Rodolphe Töpffer was a 19th-century Swiss cartoonist, generally regarded as the "inventor" of the comic strip. While many of his techniques had already been used by artists centuries earlier, Töpffer brought them together to develop what we nowadays recognize as comic stories, with text and drawings so intertwined that they cannot be understood without each other. Töpffer created original fictional characters and used them in long, humorous narratives. The length allowed for both serialization in magazines and book releases. His classic stories 'Mr. Jabot' (1833), 'Mr. Crépin' (1837), 'Mr. Vieuxbois' (1837), 'Mr. Pencil' (1840), 'Mr. Cryptogame' (1845), 'Albert' (1845) and 'Dr. Festus' (1846) were widely translated and reprinted bestsellers. They not only launched a market for this new medium, but also inspired many other artists. Numerous cartoonists imitated or even plagiarized him. In that regard, Rodolphe Töpffer was the most influential comic artist of the early 19th century, whose impact continued to resonate even decades later. Apart from his historical importance, Töpffer's work also shows artistic depth. His stories are funny, imaginative, well written and have a satirical edge. Together with David Hess, Rodolphe Töpffer is the first known Swiss comic artist who can be identified by signature. He was also the first cartoonist to write a book about his comics. Even two centuries later, Töpffer's legacy is still held in high regard by comic historians and fans.

Early life and career

Rodolphe Töpffer born in 1799 as the son of painter Wolfgang Adam Töpffer, a German immigrant who had settled in Geneva, Switzerland. Töpffer's father was a caricaturist who gave drawing lessons to Joséphine de Beauharnais, the first wife of Napoleon Bonaparte. During his travels, he visited England and brought back some cartoon books. Rodolphe Töpffer cited two specific picture stories as direct inspirations for his own comics. The first was William Hogarth's 'Industry and Idleness' (1747), a morality tale about the benefits of hard work, told in sequential engravings. The other was William Combe's novel series 'Dr. Syntax' (1812-1821), illustrated by Thomas Rowlandson. In a letter written to his cousin and publisher Jacques-Julien Dubochet, it is also confirmed that Töpffer was aware of the work of J.J. Grandville.

Between 1819 and 1820, Rodolphe Töpffer studied in Paris, after which he returned to Geneva to become a school teacher in Latin, Greek and ancient literature. He got married in 1823 and had four children, two girls and two boys. Two years later, he used his bridal fortune to found his own boarding school for boys in Geneva. Töpffer was strongly influenced by Jean-Jacques Rousseau's pedagogical theories, and organized excursions and study trips in Switzerland, Italy and France. Starting in 1825, he also published his accounts in book form. Each volume discussed a specific voyage, complete with personal illustrations. In 1843, they were compiled into one book, 'Voyages en Zig-Zag' (1843). In 1832, Töpffer was named a Professor of Rhetoric at the Academy of Geneva (nowadays the University of Geneva). He was also active in the provincial parliament for Geneva, representing the Conservative Party.

In his spare time, Töpffer wrote short stories ('La Bibliothèque de Mon Oncle' [1832], 'Le Presbytère' [1832]), novels ('Rosa et Gertrude', 1847), plays ('L'Artiste', 1829) and essays about art ('Essai sur le Beau dans les Arts, 1848). In 2004, his stage play 'Quiproquo' was performed with set and costume designs by cartoonist Gérald Poussin. Apart from this rare revival, most of Töpffer's literary output is nowadays forgotten, with a notable exception for his comics.

Comics

Between 1827 and 1833, Töpffer created six picture stories: 'Les Amours de Mr. Vieux Bois' (1827), 'Docteur Festus' (1829), 'Histoire de M. Cryptogame' (1830), 'Monsieur Trictrac' (1830), 'Histoire de Monsieur Jabot' (1831) and 'Monsieur Pencil' (1831). He called them "histoires en images" ("stories in images") or "littérature en estampes" ("graphic literature"). Since he was a respected pedagogue and teacher, Töpffer originally didn't consider making these stories public. He purely wrote and drew them for his own amusement and the entertainment of his friends.

It took a man of great literary stature to convince Töpffer otherwise. The legendary German writer, poet and playwright Johann Wolfgang von Goethe loved Töpffer's 'Dr. Festus', whose name was slightly based on Goethe's own masterpiece 'Faust'. In a letter, dated 4 January 1831, Goethe praised Töpffer as somebody who "sparkled with talent and spirit: 'Some of his pages cannot be surpassed (...) Töpffer seems to stand on his own legs and is the only talent I can think of who is so original.'" Though even Goethe couldn't resist adding: "If he would pick out a less frivolous topic in the future and get his act more together, he would do things which surpass all concepts." The author also liked the manuscript of 'Mr. Jabot'. Goethe's praise is particularly notable, given that the author had a strong dislike for caricatural cartoons. Unfortunately, Goethe passed away in 1832, before Töpffer's first picture story was published.

Töpffer's picture stories received some notability when he released them as lithographed book publications, distributed with the help of publisher Abraham Cherbuliez. However, Töpffer didn't have his picture stories released in chronological order, and often redrew them for these official publications. In 1833, he picked out 'Histoire de Mr. Jabot' for his first book, although it was actually the fifth story he created. As a credit, Töpffer modestly used his initials "R.T.", but once his books became more popular, he began using his full name. 1837 saw the publication of the very first comic he ever created, 'Les Amours de M. Vieux Bois', as well as a brand new story, 'Monsieur Crépin' (1837). In 1840, Töpffer released 'Docteur Festus' and 'Monsieur Pencil' in book format. Just like the 1837 story 'Monsieur Crépin', the 1845 tale 'Histoire d'Albert' was a rare Töpffer story released directly after its creation. Töpffer's third picture story, 'Histoire de Mr. Cryptogame' (1830), received new woodcut engravings by Cham for its 1845 serialization in L'Illustration, the magazine published in Paris by Töpffer's cousin Jacques-Julien Dubochet. A book release followed in 1846.

