Eric de Noorman' - 'De Wolven van Scorr' (1951).

Eric de Noorman: success

'Eric de Noorman' quickly caught on with Flemish readers. On 25 April 1951, Het Laatste Nieuws launched a separate children's magazine Pum-Pum, named after the dwarf character from the series. Exclusively for this magazine, Kresse and writer Dirk Huizinga created the spin-off 'De Jeugd van Eric' (1951-1955), dealing with Eric's childhood years. For less than two years, Pum-Pum appeared as a separate magazine, but on 25 February 1953 it became a free supplement with Het Laatste Nieuws, appearing every Wednesday. By 1953, Kresse's workload became too heavy, and after a while, Gerrit Stapel and Dick de Wilde often had to take over the art duties. During its final year, the series was completely taken over by Gerrit Stapel. Pum-Pum magazine ran until 11 January 1967. One time, Kresse experienced the popularity of 'Eric' firsthand when he was caught in Belgium for a traffic violation. When the police officer read his identity card, he recognized his name and was in immediate awe. So much in fact that Kresse was allowed to drive along without being ticketed.

While 'Eric de Noorman' did well in Flanders, it took until 28 November 1947 before Dutch readers were introduced to him in the first issue of Toonder's own comic magazine Tom Poes Weekblad. Only when the series took off there, it was finally picked up by Dutch newspapers, starting on 27 January 1948 with De Nieuwe Haarlemsche Courant and De Nieuwe Dag, two newspapers owned by De Tijd. Other papers followed soon after. By 1949, 'Eric de Noorman' was already popular enough to be adapted into a play by Het Vrolijk Toneel under direction of Riny Blaaser. During the 1950s, 'Eric de Noorman' was sold to at least seventeen newspapers in the Netherlands, and many newspapers abroad. While 'Eric de Noorman' invaded the rest of the world, for some of these reprints the text comic was reworked into a balloon comic. The comic appeared in French as 'Eric l'Homme du Nord' in the Walloon newspaper Le Soir and under the title 'Eric le Brave' in the French magazines Aventures Boum, Vécu, Récréation, and Pierrot Champion. English-language readers followed 'Eric the Norseman' in the British papers Liverpool Echo and The Evening Express. In Germany, it could be enjoyed as 'Erik, der Wikinger' in Boni Bilderpost. Finnish readers could follow his adventures in Maaseudun Tulevaisuus, consequently the only language which changed Eric's name, renaming him 'Olaf'. The Norse Viking also appeared in Ireland, Switzerland, Italy, Spain ('Erik, El Hombre del Norte'), Portugal ('Erico, Homem do Norte'), South Africa, Curaçao, Suriname, India, Argentina and Brazil. In Indonesia, 'Eric' was bootlegged as a balloon comic.

Between 1948 and 1962, the 'Eric de Noorman' stories were collected in landscape-formatted comic books, published in the Netherlands by the newspaper De Tijd (initially under its imprint 't Kasteel Van Aemstel) and in Belgium by Het Laatste Nieuws. In the mid-1950s, the comic was at the peak of its popularity, with the booklets reaching print runs of 75,000 copies. Kresse's star was rising, and so was his income.

'Eric de Noorman' - 'De Gouden Droom' (1956).

Eric de Noorman: style and artwork

Like many Dutch newspaper comics at the time 'Eric De Noorman' appeared in the text comics format, with heavy text captions underneath the images. All episodes were printed in black-and-white. Later in his career, Kresse colorized some 'Eric' stories and adapted them in speech balloon format. After inking the first stories with the pen, in 1949 he began using his signature brushwork, which gave his work an even more elegant look. Kresse was a master in light and shadow effects. His characters are often shown in powerful black-and-white contrasts, which give his drawings the feel of a classic silent movie. In a time when the professional Dutch comic industry was still in its infancy, and much of the artwork still looking stiff and unconvincing, 'Eric de Noorman' captivated the reader's imagination like no other, and with international allure. Every scene looked almost photographic, the action was cinematic and the characters felt like genuine people. The text comic format allowed readers to admire Kresse's marvellous and atmospheric illustrations on their own terms. Marten Toonder expressed it best in his foreword to a 1988 reissue of the story 'De Geschiedenis van Bor Khan': "I don't believe that the epic Eric saga would have grown to such proportions if it had been a balloon comic. Not in Kresse's head and not in the fantasy of his countless fans."

Narratively, Kresse had a flair for the dramatics, and often managed to shock his readers, for instance with the death of the popular character Orm the navigator. As the stories progressed, Kresse became more and more personally invested in his series. Since he had largely based Eric's wife Winonah on his own first wife, he hardly used her in his stories since his divorce in 1958. Several episodes showcase the artist's love for nature, and the necessity for mankind to live in harmony with its natural environment. This was for instance exemplified in the episodes 'De Wonderen van Mu' and 'De Vloek van het Goud', where Kresse introduced characters who had turned their backs against materialistic civilization and chose for a life in seclusion.

'Eric de Noorman' - 'De Zwarte Piraat' (1957).

