Pat Sullivan was an Australian cartoonist, animator and film producer, best known for his involvement in the creation of the iconic cartoon series 'Felix the Cat' (1919). While Felix wasn't the first animated character, he was the medium's first superstar. During the 1920s, 'Felix the Cat' was the most popular and mass-merchandized animated series on the planet, and one of the first cartoon characters adapted into a comic strip. Despite Felix' iconic fame, even a century later, there is still controversy whether Sullivan or his employee Otto Messmer created Felix and who played the biggest part in the happy cat's global success. Earlier in his career, Sullivan was also a newspaper comic artist, although none of his series ever caught on.

Early life and career

Patrick Peter Sullivan was born in 1887 in Paddington, New South Wales, Australia, as the son of a Darlinghurst cab proprietor. After leaving school, he worked various jobs, including as gatekeeper at Toohey's brewery in Surry Hills. He attended classes at the Art Society of NSW, while doing his first assignments as a caricaturist. Between 1904 and 1907, he submitted humorous cartoons to the trade union newspaper The Worker, and to the weekly magazine The Gadfly, signing them with "P. O'Sullivan". In 1908, Sullivan emigrated to England, where he tried his hand at singing and dancing in music halls, before eventually making his money as an animal handler on trans-Atlantic ships. His first comics work were contributions to the 'Ally Sloper' strip for a year and a half (originally created in 1867 by Charles Henry Ross and Émilie de Tessier).