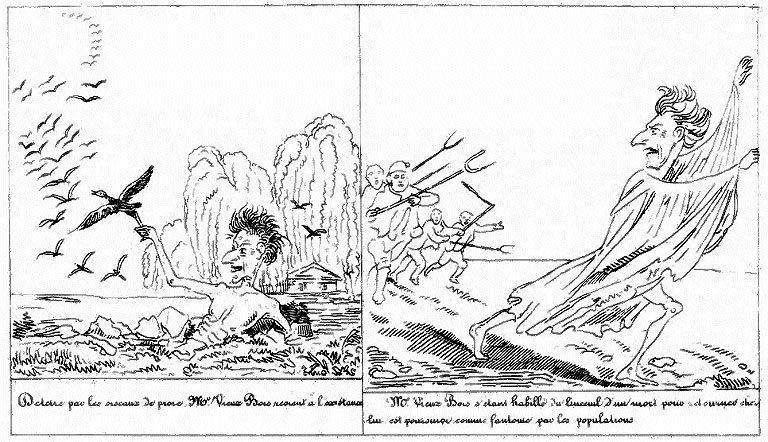

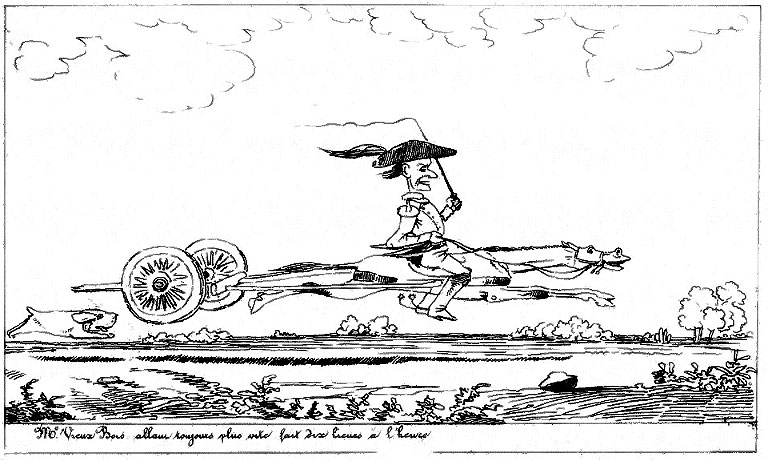

'Les Amours de Mr. Vieux Bois'.

M. Vieux Bois

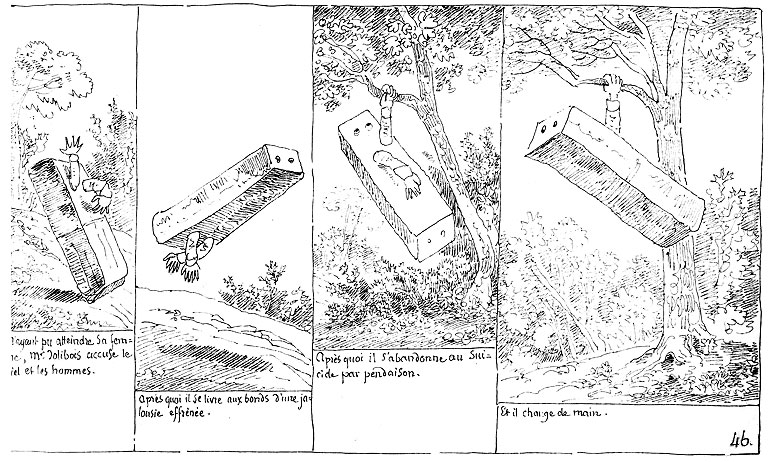

The first comic story that Töpffer made was 'Histoire de Mr. Vieux Bois', also known as 'Les Amours de M. Vieux Bois' ("The Loves of Mr. Vieux Bois", 1827). Although chronologically the first, it appeared in print as his third published story. Like the title implies, it centers on the turbulent romances of Mr. Vieux Bois, a naïve, melodramatic man with a desperate crush on a young woman. By defeating her suitor in a duel, he wins her hand in marriage. Nevertheless, he has to overcome a lot of obstacles before the couple can finally be together. Overcome by desperation, the poor mister Vieux Bois undertakes several suicide attempts over the course of the story.

His tribulations have him get imprisoned several times, end up in a monastery, being robbed of his clothes and presumed dead and buried. Crawling out of his grave, he scares the townspeople who think he is a ghost, after which he is imprisoned. When he finally rejoins his lover, they run off by coach. During the trip, the carriage falls off the coach, with his sweetheart inside. She is rescued by her original suitor and he and Vieux Bois have a final confrontation over her hand. Although she chooses Vieux Bois in the end, their troubles are still not over. A group of monks that Vieux Bois has encountered earlier in the story try to burn the couple at the stake. After yet another successful escape, Vieux Bois and his loved one finally get married.

In 1837, a decade after its creation, 'Les Amours de M. Vieux Bois' first saw print. Nevertheless, it became Töpffer's best-known and most translated comic book. In 1841, the English-language version, 'The Adventures of Mr. Obadiah Oldbuck' (Tilt & Bogue, London), came out, with a title page design by George Cruikshank. However, this translation was based on an inferior 1839 bootleg copy, published by Gabriel Aubert. Most of the imagery was redrawn by an anonymous artist and printed in reverse, which confused readers. When Töpffer found out, he sent Tilt & Bogue the original copies and had them released instead. On 14 September 1842, the New York weekly magazine Brother Jonathan printed 'Obadiah Oldbuck' in a special supplement. The U.S. book version was published by John Neal, which makes it the earliest known comic book published on U.S. soil. The first U.S. comic book made by American citizens had to wait until James & Donald Read published 'Jeremiah Saddlebags' (May 1849). By 1849, 'Obadiah Oldbuck' was popular enough in the USA to be reprinted (with Töpffer's original art intact) as 'The Adventures of Mr. Obadiah Oldbuck' (Wilson & Co, New York). In 1921, the story was also adapted into an animated short by Robert Lortac.

'Les Amours de Mr. Vieux Bois'. English-language version.

Dr. Festus

Töpffer's second story, 'Le Docteur Festus', was written and drawn in 1829, but only published in 1846. The title pays homage to both Thomas Rowlandson's 'Dr. Syntax' (1809-1812) and the 1808 Goethe novel 'Dr. Faust'. The tale is driven by Dr. Festus' absent-minded mistake to walk into the wrong hotel bedroom and get locked inside the suitcase of a certain Milady. Two thieves steal the suitcase, but in the woods, Festus jumps out and scares them off. Still in his nightwear, he hides in a haywain. Meanwhile Milady has warned the police, who accidentally arrest her husband Milord, who was also robbed of his clothes by the thieves. Since he is stripped down to his night-gown they assume he is the suitcase thief. Milord later puts on the clothes of a major. This set-up is the start of a cataclysmic chain reaction of events, in which all the main characters are at one point mistaken for somebody else, with whoever wearing the major's clothes being blindly followed by a group of foolish soldiers.