Eric de Noorman: historical accuracy

While Marten Toonder wanted 'Eric' to be a heroic fantasy series, Kresse was more interested in a historical approach. During the first years, magical elements remained omnipresent, although the historical settings became more and more important. Over time, Kresse increased the comic's believability by grounding it more in a plausible reality. Up until 1951 ,'Eric de Noorman' was purely a heroic fantasy series, and Kresse drew the Middle Ages as most people imagined it, without any concern about historical accuracy. Eric encountered magicians, dragons and goblins. The story 'Schipbreukelingen in Rome' (1948) was a turning point. Since the plot involved the real-life Roman emperor Commodus, the artist felt the need of gathering more historical documentation, although this initially wasn't much more than movie pictures. After this particular story, Kresse did more thorough research. His agent Anton De Zwaan once took Kresse on a trip through Scandinavia, where the comic artist collected even more documentation, including a miniature model of a Viking longship.

Eric de Noorman - 'De Witte Raaf' (1954).

While the Rome story was set in the year 192, Kresse eventually chose the 5th century as the permanent setting of his narratives. Most of the sword and sorcery disappeared from the series, although some stories kept mystical elements, like the magical sword of Tyr in 'De Geschiedenis van Bor Khan' (1952-1953). In his later stories, Eric got involved in battles with Celts, Picts, Saxons and Scots, while meeting historical characters like Attila the Hun. In the story 'De Wolf en de Havik' (1955), Eric discovers that his castle has been destroyed and moves into more somber-looking huts, a decision to give his hero a more historically authentic home. The dwarf Pum Pum was also removed from the series, because he was a "magical gnome". The only thing that Kresse couldn't change was Eric's title of "King of Norway". Historically speaking, Norway didn't exist as a nation yet, but Kresse left it the way it was. The artist pushed his quest for realism so far that his characters actually aged and even died. Even Eric grew older as time passed by. At the time this practice wasn't unusual in US comics, Hal Foster's 'Prince Valiant' as a prime example, but in Europe, Kresse was one of the pioneers in this field.

Eric de Noorman: censorship and reductions

From the late 1940s and all throughout the 1950s, comics in the Netherlands were generally regarded as pulp which corrupted the youth and made them too lazy to read real books. 'Eric de Noorman' was one of the few comic strips to escape this prejudice. Fellow artists hailed its masterful artwork and historians acknowledged its historical authenticity. Because of its text comics format and educational nature, 'Eric de Noorman' was deemed acceptable for young readers. The 'Eric' series was popularized by small and cheap books in landscape format, which often told an entire story. While 'Eric de Noorman' wasn't the only Dutch comic sold in this format, it became the one mostly associated with this type and fondly remembered by many comic collectors. However, many books were often edited carelessly. In order to fit everything in, illustrations were often casually cut and stories incomprehensibly shortened. While 'Eric de Noorman' ran uncensored in Flemish newspapers, prudish Dutch censors often took offense with certain "erotically suggestive" scenes. Some male characters walked around bare-chested or wore kilts, while women were drawn with voluptuous breasts and dresses showing some skin. On more than one occasion, certain images were edited to cover up body parts that were too revealing. Sometimes the editors clumsily blacked everything out, making it appear as if characters wore pitch black robes. Some stories weren't even published in the Netherlands, making it difficult for readers to understand the continuity of the series.

Eric de Noorman: later years

By the early 1950s, the 'Eric de Noorman' comic had become so universally popular that it was one of the Toonder Studio's bestselling titles, often outnumbering the syndication of Marten Toonder's own creations. Toonder's salesman Anton De Zwaan claimed that 'Eric' was just easier to sell in foreign translations. To Toonder, it had quickly become clear that Kresse was his most gifted artist. Although he rarely expressed admiration for his employees, Kresse was one of the few he frequently praised during interviews. The only downside was that the Toonder management gave him nearly every assignment, and Kresse often had to work deep into the night to reach his deadlines, but still he was often late with bringing in his artwork. As a result, the studio often paired him with additional scriptwriters to speed up the production, even though Kresse was not the type of artist that liked to collaborate. It also bothered Kresse that many of his texts were changed without the studio's consulting him. Another irritation was the printing quality in some of the newspapers his comic appeared in. In the Liverpool Echo, for instance, 'Eric' was nearly unreadable.

Even though Kresse always expressed gratitude to Toonder for giving him a start, he wasn't completely satisfied by the Studio's policies. As a taskmaster, Toonder often came across as indecisive, never quite knowing what he wanted with the series. In 1951, Kresse took a bold move and applied for a job at the Disney Studios by sending Walt Disney a letter with a few examples of his comics. Although Disney visited Europe and the Netherlands that same year, he couldn't find the time for an appointment. So Kresse stayed in the Netherlands, and continued 'Eric de Noorman'. In 1954, Marten Toonder and Anton de Zwaan parted ways, and the latter began his own company, Swan Features Syndicate. With the separation, the two former business partners divided their assets, with Toonder keeping all of his own comics and the animation studio, and De Zwaan taking with him most of the non-Toonder comics, including Kresse's 'Eric de Noorman'.

Through Swan Features, 'Eric de Noorman' ran for another ten years, during which the series became more historically oriented, completely written and drawn by Kresse himself, with no further creative meddling. However, his collaboration with De Zwaan wasn't completely lucrative either. Kresse had signed a contract that stipulated that he would share half of the profits with De Zwaan. And like before, De Zwaan often had to pressure Kresse to deliver his work on time. After a while, Hans Kresse grew tired of his comic, and on 24 January 1964, the final episode appeared in the papers, concluding the regular 'Eric de Noorman' series after 66 stories.