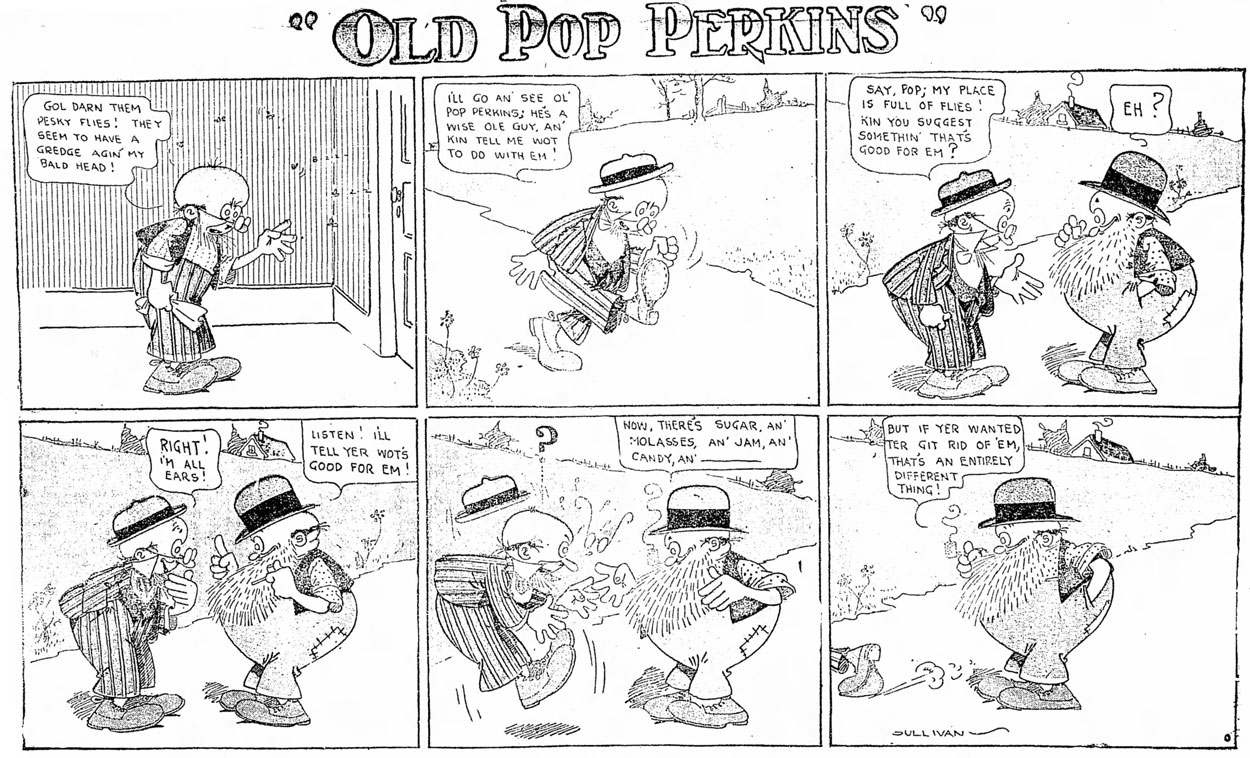

'Old Pop Perkins' from The Courier Journal (12 July 1914).

In early 1910, Sullivan arrived in New York City, where he initially made a living designing cinema posters and working as a prize money boxer. In the following year, he worked for the McClure Syndicate as an assistant to William Marriner on 'Sambo and his Funny Noises', a comic strip with a stereotypically portrayed black boy, based on Helen Bannerman's popular children's book series 'Little Black Sambo'. While ethnic comedy wasn't unusual for early 20th-century Western humorists, Sullivan is reported to have had actual racist opinions. According to one of his later animators, Rudy Zamora, Sullivan specifically rejected black applicants.

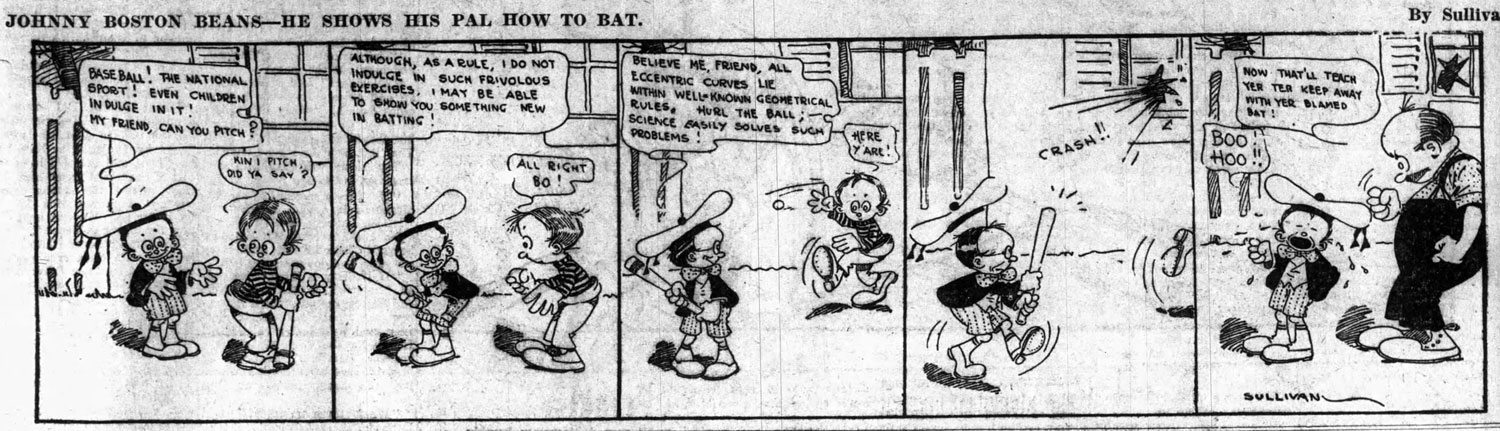

During this period, Sullivan also created some Marriner-inspired strips on his own, both for McClure and the New York Evening World. These included 'Great-Idea Jerry' (17 July 1912 - 5 April 1913), 'Johnny Boston Beans' (27 January-29 June 1914, copied from Marriner's 'Johnnie Bostonbeans' strip), 'Obliging Oliver' (11 May 1913-5 April 1914) and 'Old Pop Perkins' (22 March 1914-1915?). Some sources also mention a comic titled 'Willing Waldo'. After Marriner's death in October 1914, Sullivan left the syndicate and the field of newspaper comics.