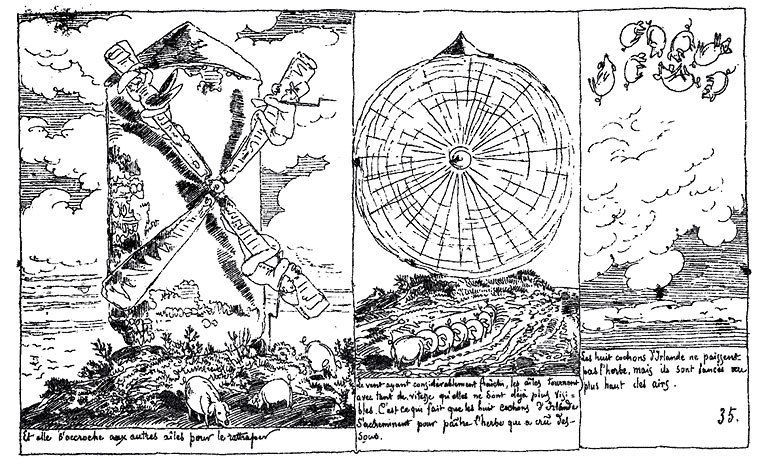

'Dr. Festus' is a great farcical tale in which funny misunderstandings and absurd events flow perfectly into one another. For instance, when six pigs are launched in the air by windmill blades, they only plummet back to Earth three weeks later. By that time, the narrator explains, "there are 28 of them, because the sows have given birth to piglets." The story is also intercut with witty satirical commentary. After Festus caused mayhem in a mill, the millers contact the police, but by the time they arrive he has vanished. The officers scold the miller for letting them arrive for nothing. After they've gone, the miller beats his wife, while she beats their servant, who, at his turn, ventilates his frustrations on the donkey. Töpffer mocks the incompetent police force who always make the wrong deductions, while the blindly obedient and brainless soldiers are a theme he later revisited in 'Monsieur Pencil'. The astronomical world is ridiculed as well. A group of scientists all try to be the first to spot a "new comet", so they can name it after themselves. Many already "wear an eyepatch for staring too much at the zodiac". Several bicker over which of their hypothetical theories is the right one. In some reprints, censors cut the scene in which a committee misinterprets Milord and Milady's laundry list as a conspiracy to overthrow the monarchy. Editors feared lèse-majesté, particularly the moment when the royal couple faints upon hearing the committee's conclusions.

Mr. Crypogame

In 1830, Töpffer created 'Histoire de M. Cryptogame', about an obsessive butterfly collector and his fiancé, Elvire. Elvire dislikes her partner's hobby and forces him to sign and arrange their wedding. However, Cryptogame flees to the USA by ship. When it turns out Elvire has followed him, he jumps into the ocean. Elvire dives behind him, while the confused captain and crew do the same. Cryptogame is swallowed by a whale, but inside its belly he finds a beautiful woman more to his taste. He also meets a good friend - a doctor - and two missionaries, who help him conduct a wedding inside the sea mammal, whereby Cryptogame marries his young bride. After a wild party, the whale spits everybody out and the newlyweds are unwillingly separated. Cryptogame's bride is rescued by a Napolitan sailing ship, while Cryptogame and his doctor friend end up at the North Pole. Norwegian whalers pick up their frozen bodies. As it so happens, Elvire ends up on the same ship. After everybody is unfrozen, she reminds Cryptogame of his marriage promises. Cryptogame remains silent about his recent wedding, under the assumption that his bride is gone forever. When the Doctor wants to marry Elvire, Cryptogame encourages the idea. This is not to Elvire's liking and a huge fight-and-chase scene break out. Soon all passengers chase behind the trio, unaware of what is going on.

Meanwhile, a group of Algerian-Turkish pirates have hijacked their ship and sell all passengers into slavery. Cryptogame has to serve the Bey of Algeria, while the Doctor becomes a tutor to the monarch's children and Elvire joins his harem. She manages to murder the Bey, while the Doctor is tormented by the Bey's dysfunctional offspring and accidentally sets the palace on fire. After escaping, the trio takes the first ship back to Europe. On board, Cryptogame finds his bride back and rows off with her in a lifeboat. Elvire stalks them all the way to the island where Cryptogame and his wife go ashore. Her jealousy literally makes her explode. With Elvire out of the picture, Cryptogame and his true love can finally be happy together, although she already has eight children from a previous marriage.

It took 15 years before 'Histoire de Mr. Crytogame' was finally published. Between 25 January and 19 April 1845, it was serialized in the Parisian magazine L'Illustration. For this occasion, the artwork was redone with wood engravings by Cham. This time the English-language comic book publication, 'The Veritable History of Mr. Bachelor Butterfly' (Tilt & Bogue, July 1845), actually came out before the French one, which was published in October of that same year.

English edition of the redrawn version of 'M. Cryptogame' by Cham.

Mr. Crypogame - international versions

In 1847, the Swiss writer Julius Kell (1813-1849) translated 'Mr. Cryptogame' into German, but added numerous changes. With a children's audience in mind, he wrote the text in rhyme, a common practice in German juvenile literature at the time. Kell also censored several scenes and rearranged others in order to still have a coherent story. All instances of bigamy and adultery were removed. The marriage inside the whale was cut. The two missionaries inside the belly were turned into a farmer and his servant. Kell changed Cryptogame's name too, since it was a contraction of the Greek words "kryptos" ("hidden") and "gamos" ("marriage"). Instead, he named him Steckelbein, which literally translates to "prickly leg". Elvire was renamed Ursula and turned into Cryptogame's sister instead of his wife. In Kell's eyes, it made her obsession with Cryptogame's love life more innocent. Yet it also changed the victim's role, as her jealousy now feels completely unjustified and even unintentionally incestuous. The prudent censor also removed Elvire's murder of the Bey. Oddly enough, he did keep her own violent death. To modern-day audiences, Kell's changes not only feel disrespectful to the original author, but also misogynist. Töpffer never knew about this censored version, because he died a year before Julius Kell's 'Fahrten und Abenteuer des Herrn Steckelbein: Eine Wunderbare und Ergötzliche Historie' (F.A. Brockhaus & Avenarius, 1847), was published.

In the Netherlands, man of letters Jan Goeverneur (1809-1889) used Kell's German version for his Dutch translation, 'Reizen en Avonturen van Mijnheer Prikkebeen' (1858). 'Mijnheer Prikkebeen' became very popular in the Netherlands and was reprinted until deep into the 20th century. The 1943 reprint was reworked with new illustrations by Ben Mohr. Töpffer's translated story even received unofficial sequels. In 1909, the Dutchman Daniël Hoeksema drew 'De Neef van Prikkebeen' (Gebroeders Koster, 1909), about Cryptogame's nephew, Petrus Prikkebeen Jr. During the 1930s, Jac A. Hazelaar made 'Zoon van Prikkebeen', about the character's son. in 1938, Dutch artist Peter Lutz made another comic book about Prikkebeen's son, 'Avonturen van Prikkebeen Junior'. Scriptwriter Gabriël Smit and artist Aart van Ewijk drew another 'Prikkebeen'-based story, 'De Wonderlijke Avonturen van Mijnheer Prikkbeen' (1940-1941), serialized in local papers like De Gooi en Eemlander & Nieuwsblad van het Noorden, with a book publication afterwards by Het Spectrum.

Cryptogame's fame in the Netherlands was such that it inspired no less than two hit songs, namely Boudewijn de Groot's 'Meester Prikkebeen' (1968) and Rob de Nijs' 'Zuster Ursula' (1973), both based on the Dutch character names from the comic. Bob Vrieling also recorded a song titled 'Prikkebeen' (1970), which spent only a week in the charts. In 1972, the comic inspired the Dutch TV series 'De Avonturen van Meneer Prikkebeen', which combined live-action with animation and was produced by Harrie Geelen. In 2011, Peter-Jan Wagemans composed an opera based on Prikkebeen, titled 'Legende: De Ontsporing van Meneer Prikkebeen' (2011).