Xander

While 'Eric de Noorman' was already providing him with a heavy workload, Kresse worked on several other projects during his years at the Toonder Studio's. Over the course of 1946, he developed another historical series, this time dealing with Greek mythology. The main hero is Xander, who is raised by lions and has to claim his birthright, the throne of Mycene. On 31 January 1947, the 'Xander in Hades' comic (1947-1949) debuted in the Swedish weekly Vecko Nytt, and was later that year also printed in Dutch in Tom Poes Weekblad. Presumably written by Jan Gerhard Toonder, the comic was created in the format of Hal Foster's 'Prince Valiant', with text captions appearing inside the panels. After only two stories, however, the series came to an end.

Detective Kommer

Unfortunately, the Toonder Studio's also assigned him with less inspiring jobs, such as the two stories of the detective comic 'De Lotgevallen van Detective Kommer': 'De Armeense Tweeling' (9 December 1947 - 29 January 1948) and 'Het Geheimzinnige Afgodsbeeld' (16 June - 28 July 1948). Published in the newspapers De Nederlander and Het Dagblad voor het Koninkrijk der Nederlanden, this detective comic was based on an old unused script by Toonder, and rewritten by production chief Dick Tonnis (1914-1985). However, the workload proved to be too heavy, and 'Detective Kommer' was canceled to give Kresse the time to concentrate on his other work.

Matho-Tonga

For Tom Poes Weekblad, Kresse also illustrated the feature 'In de Tipi' (1947), which explained the daily lives of Native American tribes. Kresse's passion for the Native Americans was once again showcased in the balloon comic 'Matho-Tonga, Laatste der Mandans' (1948-1955). The comic tells the story of John Kent, a geologist/gold prospector, whose expedition through the Black Hills confronts him with the feared Native American leader Matho-Tonga, who, just like Chingachook of the Mohicans, is the last of his tribe. The 'Matho-Tonga' comic was notable for its strong statement against the mistreatment of Native Americans by the European settlers.

Initially created by request of the magazine Ons Vrije Nederland, the comic had a fragmented publication history. After a first story published in Ons Vrije Nederland, the second one appeared in Algemeen Dagblad, followed by two more Kresse serials in the Belgian weekly De Zweep. The comic was also published in Scandinavia, Belgium, France and England. For his fourth story, Kresse was assisted and/or replaced on the artwork by Dick de Wilde and Piet Wijn (strips #124 through #128). The fifth and final story was created by writer Dirk Huizinga and artist Gerrit Stapel. In 1970, 'Matho-Tonga' was reprinted in Pep magazine. Seven years later, Oberon released two black-and-white book collections of the series.

Commercial comics

By the early 1950s, Kresse also ventured into the field of commercial art, expanding his horizon outside of the Toonder Studio's. Through the Lintas advertising agency, he drew a series of advertising comic strips for Royco soup (1952), published among other places in De Telegraaf and Libelle. Later that decade, when he was already affiliated with Swan Features Syndicate, Kresse was also present in Olidin, the promotional magazine of the Shell Junior Club, produced by the Van Maanen advertising agency. During the magazine's first year, Kresse drew the chivalry text comic 'Roland de Jonge Jager' (1957), followed by two stories of the science fiction comic 'Pim en de Venusman' (1959-1960). It is unknown who the writer for these two features was. Other notable contributors to Olidin were Emile Brumsteede, Wim Giesbers, Frits Godhelp, Friso Henstra, Niek Hiemstra, Jan Kruis, Ted Mathijsen, Joost Rietveld, Chris Roodbeen, Jan van der Voo, P. Visser, Dick Vlottes, Carol Voges, Joop Wiggers and Piet Wijn.

Illustrations for the text serial 'Randar de Bevrijder' by Dick Dreux, which was serialized in Donald Duck in the first half of 1961.

Illustrator

Even though creating his several comic series often left Kresse overworked, he still accepted almost every assignment he was offered. Besides his affiliations with the Toonder Studio's and Swan Features Syndicate, Kresse personally offered his services to publishers and other potential clients. By 1953, Kresse began a second career as an illustrator, which proved equally profitable. His first client was the children's book publisher Van Goor in The Hague, but the collaboration didn't last long because of creative differences. More fruitful and enduring was his association with the magazines of De Geïllustreerde Pers (GP), and later also De Spaarnestad. Between 1953 and 1965, Kresse illustrated many adventure text serials for the Dutch Disney weekly Donald Duck. These included original stories by Dick Dreux, Joop Termos and Tim Maran, but also classic stories by Enid Blyton ('The Famous Five'), Rudyard Kipling, Jules Verne and Robert L. Stevenson. As one of the magazine's first local contributors, Kresse helped earn Donald Duck its firm roots in Dutch culture to this day. By the mid-1960s, he disappeared from the pages of Donald Duck, as he had become a prominent illustrator of text serials in Pep magazine. He, for instance, illustrated Pep's 'Arendsoog' serials by Paul Nowee (1965-1967). His illustration work for Pep also included painted cover illustrations with characters from translated foreign comics. In the final segment of his career, during the 1980s, Kresse returned to the pages of Donald Duck with painted illustrations of fairy tales and classic stories like 'Rip van Winkle' and 'The Legend of Sleepy Hollow'.