'Johnny Boston Beans' (The Buffalo Times, 4 October 1914).

Early animation career

In October 1914, Sullivan joined the animation studio of Raoul Barré. Nine months later, he was fired because of unsatisfactory work. Sullivan was lucky that newspaper tycoon William Randolph Hearst set up his own animation studio, International Film Service, and bought away as many of Barré's employees as he could. At Hearst, Sullivan worked on several cartoons based on popular comic features from the Hearst papers. However, the animated shorts did little to please fans of the original comics, nor attract new ones.

Sullivan Studios

In 1916, Pat Sullivan established his own Sullivan Studios. One of the company's first projects was an animated version of William Marriner's newspaper comic 'Sambo', though retitled as 'Sammy Johnsin' to avoid copyright issues. This was followed by an animated series based on the popular Hollywood comedian Charlie Chaplin. Among the people he hired was the cartoonist Otto Messmer, who played an important role in Sullivan's future projects. Among the other staff were George Cannata, Al Eugster, Gerry Geronimi, Burt Gillett, Bill Nolan, Dana Parker, Hal Walker and Rudy Zamora.

However, in 1917 Sullivan was arrested and convicted for raping a 14-year old girl. He was sentenced to nine months and three days of prison, bringing his studio's productions to a temporary halt. While he was out on bail, he married a woman in the municipal building of Manhattan. She wrote to the Justice Department, pleading for leniency. During his imprisonment, Sullivan kept cartooning on postcards and envelopes he sent to his lawyer. After serving his time, Sullivan put his studio back in business.

Felix the Cat

On 9 November 1919, the Sullivan Studios debuted a worldwide commercial hit with the creation of the cartoon series 'Felix the Cat'. His shorts took advantage of all the possibilities of the still-young medium. The black cat often used, for instance, imagery from the scenery of his cartoons. Speaking in word balloons that appeared on screen, he would take out the words, punctuations, even the balloons themselves, or parts of his own anatomy if he needed them. This led to very funny, creative and often surreal moments. The feline also frequently broke the fourth wall. While Winsor McCay's 'Gertie the Dinosaur' (1914) was the first cartoon to revolve completely around the personality of one character and J.R. Bray's 'Colonel Heeza Liar' (1913-1924) was the first animated series overall, Felix was the first animated superstar. At the time, only 'Koko the Clown' by the Fleischer Studios rivalled him in popularity and inventiveness.

Throughout the 1920s, Felix was as recognizable as any live-action Hollywood star, and became the first animated character marketed with mass merchandising. Various sources have claimed that on 24 November 1932 Felix was the first comic character to be made into a giant balloon carried around during Macy's Thanksgiving Parade. In reality, that honor should go to Rudolph Dirks' 'The Katzenjammer Kids', who made their first appearance during the 6th edition, held on 28 November 1929. Taking into account the obscure 1915-1919 Katzenjammer Kids animated shorts made by International Film Service, Felix also can't hold the honor of being the first character from an animated cartoon series in the parade.

Nevertheless, his popularity was an unprecedented phenomenon. Ed E. Bryant and Hubert W. David wrote a song about the cat, 'Felix Kept On Walking' (1923), which was covered by various musicians, including jazz legend Paul Whiteman. In 1924, Bryant and David followed up with another song, 'Here He Is Again (Being More Adventures of Felix)'. Other music inspired by Felix from the same period were the songs 'Let's All Follow Felix (That Dog-Gone Crazy Cat)' (1923) by Ralph Stanley and Leslie Alleyn, 'Fido Followed Felix' (1924) by Harry Tilsey and 'Felix! Felix! Felix the Cat!' (1928) by Alfred Bryan, Pete Wendling and Max Kortlander. Even famed composer Paul Hindemith wrote an entire score for the now lost cartoon 'Frolics at the Circus' (1920).