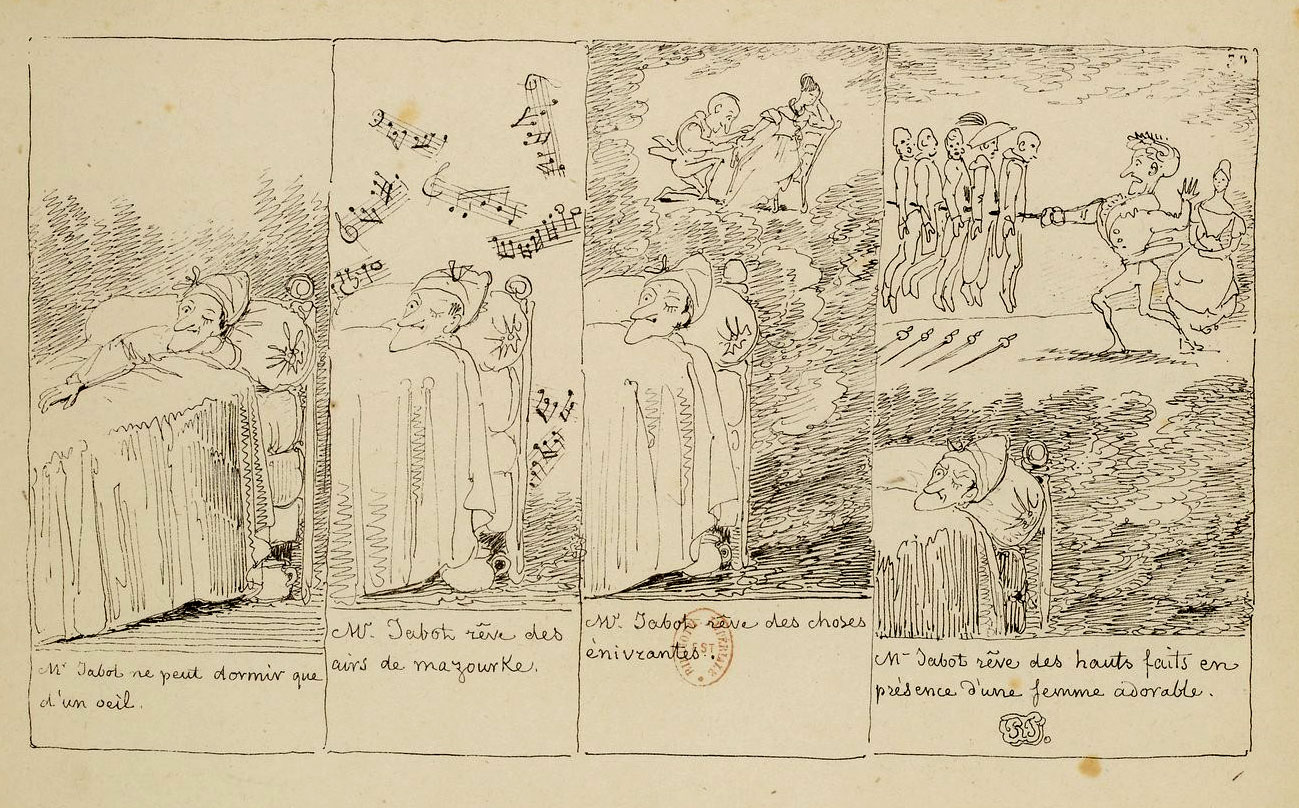

Mr. Jabot

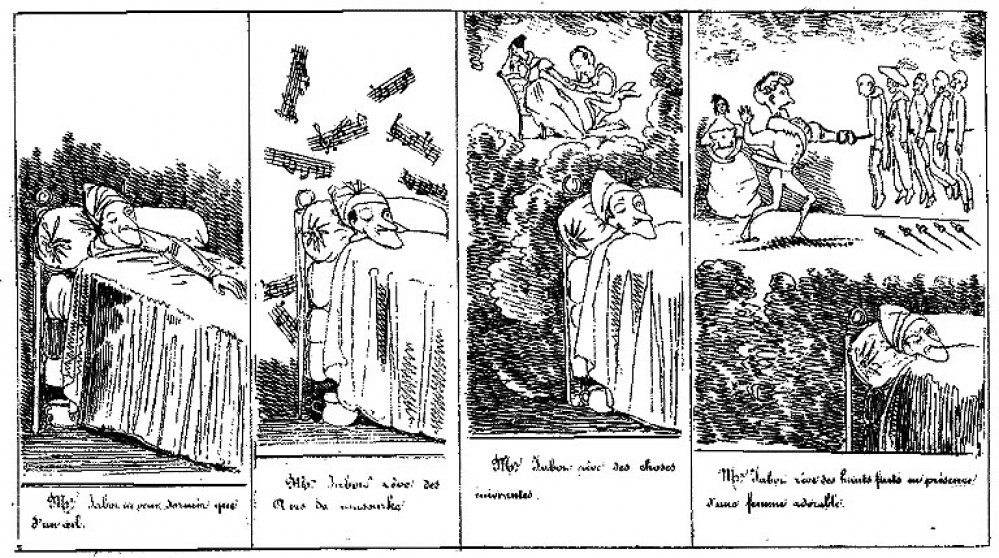

Between 29 January and 5 February 1831, Töpffer wrote and drew 'Histoire de Monsieur Jabot', a funny satire of high society. The plot was slightly based on Molière's classic comedic play 'Le Bourgeois Gentilhomme' (1670). Just like Mr. Jourdain, the main character in Molière's play, Töpffer's protagonist Mr. Jabot fancies himself a person of high class and expertise. The first act is set at a ball. Jabot is so status-obsessed that he avoids people of lower rank. Even when his cousin turns up - a socks salesman - Jabot pretends he doesn't know him. The upper class twit is so obnoxious that he blames others for his own mistakes. By the end of the night, Jabot has made himself very unpopular. But he still goes home thinking he made a great impression. He even dreams about his wonderful future.

The next day, Jabot has a duel with one of the people he quarreled with the night before. Rather than shoot his opponent, Jabot simply fires in the air. This generous deed helps him clear his differences. Later that night, Jabot returns to his apartment, where his candle accidentally sets his nightgown on fire. A series of comical misunderstandings takes place, with a woman in the opposing room misinterpreting the sounds Jabot makes. She - the marchioness de Mirliflor - for instance thinks Jabot committed suicide, but in reality, his gunpowder simply exploded because of the flames. While the marchioness and Jabot are asleep, Jabot's hunting dogs accidentally push their separate beds together in the same room. In the pitch dark room, she mistakes Jabot for a burglar. After she cries for help, the hotel owner storms in, but Jabot thinks he is the burglar and throws him out the window. Thankful that he saved her life, Jabot and the marchioness marry the next day.

Chronologically, 'Histoire de Mr. Jabot' was the second picture story Töpffer wrote, but the first to appear in print. In 1833, the Geneva-based printer Caillet and the publisher Cherbuliez released it in book format. In 1839, the tale was serialized in the French satirical magazine Le Charivari, but clumsily redrawn by another artist, much to Töpffer's dismay. To add insult to injury, Le Charivari's publishing company Aubert brought out this butchered version in book format. And as if that wasn't enough, the first English translation, 'The Comical Adventures of Beau Ogleby', used Aubert's bootleg. It was serialized in Gentleman's magazine, after which Tilt and Bogue published it in book form in 1842. None of the editors had any clue that they had translated a redrawn copy. They simply took the badly copied drawings and mistakenly mirrored images for granted. When Töpffer found out, he instantly sent Tilt and Bogue the real version of 'Mr. Jabot' and had them reprint it. In 1860, Les Garnier Frères in Paris published yet another redrawn version of the same book. The artist tasked with redrawing all the images was François Töpffer (1830-1870), the creator's own son. This version was reprinted in 1975 by Horay.