Cover illustrations for Pep issue #38 (18 September 1965) and #3 (15 January 1966).

Besides comic magazines, Kresse was a popular illustrator in other magazines, often for editorial sections and spreads on historical subjects. Highlights in Revue magazine were the well-documented historical series 'Van Tinnen en Transen' ("Of Tins and Ramparts", 1956), 'Avontuur en Romantiek Op en Rond de Zuiderzee' ("Adventure and Romance on and around the Zuiderzee", 1957-1958), 'Avontuur voor de Boeg' ("Adventure Ahead", 1959), 'Onze Voorvaderen op Vrijersvoeten' ("Our Forefathers on the Prowl") and the painted centerfolds about world conquerors. Some of these Revue series were also published in the German magazine Praline. Between 1953 and 1964, he provided the illustrations for the sections 'Ik Heb U Lief' ("I Love You") and 'Het Liefdesleven van de Groten der Aarde' ("The Love Lives of the Greats of the Earth") in the women's weekly Margriet. He was also a notable illustrator for Margriet's seasonal books and its children's book library. Between 1955 and 1963, Kresse showed his sense of humor on the covers of Panorama magazine with nearly forty cover paintings, this time in a contemporary setting.

"Ze Veroverden De Halve Wereld' - 'De Profeet greep het Kromzwaard", from Revue/Praline magazines (1958).

While early on Kresse provided either black-and-white illustrations or drawings that were later colorized at the publisher's art studio, after 1962, he began making painted illustrations. When the 'Eric de Noorman' comic had come to an end, these detailed and well-documented painted illustrations became Kresse's focus. Through Swan Features, he also made the painted picture story 'The Story of Hiawatha' (1957) for the British magazine Playhour and Chick's Own, although this was a one-time excursion. His illustration work for magazines also landed him regular assignments from youth book publishers. For Malmberg, Kresse, for instance, made the cover illustrations for Paul Nowee's 'Arendsoog' series (1962-1980) and the 'Pim Pandoer' books by Carel Beke (1963-1964), and for H.J.W. Becht, he was a cover and interior illustrator for the series 'Karl May's Reisavonturen' and Enid Blyton's 'De Vijf'. Between 1961 and 1967, he was an illustrator for several installments in the historical book series 'Geschiedenis en Cultuur voor Jonge Mensen' by Jaap ter Haar for publisher Van Dishoeck. Kresse also illustrated the publisher's collections 'Fibula Junior' (1969-1974) and 'Fibula Klassieke Reeks' (1971-1972). Another book series with Kresse illustrations was Ray Franklin's 'Winfair' (1966-1968) by the publisher Elsevier.