When Charles Lindbergh made his famous non-stop flight across the Atlantic Ocean in 1927, he took a Felix the Cat doll along with him (after arriving in Paris he was given another doll, modeled after Émile-Joseph Pinchon's 'Bécassine'). During the experimental TV broadcasts by NBC in 1928, people tested the transmission by filming a Felix the Cat doll. The cartoons were not only popular with the general public, but also drew praise from Hollywood legend Charlie Chaplin and intellectuals such as French literary critic Marcel Brion and British novelist Aldous Huxley (of 'Brave New World' fame), who wrote: "Felix the Cat proves that what the cinema can do better than literature or the spoken drama is to be fantastic." Huxley also argued that European Expressionist filmmakers ought to take notice of Felix in order to avoid the pretentiousness and humorlessness that marred their work.

Felix the Cat: newspaper comics

After J.R. Bray's 'Colonel Heeza Liar' in 1916, Felix was the first animated character to be adapted into a comic strip, distributed between 1923 and 1967 by King Features Syndicate. It debuted as a Sunday comic in the British newspaper The Daily Sketch before it was published in the United States on 19 August 1923. Until its conclusion in September 1943, Sullivan's co-worker Otto Messmer was the main author of the 'Felix the Cat' Sunday feature, with Sullivan himself credited as the inker of the early episodes. On 9 May 1927, 'Felix the Cat' became a daily comic too, initially consisting of cut-and-paste reworkings of the cartoons by animator Jack Bogle. After 1931, Messmer started writing and drawing original stories for the daily strip, and continued to do so after the Sunday comic was cancelled. Another animator, Joe Oriolo, took over from Messmer from 1954 until the strip's cancellation in January 1967. Other artists who worked on the 'Felix the Cat' newspaper comics were Bill Holman, Dana Parker and Ed Cronin.

Right from the start, the 'Felix the Cat' Sunday page was accompanied by topper comics, like 'Laura' (1926-1935), 'Funny Films' (1933-1935), 'Sunny Side' (1935), 'Bobby Dazzler' (1935-1940), 'Gus the Ghost' (1940) and 'Don Poco' (1940-1942). 'Laura' centered on the antics of a talkative parrot. The 'Bobby Dazzler' strip also appeared as 'Bobby and Chip' (1936-1938) in the British Mickey Mouse Weekly. These were in turn reprinted in Mickey Mouse Magazine, the first full-scale US periodical devoted to Walt Disney's iconic mouse, published by Hal Horne and later Kay Kamen.

Felix the Cat: comic books

Between 1948 and 1955, the first series of monthly 'Felix the Cat' comic books was published by Dell Comics and Toby Press. In the 1990s, Harvey Comics also published 'Felix the Cat' comics, scripted by Jack Mendelsohn and drawn by Frank Hill, among other people. During the 1990s and 2000s, the American imprint Felix Comics released a new line of 'Felix the Cat' comics, including the series 'Felix the Cat and Friends' (1992-1993), 'The New Adventures of Felix the Cat' (1992-1993) and 'Felix the Cat in Black and White' (1997-1999), as well as a great many one-shot books. Among the writers and artists involved were Don Oriolo, Scott McRae, Dan Parent, Robert Wetterauw Jr., Jenn Henning, Pete Fitzgerald and Jean Caliguire.

Felix the Cat: international comics

Until well into the 21st century, locally produced 'Felix the Cat' comics appeared in other countries, some unofficial, others licensed. Between 1926 and 1928, the British comic artists Charlie Pease and Arthur Martin also had a humor comic strip named 'Felix the Fat', which, apart from the lame pun in the title, had nothing to do with Sullivan's Felix. The Italian cartoonist Guglielmo Guastaveglia teamed up Sullivan's 'Felix the Cat' with Walt Disney's 'Mickey Mouse' for a series of illegal 'Topolino' strips in the newspaper Il Popolo di Roma (1928). From the 1950s through the 1990s, local comic book stories with 'Felix the Cat' was produced by the Italian publishing houses Edizioni Bianconi and Editoriale Metro, with artists like Tiberio Colantuoni, Sandro Dossi, Umberto Manfrin, Alberico Motta, Pierluigi Sangalli and Mario Sbattella.