Monsieur Pencil

In 1831, Töpffer wrote and drew 'Monsieur Pencil', which was first published in 1840. The story revolves around three people who are all picked up by a gust of strong wind and dropped in unwanted locations. Like in Tópffer's previous stories, the book follows an over-the-top narrative full of crazy coincidences and misunderstandings. A bourgeois man is catapulted on a sailboat, on which a Mr. and Mrs. Jolibois are just crossing the river. The wind then lifts all three people back in the air. Mrs. Jolibois' shoes and umbrella fall into the garden of a doctor, who thinks the end of the world is near. When Mr. Jolibois crashes on his lawn, the doctor thinks he's an extraterrestrial creature and locks him up. Later, Mrs. Jolibois also lands on the doctor's house, though more softly since her crinoline dress functions as a parachute. Her husband isn't happy to see her, because he thinks she had an affair with the bourgeois. As he starts beating her, a servant locks him up.

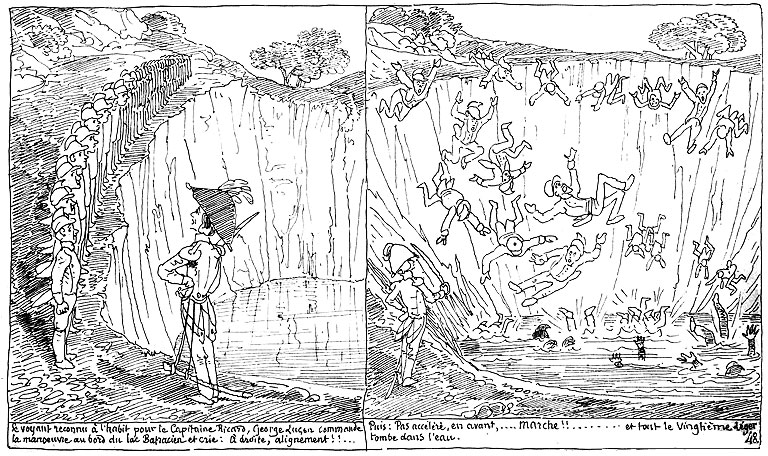

At that same moment, the bourgeois falls into a haywain. Mrs Jolibois, on the run from her husband, bumps back into him. Coincidentally, the wind throws the painter Mr. Pencil into the same haywain. Farmers bring the hay to a farm, where the trio steals horses and escapes. The animals are retrieved by a man named George Luçon, who is later accused of horse theft and sentenced to execution. Luckily, the firing squad is so incompetent that they accidentally hit their captain. Luçon steals his uniform and flees. Meanwhile, Mr. Jolibois is locked inside a coffin and sent to the academy by carriage for further analysis. The coffin gets lost in the woods, where Pencil, Mrs. Jolibois and the bourgeois find it. When Mr. Jolibois recognizes them, he tries to attack them, but all he can do is stick his hands through two holes in the coffin and crawl over the ground. He scares off Luçon, who thinks he's a monster. Luçon then stumbles upon a group of soldiers. Since he still carries the captain's uniform, they think he's their officer. Luçon commands them to walk off a cliff, which the obedient idiots do.

Meanwhile, mass panic has broken out. The doctor claims an extraterrestrial invasion has broken out. Other people fear a cholera outbreak, while others assume the "Beast of Gévaudan" has returned (a legendary 18th-century giant wolf). Armies are mobilized, the economy collapses and politicians argue about the correct measures to take. The doctor and his maid eventually find Jolibois back in his coffin. They take him to a nearby village, where the locals steam the coffin above a fire to disinfect it against cholera. Roasting inside, Mr. Jolibois is overheated with anger once he gets out. He attacks the doctor, but his maid fights back. At that precise moment, Mr. Pencil and Mrs. Jolibois enter the room, making her think that her husband has run off with the maid. Eventually, all misunderstandings are cleared up and peace returns to the country.

'Mr. Pencil' has some of Töpffer's funniest satire of blind belief. The soldiers are so stupid that they obey anybody in uniform, even if it costs them their lives. The doctor follows assumptions, rather than thinking rationally. Purely because of his social status, everybody believes his story about an extraterrestrial invasion. The government wastes time thinking up a solution, while the working class reminds them of an actual crisis, namely famine. The only people who are delighted with the cholera epidemic are "morticians and chemists". During the time Töpffer wrote this story, parts of Western Europe were indeed ravaged by a cholera outbreak.

'Histoire de M. Crépin'.

Mr. Crépin

In 1837, Töpffer wrote and drew 'Histoire de M. Crépin'. The main character has 11 children. Since his kids are so numerous and busy, he decides to hire a tutor. Several candidates apply for the job, all with different pedagogic theories. As a running gag, Crépin's wife always understands the theories, or is at least gullible enough to accept them. Crépin, on the other hand, is more skeptical, since he fails to see any positive change in his offspring's behavior. The first tutor is more preoccupied with theory than practice. When Crépin confronts him that he's nothing but talk, an argument breaks out. The disgruntled teacher is chased outside by Crépin's children, but he hurls bricks at the windows in revenge. He causes a scene, which brings out a crowd and police interference. Only when Crépin's dogs attack the tutor, he finally runs away.

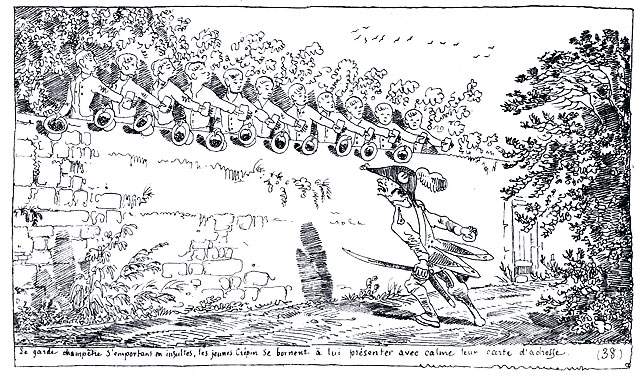

Since Mr. and Mrs. Crépin can't decide between the next two tutors, they hire both at once. His choice, Mr. Bonichon, wants the youngest children to study physics. Her choice, Mr. Fadet, teaches the oldest children about fractal numbers. In the end, the kids make a mess out of the kitchen and scribble the walls with math sums. After a huge argument over the value of his educational methods, Bonichon leaves to become an assistant customs officer. Fadet stays behind and manages to make the children well-mannered and obedient. They react to everything in polite unison. However, after insulting a policeman, their hats are confiscated and Crépin has to pay a fine, after which the children instantly return to their previous bad behavior. Crépin blames Fadet, who is sent off to jail. The disgraced teacher manages to escape by starving himself, so he can climb through the prison bars. Crépin has no hard feelings and rehires him as his accountant.