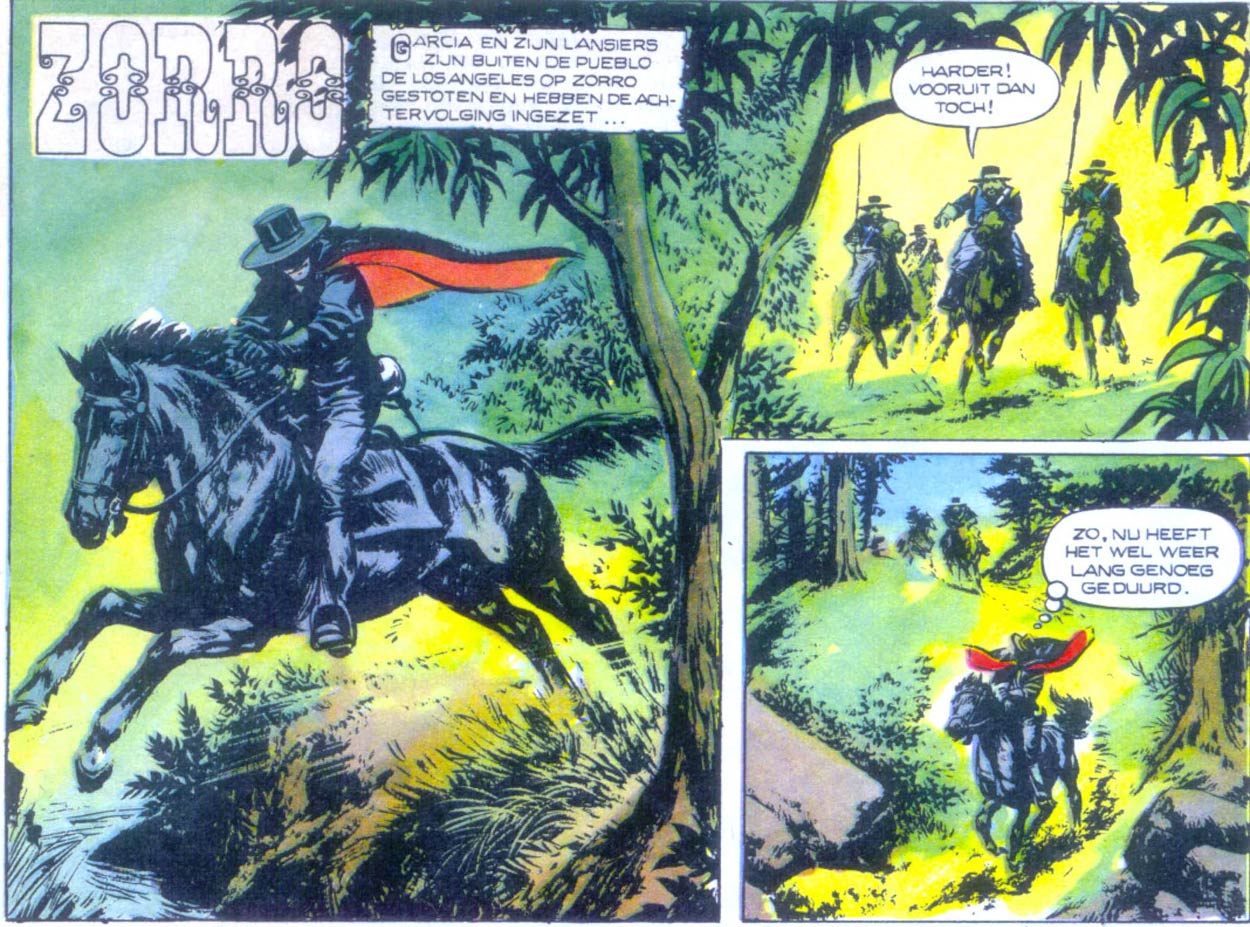

'Zorro' (Pep #52, 26 December 1964).

TV tie-in comics

After discontinuing 'Eric de Noorman' in 1964, Kresse came to the conclusion that times had changed. The traditional Dutch text comics were losing their popularity in favor of the more modern balloon comics. While he was already providing Pep magazine with painted illustrations since 1963, Kresse also began a steady production of comic stories for the magazine. Since the start, Pep magazine had been a mix between locally produced comics, translated Belgian comics and licensed comics from popular Disney live-action TV series. When the American source material dried out, Kresse and writer Joop Termos began creating new stories directly for the Dutch market. Besides two short stories based on the TV series 'Spin and Marty', Kresse became most notable as the artist of nearly 40 short stories with the masked vigilante Zorro, whose adventures had been drawn in the USA by Alex Toth. In the same fashion, Kresse also drew eight short stories based on the TV series 'Bonanza' for Revue magazine. For Pep issue #43 of 1965, Kresse additionally illustrated the one-shot comic story 'De Boogschutter', written by Yvan Delporte. After these initial "works-for-hire", Kresse began providing Pep magazine with more personal comic projects.

Vidocq

Kresse's best-known contribution to Pep magazine was the 'Vidocq' series (1965-1970). Based on an idea by editor Anton Weehuizen, a huge Francophile, the series was set during the early 19th century when Napoleon conquered Europe. The main character was based on the legendary Eugène François Vidocq (1775-1857), a burglar-turned-detective whose memoirs had a tremendous influence on the detective literature genre. Initially working with his chief editor Peter Middeldorp as co-plotter, Kresse once again used extensive documentation for this colorful and atypical comic hero. The master of disguises was accompanied by the sexy Annette, who became his wife, and the redheaded servant Coco as comic relief. Kresse created a total of 23 short stories and 9 serials, four of which were written by Tim Maran. Between 1986 and 1987, the character made a comeback in Pep's successor Eppo/Wordt Vervolgd. Besides two reprints, Kresse made three new stories written in collaboration with Ruud Straatman.

In 1970, De Geïllustreerde Pers released a first book collection with 'Vidocq' stories, and later that decade two new books were published by Oberon. Translations appeared in France and Italy, among other countries.

Native American series

As mentioned before, Kresse had a lifelong passion for Native Americans and their culture, and was utterly disgusted by the brutal way the European settlers had treated them. Early in his career, he had already covered the subject in his picture book 'De Gouden Dolk' and the 'Matho-Tonga' comic series. During the 1940s and 1950s, he was one of the first comic creators to give respectful and accurate depictions of Native American history, culture and customs, instead of the stereotypical portrayal of "cowboys and indians" in western culture. A member of scientific organizations like the American Anthropological Society, the New Mexico Historical Society, the Institute of American Archeology and the Society for American Archeology, Kresse had filled his library with much documentation about Native Americans and their history.

By the time he began illustrating text serials for Donald Duck and Pep, Native Americans became a recurring subject, for instance in the 1954 serials he wrote and illustrated for Donald Duck: 'Tom in de Greep van de Zwartvoet-indianen'. At Pep magazine, he expanded this work with 'De Schreeuw van de Dondervogel' (1968-1969) and 'De Indiaanse Opperhoofden en Hun Oorlogen' (1971-1973), two illustrated serials written by Anton Kuyten (AKA Quint) about important persons from Native American history. During the early 1970s, he also made several comic stories about the subject, starting with the short story 'De Wraak van Minimic' (1970) and then continuing with the comic serials 'Mangas Coloradas' (1971-1972) and 'Wetamo' (1972-1973), the latter two again collaborations with Anton Kuyten.