In East-Germany, the original 'Felix the Cat' comic strip in the Leipziger Volkszeitung was succeeded by standalone episodes of a so-called "DDR-Felix", drawn by local artist Joachim Nusser. Between 1958 and 1981, the West-German publisher Bastei Verlag published a weekly Felix magazine, with locally produced comic stories by Spanish artists of Studio Ortega, like Alfonso Borillo, Ignasi Calvet Esteban and Juan Alonso Villanueva, as well as the German Atelier Reindl Dachsel.

'Laura' Sunday topper, credited to Sullivan, but ghosted by Messmer.

Final years and death

Eventually the success of 'Felix the Cat' became too much for Sullivan. He was an alcoholic and often drank during working hours. Several employees, including Otto Messmer, Shamus Culhane, George Cannata and Al Eugster, remembered that their boss was never sober. During his drunken rants, he sometimes fired people on the spot. However, nobody took this seriously, because the next day he didn't remember his behavior from the previous day. A downside of Sullivan's drinking problem was that the studio didn't adapt to the changing times. By the late 1920s and early 1930s, he refused to make the transition to sound and color cartoons, which put 'Felix the Cat' at a major disadvantage, especially compared with the tremendous success of the Walt Disney Studios and their star Mickey Mouse (who was largely modelled after Felix).

In 1932, Sullivan's wife Marjorie accidentally leaned too far from an open window and fell to her death, seven stories below. The couple already had an unhappy marriage, with Sullivan being diagnosed with syphilis and mental decline. Still, he unavoidably drowned his sorrows in alcohol. Almost a year later, Sullivan passed away too, in his case from alcohol-induced pneumonia. He left no testament or any book-keeping records behind. As a result of his careless management, the Sullivan Studios were forced to close down, bringing the 'Felix the Cat' series to a sudden end.

'Felix the Cat'.

Creator controversy

After Sullivan's death, his main animator and comic artist Otto Messmer claimed that he was Felix' rightful creator. But he never received any official credit, nor a dime of the royalties. Many of Messmer's colleagues also acknowledged that Sullivan was hardly present - or sober for that matter - in the studio after 1925, while the rest of his staff kept all production running. His posthumous reputation as an alcoholic, racist, convicted rapist and disastrous business manager didn't make him more sympathetic in the eyes of people who stand with Messmer.

Still, all of Sullivan's vices should be separated from the basic question whether he or Messmer was Felix' creator. As early as 1917, Sullivan directed an animated short called 'The Tail of Thomas Kat', featuring a prototypical black cat. Messmer's design for Felix in the short 'Feline Follies' (1919) was very reminiscent, down to the original name for the cat, "Master Tom". Only after his third cartoon did Felix finally receive his current name. Sullivan claimed he named Felix after the word "Australia Felix" ("Lucky Australia"), a term used by 19th-century explorer Thomas Mitchell. Messmer on the other hand pointed at his colleague John King, who named the cat after the Latin word "felix" ("lucky"), which also was very similar to the Latin word "felis" ("cat"). Messmer claimed that he was the sole author of the cartoon 'Feline Follies' (1919), which several animation historians have backed up. Defenders of Sullivan point out that Sullivan's handwriting can be seen throughout the short. Around the four minute mark, a speech bubble appears in the left corner of the screen, which reads "Mum". Australians like Sullivan would spell the word for "mother" as "mum" while Americans like Messmer would spell it as "mom".

The issue about Felix' creation will probably never be solved. It cannot be denied that Messmer was largely responsible for the development of Felix' personality. He drew the character more often than Sullivan ever did, both as an animator and as a comic artist. But Sullivan's business sense played an equal part in Felix' enduring success. Even taken in regard that he possibly merely laid the foundations, this is still a tremendous feat for a medium that was still in its infancy in 1919.