Through a series of misunderstandings a phrenologist, Mr. Craniose, visits Crépin's mansion. In the 19th century, the idea that somebody's skull could determine delinquent behavior was widespread and Töpffer mocks this mercilessly. Craniose concludes that Crépin's children have "bad skulls" and are therefore destined to become "bad and stupid people". Crépin instantly throws him out, while his children use Craniose's skulls as bowling balls. The story then wanders off into a subplot, built around Craniose's adventures in Belgium. He buys a new collection of skulls from a gravedigger in the Dutch town Bergen op Zoom and gives a show in Brussels. In the end, Crépin sends his children to the Bonnefoi boarding school. After teachers send letters of complaint, the couple again argues whether they made the right choice. Crépin's wife feels that the previous tutors at least used methods she understood. But in the end, Crépin's children all graduate cum laude and have lucrative careers. The tutors, on the other hand, all die miserable deaths.

'Histoire de Mr. Crépin' was a story close to Töpffer's heart. As a pedagogue, he had very outspoken ideas on how children should be raised. In the story he satirizes various teaching methods, along with once prevalent phrenological theories. Töpffer strongly favored Jean-Jacques Rousseau's theories and disliked those of fellow Swiss Johann-Heinrich Pestalozzi (here spoofed as Parapaillozzi) and German pedagogue Friedrich Fröbel (spoofed as Farcet). Unsurprisingly, he also favored boarding schools, since he taught at one himself. Modern readers could interpret 'Mr. Crépin' as a rather sexist story, since Crépin's wife naïevely believes all new theories, even after they have proven to be a lot of harmful nonsense. However, in 'Essais d'Autographie' (1842), Töpffer gave a different interpretation. He explained that Mr. Crépin is actually the one to blame. He is too insecure to trust his own knowledge and experience. If he took more determined and thought-out decisions, most of the problems wouldn't have occurred. Decades later, a try-out sketch for 'Mr. Crépin' was found with Töpffer's manuscripts. It features a fight sequence he eventually dropped from the story. Today this "deleted scene" can be seen in the Museum of Art and History in Genèva.

Histoire d'Albert

Töpffer's next picture story, 'Histoire d'Albert' (1844-1845), was originally published under a pseudonym, Simon de Nantua. This name was a nod to a literary character created by novelist Laurent de Jussieu. In Jussieu's novel, Simon is a conservative moralist. One of his claims is that poverty can be attributed to laziness. 'Histoire d'Albert' follows a similar simpleton character who struggles to make himself useful in society. Albert is a university student who fails in science, chemistry and law. A running gag is that his mother usually understands his problems, while his father simply beats him black and blue. Even when Albert finally has some success as a poet, his dad forces him to return to his studies.

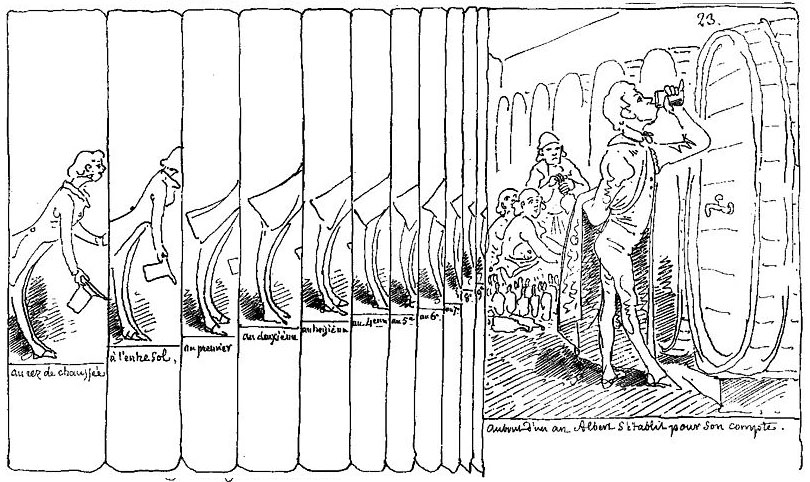

The youngster becomes impassioned by socialist ideas and joins a revolutionary, anti-royalist movement. Riots break out and eventually, Albert flees to get a real job. The college dropout successively works as a dental assistant, podiatrist, wine salesman, encyclopedia salesman, chocolate maker, teacher, candlemaker and salesman. Without exception, he goes broke or gets fired within three months. The scene where he gets drunk on his own wine supply is visually interesting. Töpffer suggests the passage of time through a series of very slim panels which gradually get even slimmer. 'Histoire d'Albert' has a bittersweet ending, with Albert eventually rejoining a revolutionary movement and publishing several newspapers which unite readers by blaming their frustrations on others. This causes riots, but Töpffer cynically concludes: "Albert found himself a reason to exist." The story also features a thinly veiled caricature of Swiss liberal politician James Fazy, who often argued with the conservative-minded Töpffer in parliament.

First comic artist?

Rodolphe Töpffer is traditionally seen as the "inventor" of the comic strip. However, this is a misleading term, which should be viewed in the right context. Since the dawn of man, people have told stories using sequential illustrations. Cave paintings, murals, canvassed paintings, woodcuts, block books, tapestries and miniatures all suited this purpose. Sometimes, the creators added descriptions next to the illustrations. In medieval Europe, some prototypical examples of speech balloons were introduced, although back then they looked like paper scrolls coming from characters' mouths. Most creators of these prototypical picture stories are anonymous. In the 15th century, Dutch painter Hieronymus Bosch and German painter Hans Holbein the Elder, and in the 16th century, Flemish painter Pieter Bruegel the Elder and German painter Hans Burgkmair the Elder, are among the earliest known artists whose sequential illustrated narratives can be identified by name. Their comical, sometimes grotesque characters were a strong influence on later generations of cartoonists. Starting in the 15th century, various European broadsheets and engravings tell stories in successive panels, with text captions underneath the images. Some of them can be attributed to specific artists. In Italy, we have Antonio Tempesta, in France Jacques Callot and in Flanders Frans Hogenberg. German examples can be found in works by Hans Burgkmair the Elder, Lucas Cranach the Elder, Jeremias Gath, Hans Holbein the Elder, Bartholomäus Käppeler, Caspar Krebs, Georg Kress, Der Prager Meister von 1609, Hans Rogel the Elder, Hans Rogel the Younger, Erhard Schön, Johann Schubert, Hans Schultes the Elder, Lucas Schultes and Elias Wellhöfer. A non-print example is Florian Abel's cenotaph for Maximilian I of Austria, which also features a sequential narrative. In the Netherlands, Carolus Allard, Johannes van den Aveele and Romeyn de Hooghe are good examples. In England, Francis Barlow combined his picture stories with speech balloons, or better defined, "speech scrolls". In the 17th, 18th and 19th century, some painters made paintings that need to be grouped together to form a narrative. In the Netherlands, Otto van Veen is one of the first to sign his work. The Englishman William Hogarth made several of these sequential paintings. In the early 19th century, the Spanish artist Francisco de Goya also made sequential series of paintings and engravings.