These first comic stories paved the way for a more ambitious project that would keep Kresse occupied during most of the 1970s. During this period, much of his illustration work dried up, and the artist had more time to embark upon another major comic series. In 1972, Kresse signed a contract with the Belgian publishing house Casterman for a comic saga that would follow an Apache family across multiple generations. Nine stories in total were completed: 'De Meesters van de Donder' (1973), 'De Kinderen van de Wind' (1973), 'De Gezellen van het Kwaad' (1974), 'De Zang van de Prairiewolven' (1974), 'De Weg van de Wraak' (1975), 'De Welp en de Wolf' (1976), 'De Gierenjagers' (1978), 'De Prijs van de Vrijheid' (1979) and 'De Eer van een Krijger' (1982). A tenth volume was left unfinished, but was posthumously published by the Hans G. Kresse Foundation in the book 'De Lokroep van Quivera' (2001). The series never received any other name but the 'Indianenreeks' (the "Indian series") and was recognizable by a font sporting the head of a Native American chief in the upper right corner of each book.

The first installment kicked off with chief Chaka and his two sons, the friendly but headfirst Anua and the self-centered and arrogant Unda. In his stories, Kresse paid a lot of attention to the everyday life of Native Americans, including their philosophies of life and relationship to nature. He also portrayed the Apache's encounters with other tribes and the colonial settlers. In his initial concept, Kresse planned to follow the Apache family over a period of 200 years, starting approximately in 1580. However, he discovered he had too much to tell, that by the time he was at what turned out to be the final installment of the series, only five years had passed. In interviews, he jokingly remarked that if he was to continue at this rate, he would have to become 300 years old.

Although translated in French, Swedish, German, English, Icelandic, Norwegian, Italian, Portuguese, Danish, Croatian, Finnish and Indonesian, the series was never a commercial success. Over the years, Kresse gradually lost his enthusiasm in the project, as he was not satisfied with Casterman's fees and promotion of the books.

'De Zang van de Prairiewolven'.

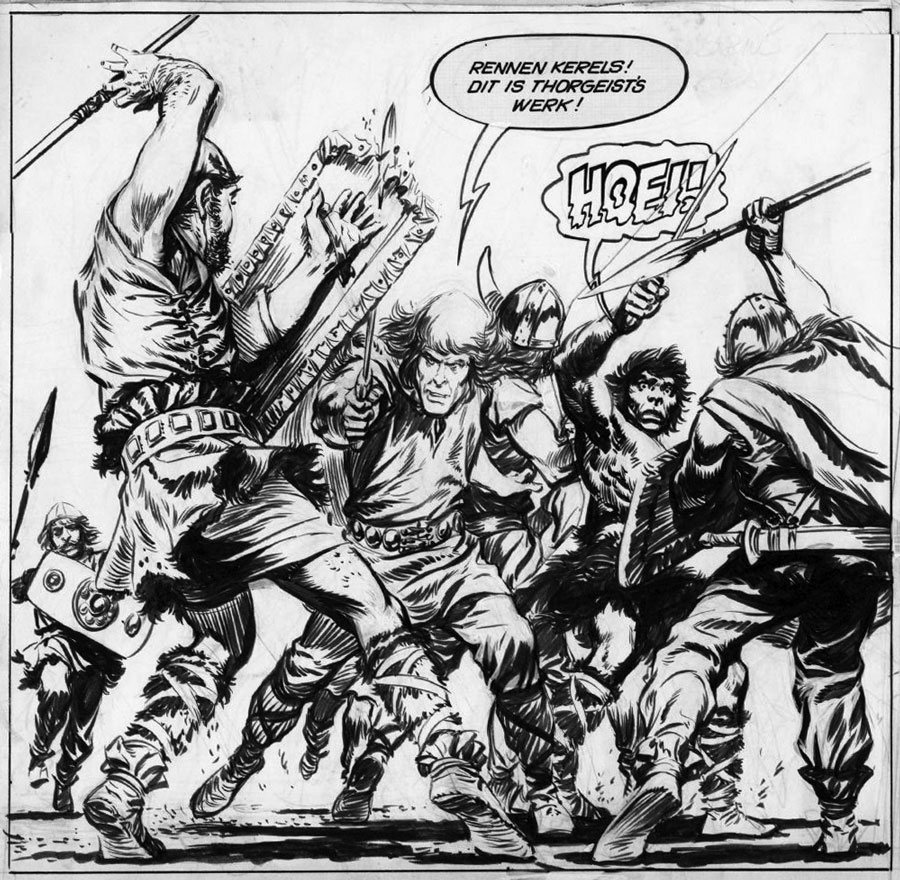

Erwin de Noorman

While at Pep, Kresse's editor Peter Middeldorp requested the return of 'Eric de Noorman' in his magazine. After some debating, it was decided that Kresse would launch a spin-off, focusing on Eric's son Erwin. In line with the new wave of flawed comic characters that emerged in Belgian magazines, Erwin was far from the perfect hero his father was. He was unsteady, made regrettable mistakes and had temper issues. Graphically, the comic switched from the classic text comic format of 'Eric de Noorman' to a colored balloon comic for 'Erwin, de Zoon van Eric de Noorman' (1966-1973). After several years creating short stories of four to eight pages long, Kresse also began creating 'Erwin' serials, starting with 'De Vrijbuiter' (1969) and 'De Geweldenaar' (1970-1971). His final effort, 'De Ware Koning', ran for nearly sixty pages, but was aborted in late 1974, as Kresse had difficulties tying the plot together. This marked his final contribution to Pep magazine, which merged in the following year with Sjors into Eppo magazine.

Erwin de Noorman - 'De Bevrijding' (Pep #5, 4 February 1967).