The controversy about who the real creator of 'Felix the Cat' somewhat repeated itself about a decade later with Mickey Mouse. For decades, Walt Disney was credited with the creation of Mickey, while today even the Walt Disney Company acknowledges the role of animator Ub Iwerks in Mickey's creation. A similar dispute is the debate who is the real creator of Bugs Bunny, with people arguing whether Tex Avery, animator Bugs Hardaway or Bob Clampett deserves the most credit. History repeated itself again when both Seymour Reit and Joe Oriolo claimed to be the sole creator of Casper the Friendly Ghost. In another situation, Alex Anderson took legal action to make it clear that he was the real creator of 'Rocky & Bullwinkle', and not Jay Ward. In 1996, the 'Felix' controversy was satirized in Matt Groening's cartoon show 'The Simpsons', namely in the episode 'The Day the Violence Died', where it is argued who was the original creator of Itchy from the fictional 'Itchy & Scratchy' series.

Legacy and influence

Despite being over a hundred years old, 'Felix the Cat' remains an icon of animated history. He can be considered the godfather of all cartoon stars and inspired numerous animators and cartoonists, including Walt Disney, Ub Iwerks, Paul Terry, Bob Clampett, Raoul Servais, Sally Cruikshank, Bjorn Frank Jensen, Tabaré, John Kricfalusi, Bruce Petty and Matt Groening. Disney and Ub Iwerks modeled Julius the Cat (from their 'Alice Comedies'), Oswald the Lucky Rabbit and Mickey Mouse after Felix. At Paul Terry's Terrytoons Studio's, Waffles the Cat was also a direct copy. Japanese manga artist Suiho Tagawa's black-and-white dog Norakuro was based on Felix too. While Felix' name refers to "luck", the word "norakuro" is an abbreviation of "noranu" ("stray dog") and "kurokichi" ("black luck").

In 1936, Felix was briefly revived as a cartoon star by the Van Beuren Studios, but failed to appeal to a new audience. The character was revived during the early years of TV as the star of the children's series 'Felix the Cat' (1959-1961), produced by Felix the Cat Productions and distributed by Trans-Lux. The show gave Felix a magical bag and introduced a new cast of side characters, including his nemesis The Professor and his sidekick Poindexter. It also had a memorable theme song, sung by Ann Bennett and composed by Winston Sharples. Both Joseph Oriolo and Pat Sullivan's son Pat Sullivan Jr. were closely involved in the production. In 1970, Oriolo obtained the rights to Felix. Between 1984 and 1988, Brian, Greg, Morgan and Neal Walker created a newspaper comic, 'Betty Boop and Felix', teaming Felix up with Max Fleischer's Betty Boop, only to find out later that they didn't own the rights to Felix, so they quickly made it a Betty-centered comic instead.

In 1989, 'Felix the Cat' appeared in his first full-length animated feature film, 'Felix the Cat: The Movie' (1989), co-produced by Animation Film Cologne and Pannónia Filmstúdió and directed by Tibor Hernádi. However, the picture was a critical and financial box office flop. A reboot of the 'Felix the Cat' TV series was produced by Film Roman as 'The Twisted Tales of Felix the Cat' (1995-1997), with Joe Murray as a character designer. It was broadcast on CBS. A short-lived junior spin-off of 'Felix the Cat', titled 'Baby Felix' (2000-2001), ran on the Japanese TV network NHK. Contrary to older cartoon characters, Felix is still used in merchandising today and remains recognizable to anyone with even a mild interest in animation.

In Norman Rockwell's illustration 'Boy In a Diner' (1946), a boy is portrayed with a 'Felix the Cat' comic book sticking out of his pocket. In France, 'Felix the Cat' comics were spoofed as a sex parody by Roger Brunel in 'Pastiches 2' (1982). In the 1990s, house DJ Felix Stallings, Jr. adapted the stage name Felix da Housecat.