Most of these early picture stories can be divided into non-fiction and fiction. Stories in the first category visualized historical or religious events. The others were morality tales starring a character doing something good or bad, with the lesson presented in the final panel. In both cases, these picture stories were created to educate audiences. In the late 18th and early 19th century, more cartoonists seem to just want to make people laugh. Their caricatures of politicians or fashions are usually one-panel cartoons, though some make use of sequential images. The pioneers are found in England: Matthew & Mary Darly, James Gillray, Richard Newton, Isaac Cruikshank, Isaac Robert Cruikshank, George Cruikshank, Thomas Rowlandson and William Heath. In 1766, U.S. scientist and prototypical editorial cartoonist Benjamin Franklin made a sequential picture story with speech balloons, but it didn't have much of an impact. Some artists start to draw stories about fictional characters. In 1790s Sweden, for instance, Johan Tobias Sergel and Carl August Ehrensvärd, while Dutch poet Willem Bilderdijk made 'Hanepoot' (1806) for his son. Yet these picture stories were mainly intended for private use. In Japan, the famous painter Hokusai made various sequential illustrated narratives, but these remained unknown outside Japan until the late 19th century. Swedish painter and caricaturist Pehr Nordquist published a picture story titled 'Päder Målare och Munthen' ('Peter Painter and Munthen', 1801). In England, Thomas Rowlandson used several sequential illustrations to liven up William Combe's novel 'Dr. Syntax' (1812-1821) and John Mitford's novel 'Johnny Newcome' (1815/1818), though Rowlandson's work is still close to an illustrated novel, with the images being a mere extra. His fellow countryman William Heath's 'History of a Coat' (1825), 'An Essay on Modern Medical Education' (1825) and 'Theatrical Characters in Ten Plates' (1829) are all genuine picture stories with dialogue underneath the images. In addition, they are historically important for being serialized in a magazine, the Glasgow Looking Glass. In the United States, the Scottish-American cartoonist William Charles used a lot of speech balloons in his cartoons and made one picture story, 'Tom, Tom, the Piper's Son' (1808).

It all goes to prove that most of the elements we associate with comics today already existed in one form or another, long before Töpffer put his first line on paper. He also wasn't the first Swiss to draw a sequentially illustrated narrative. The first one who can be identified to make such a picture story was David Hess with his 'Hollandia Regenerata' (1796). Even so, most of Töpffer's predecessors only made one-shot stories, most of them not longer than a single page. Even the few longer narratives had little impact on the book industry. The only exception was William Hogarth, who made several illustrated narratives, using fictional characters. They were serialized in magazines, adapted into plays and received merchandising on tea cups and saucers. But Hogarth's picture stories were still first and foremost paintings or engravings. They have to be put in chronological order to make sense. He used little to no text, leaving it to the attentive observer to make sense of the images. Last but not least, they served more as morality tales than humorous narratives.

In this regard, Rodolphe Töpffer's picture stories make him the closest to a modern-day comic artist. He was the first known artist to use "autography", at the time a new graphic technique. He drew on a special paper, and then placed a reverse copy on a lithographic stone to trace it. It allowed him to draw very long stories in a quick and efficient way. Töpffer used a stylized, cartoony style. His characters have a comical look and experience humorous adventures. The images aren't juxtaposed stand alone events, but consecutive panels. Each page contains multiple panels, which allows for stronger character development and movement. Text and images fully support one another. Töpffer also didn't rely on a pre-existing story, for his plots and characters came from his own imagination. He additionally used physically impossible gags and other exaggerations, another staple of humorous comics as we know today.

As comic historian Thierry Groensteen pointed out, Töpffer brought several pre-existing graphic ideas together, making it more correct to say that he "reinvented", rather than "invented" comics. For all of his innovations, Töpffer didn't use all the elements we nowadays associate with comics. Following the example of Hogarth's 'Industry and Idleness' and Rowlandson's 'Dr. Syntax', he used no speech balloons and wrote all his narration and dialogue underneath the images. Indeed, most artists who imitated him all used the text comic format too, which remained the dominant format in European comics well into the 1920s.

Dream sequence from 'Histoire de M. Jabot', Töpffer version published in 1833.

Dream sequence from 'Histoire de M. Jabot', redrawn version published by Aubert in 1839.

Artistic evolution

As one can expect from an innovator, Töpffer learned the craft as he went along. He was a decent, but primitive artist. His backgrounds and perspectives aren't always convincing. His characters sometimes look disproportionately small or big. Heads can be too large for their bodies, while limbs occasionally bend in odd ways. By lack of sound effects or movement lines, action scenes sometimes look stiff. In Töpffer's earliest stories, the lay-out is monotonous. Panels rarely differ in size. His earliest story, 'Mr. Vieux Bois', was made up as he went along. Characters fall from one random farcical event into the other. Some plot lines lead to confusing continuity errors. In one scene, Vieux Bois loses his horse which later turns out to have "fallen into a cliff, but survived". However, this fact is only mentioned a couple of pages later, when it's convenient for the plot. Vieux Bois is additionally constantly arrested or locked up, only to escape again one scene later. He also attempts to commit suicide up to five times, which can all come across as repetitive filler rather than a funny running gag.

But along the way, Töpffer grew as an artist. Once he realized there was an audience for his work, he put more effort in communicating his ideas properly. Influenced by theatrical plays, he staged his picture stories in a similar way. The characters are usually at the center of each panel, sometimes looking directly at the viewer. Funny series of misunderstandings build up to an amusing climax with a happy ending. His drawing style improved too. In later stories, Töpffer experimented with his panel sizes. For instance, several narrow panels in a row indicate faster movement. His stories also became tighter and more complex. Töpffer used subplots, numerous side characters and added satirical layers, while maintaining an entertaining flow.

Success

Töpffer's work is particularly a landmark thanks to its commercial success. Before him, most picture stories were paintings, engravings or plates. Only noblemen, clergymen or teachers could afford them. The few picture stories made in the late 18th century and early 19th century had only a limited distribution. Töpffer's comics, on the other hand, were industrialized on a larger scale. The stories were serialized in newspapers, weeklies and monthlies. In between the pure blocks of text, the funny drawings stood out and captivated readers. The serializations helped Töpffer build an audience. Once the story was concluded, readers could buy it in book format. Töpffer was the first cartoonist to publish his comics in small, rectangular books. In English they are called "landscape format", while in other languages they are referred to as "à l'italienne" or "oblong". Just like modern-day comic books, Töpffer's picture stories reached a wide, international audience, even though many editions were released with copied or plagiarized images, most notably in the Albums Jabot series by the French publisher Aubert. Still, Töpffer was the first comic artist to be translated into other languages, including German, English, Dutch, Norwegian, Danish and Swedish. He was also the first comic artist to be published in the United States. And since he had several available comic titles, he was also the first comic artist with a catalog.

First comic essayist

As it seems, Töpffer himself was aware of his historical importance. Just like William Hogarth, he wrote about his work to explain his intentions. In the books 'Essai d'Autographie' (1842) and 'Essai de Physiognomonie' (1845), he discussed his graphic techniques and the nature of his stories. The author saw his "histoires en images" ("stories in pictures") as a separate kind of literature, which he distinguished from stories without images ("histoires sans images"). Töpffer also gave the reader insight in how to make a "good" picture story. He stressed the importance of effective facial expressions, as well as a good correlation between text and image, built around a strong main character. Even today it's a fascinating experience to see an actual comics pioneer explain his line of thought. In that regard, Töpffer can be seen as the first cartoonist who was also a comic essayist, paving the way for people like Jack Hamm, Mort Walker and Scott McCloud.