Revival of Eric de Noorman

By the late 1960s, the first generation of post-war comic book readers had become adults, and began uniting itself in the new phenomenon of "comic fandom". This resulted in a renewed interest in the classic comic books from the 1940s and 1950s, most notably 'Eric de Noorman'. The new wave of collectors was particularly interested in the final twelve stories of the newspaper strip, which had never been collected in book format. In 1969, the publishing company Wolters Noordhoff made a first attempt reprinting the 'Eric de Noorman' series, but gave up halfway through. Other publishers like Tango and Skarabee stepped in, but also backed out after a few releases. In 1980, the Dutch comics collector Hans Matla made a deal with Kresse to reprint all of the 'Eric de Noorman' stories in chronological order in a luxury format through his publishing house Panda. The first volume appeared in 1980, the final one in 1991. All the original artwork and writing was restored and every instance of censorship removed. Most of the restorations were in hands of the long-time Kresse admirer Dick Matena. In 1998, Matla began releasing a new and improved series of his luxury series 'Volledige Werken Eric de Noorman', which had newly edited texts and also included the 'Erwin de Noorman' stories.

Erwin - 'De Vrijbuiter' (1969).

In addition to the reprint series, Matla also made plans with Kresse to relaunch 'Eric de Noorman' as a newspaper comic. With Matla as his agent and main investor, Kresse made several efforts over the course of the 1980s to find a new format for the 'Eric de Noorman' comic. He tried a new text comic style, as well as a balloon version, but all attempts were nipped in the bud. For the 1985 anthology book 'Wordt Vervolgd Presenteert', Kresse produced a new short story with his famous Norseman, 'De Vrouw in het Blauw', but this remained the only completed story.

In 1988, Kresse reworked the 1952 'Eric de Noorman' newspaper text comic 'De Geschiedenis van Bor Khan', and adapted it into a balloon comic for Eppo's successor Sjors & Sjimmie Stripblad. The idea had been suggested by Thom Roep, who had just done the same with Alfred Bestall's 'Rupert Bear' stories for Donald Duck magazine. The sequel 'Svitjolds Offer' was considered for a remake too, but stranded after only 11 pages.

'De Geschiedenis van Bor Khan', balloon version.

Final years and death

The last two decades of Kresse's life were troubled by bouts of depression, failing eyesight and marital problems. A huge blow was the death of his mother, in 1972, which caused the return of the anxieties and paranoia he had suffered during the war. His production slowed down considerably. In addition to his "Indian series", Kresse began working on a new comic serial, this time for Eppo magazine. A magical history series about a Knight Templar, 'Alain d'Arcy: Satanseiland' (1977-1978) was filled with hallucinogenic, almost nightmarish sequences, which Kresse connoisseurs have attributed to the artist's depression.

When his second marriage ended in 1983, Kresse moved to an apartment in the town of Doorwerth, where he spent the final eight years of his life. During the 1980s, Kresse created some new 'Vidocq' stories, but his 'Indian series' stalled out, as did all of the attempts at restarting 'Eric de Noorman'. Over the course of the decade, Kresse took new illustration assignments from Donald Duck weekly, and also from the popular science magazine Kijk. Between 1982 and 1988, Kresse painted book covers for Westfriesland, the publisher that also released his youth novel 'De Kleine Heldin' (1987). His final project was a comic series about Genghis Khan, but only 17 pages were made before he passed away from lung cancer in 1992, at age 70. Hans G. Kresse's death made headlines all over the Netherlands.

Recognition

In 1976, Kresse was awarded the Dutch Stripschap Prize for his entire body of work. In the following year, the sixth installment of his 'Indianenreeks', published in France under the title 'Les Peaux Rouges', won the Prix Alfred for "Best Foreign Comic Book" at the International Comics Festival of Angoulême, France. In 1997, Hans G. Kresse was posthumously made an honorary member of the Dutch Illustrators' Club (NIC). In the comics district of the Dutch city Almere, three streets have been named after Kresse characters since 2003, namely the Matho Tonga street, the Winonah street and the Eric de Noormanhof. There is also a street and a bridge named after the artist himself, the Hans G. Kresseweg and the Hans G. Kressebrug. Since 2023, Hans Kresse also has a bridge named after him in the city of Amsterdam.

Illustration for 'De Witte Hengst Moina' by Marja Schilling (Donald Duck #24, 17 June 1983).

Kresse fandom

Hans G. Kresse was known as a humble, and at times grumpy man who felt he wasn't exceptionally gifted. According to him "anyone could learn his skills" and he famously referred to himself as a "plaatjespoeper" ("shitter of pictures"). He wasn't a social type and preferred staying at home rather than go out and meet his fans, the press or other people. However, he at least lived long enough to experience the appreciation many other veteran artists never received. Two years before his death, an official fan club was established, the Kressekring (1990), which had its own fanzine: Viking. The group also released postcards and silkscreen prints with Kresse artwork. In 1997, these initiatives evolved in the Stichting Hans G. Kresse, with official participation of the artist's children and grandchildren. The foundation has safeguarded Kresse's legacy and provided its benefactors with newsletters and reprints of obscure and previously unpublished works.

Since 2006, a group of 50-60 Kresse fans have been organizing annual gatherings during which the work and life of Hans G. Kresse are studied and discussed. Among the group's core members are Kresse scholars like Eric Planting, Rob van Eijck, Hans Matla, Julius de Goede and Rob Aalpol. On 29 May 2010, Frits van der Linden opened his own Kresse Museum in Gouda. Because of these many private initiatives, the Kresse foundation saw its main goal fulfilled, and announced its dissolvement in July 2018. The final newsletter appeared in November 2018. Kresse's manuscripts and published works have been transferred to the Comics Documentation Center of the University of Amsterdam, while the author's personal correspondence remained within the family.

Expositions

Posthumously, the work of Hans G. Kresse has been the regular subject of expositions, for instance in May-August 1998 in the Frans Hals Museum in Haarlem. During the 2003 'Arnhem Stripstad' exposition in the Historical Museum of Arnhem, Kresse was prominently featured. The Comics Museum in Groningen, opened in 2004, also presented a lot of Kresse material in its permanent exhibition. In 2008, the museum hosted the Kresse exposition 'De Vele Gezichten van Eric de Noorman' ("The Many Faces of Eric de Noorman"). On the occasion of the 60th anniversary of 'Eric de Noorman' in 2006, the city of Arnhem organized several festivities, including an exposition of original artwork at the Presickhaeff's Huis and the installment of several enlarged pictures of 'Eric de Noorman' on walls in the city. In 2021, the centennial of the artist’s birth, the Story World museum in Groningen also exhibited artwork by Hans G. Kresse. In 2024 and 2025, the Museum Veluwezoom in the castle of Doorwerth hosted the career-spanning exposition 'Kunst van Kresse'.

Illustration for the book series 'Geschiedenis en Cultuur voor Jonge Mensen' by Jaap ter Haar.

Influence and legacy

In their 2024 biography book 'De Kunst van Kresse', the authors Rob van Eijck and Rutger Zwart concluded that the graphic style of Hans G. Kresse has no direct followers. Largely because his graphic versatility has been unsurpassed, but also because as a solitary worker, Kresse never had any assistants or pupils. Still, the overall quality of his work and the iconic status of 'Eric de Noorman' have inspired several young men to become comic creators themselves. One of the most notable Kresse fans was Dick Matena, who became close friends with the artist during the final years of his life. Matena also once drew an erotic parody of 'Eric de Noorman', published in the Dutch edition of Playboy magazine. As one of Europe's foremost realistic comic artists, Hans G. Kresse inspired Dutch comic artists like Harry Balm, Theo van den Boogaard, Caspar ten Dam, Anco Dijkman, Jan Kruis, Martin Lodewijk, Dick Matena and Piet Wijn. In Belgium, he found admirers among Rik Clément, Bob De Moor, René Follet, Jijé, Claus Scholz, Frank Sels, William Vance, Willy Vandersteen and Karel Verschuere. Comics like 'De Rode Ridder' by Willy Vandersteen and Karel Verschuere and 'Reinhart de Eenzame Ridder' by Rik Clément' often imitated his graphic style, and sometimes copied entire poses and characters. Clément's Reinhart the knight was, for instance, an obvious expy of Eric. In France, Kresse influenced Jean Giraud and in Poland Grzegorz Rosinski.

All three of Hans G. Kresse's biological children have turned to creative professions. Based in Arnhem, Eric Kresse has worked as a portrait artist, graphic designer and illustrator. His sister Anka Kresse has been a freelance graphic designer, art director and illustrator, as well as a Typography teacher at the ARTEz University of the Arts. Ingrid Kresse in turn has been working as a fashion designer and art instructor.

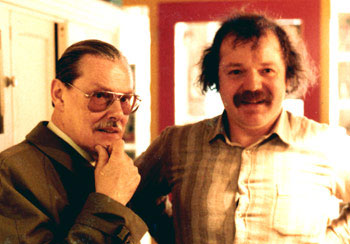

Hans G. Kresse with Lambiek's Kees Kousemaker in 1983.

Books about H. G. Kresse

Dick Matena published a personal reflection on Kresse's achievements, published in the landscape format under the title 'Herinneringen Aan Een Mythe. Hans G. Kresse's Eric de Noorman' (1998). The book was an extended version of an earlier article by Matena, named 'Mijmeringen Bij Een Oeuvre'. In 2007, the equally insightful booklet 'Eric de Noorman Opnieuw Bekeken. 60 Jaar Nederland's Grootste Stripheld' was published by Rob van Eijck, with a foreword by Dick Matena. It provides readers with an overview of Kresse's entire life and career, once again presented in landscape format. In collaboration with Hans Kresse and his heirs, Kresse scholar Julius de Goede released many collections of old and obscure Kresse comics and illustrations. In 2010, he reflected on his friendship and collaboration with the artist in the book 'Over Hans G. Kresse: Herinneringen aan een Meester'. At the opening of the 2024 Hans G. Kresse exposition at the Castle of Doorwerth, the massive Kresse biography 'De Kunst van Kresse' was presented. The book was a true tour-de-force by Rob van Eijck and Rutger Zwart, and can be considered the definitive Kresse overview. Hans Kresse's son Eric provided much of the book's unique illustration material, and also did the image editing and graphic design.

Lambiek will always be grateful to Hans G. Kresse for illustrating the letter "E" in the encyclopedia book 'Wordt Vervolgd - Stripleksikon der Lage Landen', published in 1979.

Illustration for the text story 'Stevijn Hazehart', published in 1965 in Donald Duck weekly.