Death

In 1838, Töpffer's health declined. He suffered from liver and spleen ailments. By 1844, when the magazine L'Illustration invited him to create an exclusive story, he was already too ill to fulfill their request. Instead, he gave him an unpublished story, 'Monsieur Cryptogame'. The ailing artist was able to design a title page, but otherwise it was his final graphic contribution, and the rest of the story was drawn by the French caricaturist Cham. In 1846, Rödolphe Töpffer passed away in his hometown Geneva at the age of 47.

After Töpffer's death, his picture stories were compiled into an anthology format, titled "Histoire en Estampes". He left behind a couple of unfinished comics, of which the manuscripts are nowadays kept at the University Library of Geneva: 'Histoire de Monsieur Fluet et de ses Quinze Filles' ('The Story of Mr. Fluet and His 15 Daughters'), 'Histoire de Monsieur Vertpré et de Mademoiselle d'Espagnac' ('Story of Mr. Vertpré and Mademoiselle d'Espagnac'), 'Histoire de Monsieur de Boissec' ('Story of Mr. de Boissec') and 'Monsieur Calicot' ('Mr. Calicot'). None were ever published as proper books, except for the 1830 story 'Monsieur Trictrac', which appeared in book format a century later, in 1937. The narrative features a bourgeois who travels to Africa to seek the sources of the river Nile. Since John Hanning Speke had discovered the source of the Nile in 1861, this plot device was obviously dated by the time it was finally released.

Legacy and influence

In the mid-19th century and early 20th century, Rodolphe Töpffer's work was widespread. In many countries, reprints and translations of Töpffer's titles were the first published graphic novels (or "comic books"). They inspired local caricaturists, cartoonists and illustrators to draw their own comics. In some cases, they were commissioned by publishers or magazine editors. Many imitated Töpffer's graphic style, titles, characters, lay-out and comedy. In Switzerland alone, he inspired Fritz von Dardel and Charles Dubois-Melly. In France, his influence is felt in the work of Cham, Christophe, Gustave Doré, Eugène Forest, Gabriel Liquier, Timoléon Lobrichon, Nadar and Léonce Petit. German followers are Wilhelm Busch, Franz von Pocci, Carl Reinhardt, Carl Stauber and Adolf Schrödter. In the Netherlands, he inspired Jac A. Hazelaar, Daniël Hoeksema, Ben Mohr, Oscar de Wit and Kees Sparreboom. Töpffer also influenced Richard de Querelles and Félicien Rops in Belgium. Outside Europe, he also gathered a following. In Canada, he could rank Henri Hébert among his disciples, in Brazil Angelo Agostini, while in the United States, James & Donald Read and XOX show Töpfferian elements in their comics.

Some artists outright plagiarized entire characters, narratives and gags from Töpffer. Cham's 'Histoire de Mr. Lajanusse' and 'Mr. de Lamélasse' (both from 1839, published in L'Illustration), weren't subtle about it. Neither was Adolf Schrödter's 'Herr Piepmeyer' (1849). Though it should be pointed out there were no international copyright laws in the 19th century. Since Töpffer was the trendsetter, it was unavoidable that many artists learned the medium by copying him. Without his success, many may have even never considered the idea of creating a comic. Since the 1890s, Töpffer's impact has been overshadowed by the many comic artists who followed in his wake. But his place in history is rightfully solidified as one of the key artists who changed and shaped the medium. Together with Charles Ross & Marie Duval, Wilhelm Busch, Richard F. Outcault and Rudolph Dirks, he remains the most important and influential 19th-century comic artist. Either directly, or through cartoonists who imitated him, Töpffer laid the foundations for the comic strip as an art form as well as an industry.

In 1879, Rodolphe Töpffer received a monumental bust in his home city Geneva. His name also lives on in the award Prix Rodolphe-Töpffer award, handed out annually by the city of Geneva since 1997 in three categories: "Best Comic by a Genevan/Swiss", "Best Foreign Comic" and "Best Comic by Artists Between 15 and 30 years old". Since 2018, Geneva also hands out an award to celebrate the career of a veteran artist. Apart from Goethe, other celebrity fans of Töpffer's comics were art critic John Ruskin, novelist William Makepeace Thackeray, French playwrights Alfred Jarry (famous for 'Ubu Roi') and Jean Cocteau. Jarry even dedicated a chapter of one of his books to Töpffer. And one of Töpffer's own inspirations, J.J. Grandville, named Rodolphe Töpffer "a complete artist", of whom he admired his capability to tell stories with both pictures and text.

Books about Rodolphe Töpffer

Already in the 19th century, Töpffer was celebrated enough to be the subject of two biographies: Pierre M. Relave's 'La Vie et les Oeuvres de Töpffer. Après des Documents Inédits' (Hachette, Paris, 1886) and Auguste Blondel & Paul Mirabaud's 'Rodolphe Töpffer: L' Écrivain, L'Artiste et L'Homme' (Hachette, Paris, 1887). For more modern-day books about Töpffer, Thierry Groensteen and Benoît Peeters' 'Töpffer, l'Invention de la Bande Dessinée' (Hermann, Paris, 1994) and David Kunzle's 'Father of the Comic Strip: Rodolphe Töpffer' (University Press, Jackson, Mississippi, 2007) are highly recommended.

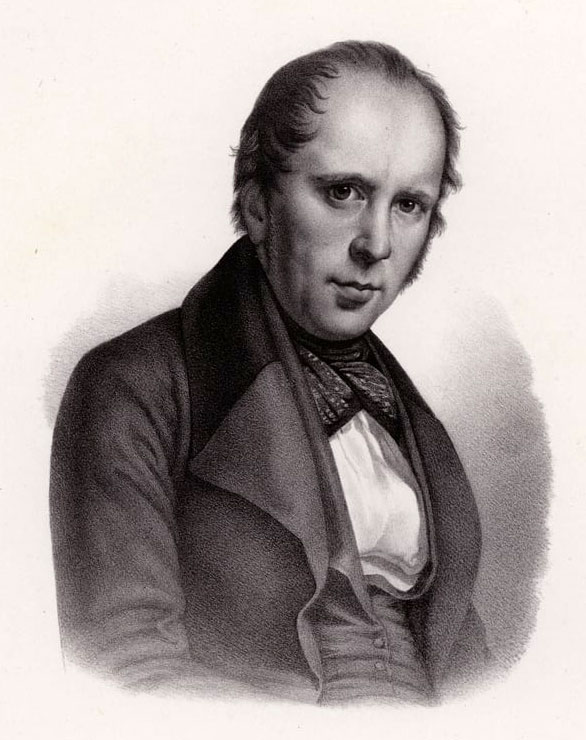

Engraving of Rodolphe Töpffer by an unknown Swiss artist.