'Bobo' comic, from: Bobo Magazine (Spirou #1682, 9 July 1970).

Maurice Rosy was a Belgian comic creator and, between 1956 and 1973, the art director of the Belgian comics weekly Spirou. Initially hired by publisher Dupuis as "man-of-ideas", Rosy's wild imagination proved to be a fruitful source for new series and concepts. Along with chief editor Yvan Delporte, he was responsible for Spirou's success during its Golden Age. They initiated the inventive fold-in mini-books in the magazine's center, while Rosy also oversaw Spirou's art studio and the creation of the audiovisual department TVA Dupuis and the 'Gag de Poche' pocket book series. As a scriptwriter, Rosy was the creator of enigmatic characters like the iconic villain Mr. Choc in the 'Tif et Tondu' series (1955-1968, art by Will), the intelligent secret service dog 'Attila' (1967-1973, art by Derib) and the zany world of the Inzepoket prison, which houses the prisoner 'Bobo' (1961-1972, with Paul Deliège). After retiring from the comic industry, he became a productive illustrator of children's books, magazines and advertisements.

Early life and career

Maurice Rosy was born in 1927 in the Walloon municipality of Fontaine-l'Évêque in the province of Hainaut. The young man worked in his father's spikes and nails factory, while spending his spare time in the Charleroi art scene. In 1953, he managed to get one of his drawings published in the French news weekly Paris-Match. As a pianist in jazz and blues bars, Rosy came in touch with Yvan Delporte, who was by then already employed by the publishing house Dupuis. This company was the homebase of the satirical magazine Le Moustique and the children's comic magazine Spirou. At the time both were in urgent need of modernization, which eventually resulted in Rosy's employment.

Covers for Le Moustique from 3 July 1955 and 28 May 1964 (the 2000th issue).

Man-of-ideas

In 1954, Maurice Rosy was hired by Dupuis as a "man-of-ideas", a profession that didn't really exist, but was created specifically for him. Rosy began publishing cartoons and drawings in Le Moustique, while gradually assisting the magazine's restyling. This was largely established by giving more creative freedom to the editors-in-chief, a function title that didn't even exist under the paternalistic reign of the Catholic Dupuis family. René Hénoumont was put in charge of Le Moustique, while chief editor Jef Anthierens transformed the Flemish counterpart Humoradio into a more independent title, which by 1958 changed its title to Humo. For this magazine, Rosy designed a couple of long-running column logos, among them the magazine's letter section 'Open Venster'. During the early 1950s, the comic magazine Spirou and its Flemish edition Robbedoes were also still rooted in the paternalistic tone of the war years. By 1955, Yvan Delporte officially became editor-in-chief, and in the following year Rosy was appointed artistic director. Together they turned Spirou into a playful landmark of Franco-Belgian comics, where no idea was too crazy and artists were given the freedom to fully explore their talents. This was also made possible because the magazine went from 24 to 32 pages, and most of the licensed American comics were dropped.

Scriptwriter

When he first began at Spirou, Rosy served as sparring partner for the artists team. As writer of the story 'Le Dictateur et le Champignon' (1953-1954), he urged André Franquin to bring back Fantasio's evil cousin Zantafio in Spirou's title comic, and came up with the pink Métomol gag which softens metal into a rubbery substance. Rosy later crafted Incognito City, the modern "city of the future" (according to 1950s standards) for Franquin's 'Spirou et Fantasio' story 'Les Pirates du Silence' (1955), which had background art by Will. His collaboration with Jijé for the episode 'Yucca Ranch' (1954) of the western series 'Jerry Spring' was more of a challenge. The spontaneous Jijé would not hesitate to alter the script whenever he felt like drawing something else, forcing Rosy to use all of his creative powers to keep the story in line. Maurice Rosy was known for sketching full storyboard scripts, a rare working method at the time.

Tif et Tondu

Rosy's biggest challenge was taking charge of the 'Tif et Tondu' series for the young artist Will in 1955. 'Tif et Tondu' was one of the original series in Spirou, created by Fernand Dineur for the magazine's first issue in 1938. Will had taken over the drawing pen in 1949, and up to then had worked with several scriptwriters, including Dineur. Rosy felt the two main stars were too one-dimensional, as they simply fell from one adventure into the other without having much personality. During his tenure on the series, Rosy spoofed this theme in several of his stories. At the start of many tales, Tif and Tondu are usually relaxing from their previous escapades, planning to retire or write their memoirs, when they are launched into yet another wild adventure. Rosy filled his stories with mysterious puppets and villas, strange inventions and a baroque atmosphere, while Will's drawing style blossomed with usage of clair-obscur and depictions of modern architecture, technology and interior designs.

'La Villa du Long–Cri' , artwork by Will. Dutch-language version.

Monsieur Choc

Already in their first collaborative story, Rosy and Will launched one of the most enigmatic villains in European comic book history. Inspired by popular criminals from French pop literature, Pierre Souvestre and Marcel Allain's 'Fantômas' and Maurice Leblanc's 'Arsène Lupin', the masked Monsieur Choc would torture and fool Tif and Tondu in many adventures to come. Tall, stylish, superintelligent and a master in disguises, the man with the cigarette pipe and iron mask is the mastermind behind the criminal organization La Main Blanche ("The White Hand"). His greeting card alone sent shivers down his victims' spines. After his introduction in 'Tif et Tondu Contre la Main Blanche' (first published in Spirou between 6 January and 2 June 1955), Rosy and Will brought him back on several occasions. Choc not only fools his adversaries, but also the readers. In his second appearance, 'Le Retour de Choc' (1955), his true identity is apparently revealed, but the next story already explains that the bearded and bespectacled face was nothing more than a latex mask. And while in 'Passez Muscade' (1956) Choc appeared to have died in a plane crash, he survived only to be arrested for good in 'Plein Gaz' (1957). Choc indeed disappeared from the series for many years, and didn't return until 'Choc au Louvre' (1964). In between, Will had briefly left the publishing house Dupuis, during which the 'Tif et Tondu' series was taken over by Marcel Denis, who made two more down-to-earth stories from scripts by respectively Rosy and Marcel Remacle.

The reintroduction of Choc was a return to form in more ways than one, as the artist Will also returned to the series. During the 1960s episodes, Choc's sinister plots become even more grotesque. In 'Le Réveil de Toar' (1966), Choc awakens a legendary menhir knight who lay dormant under the ground, while in 'Le Grand Combat' (1967) the master villain hijacks dreams and turns them into nightmares. Rosy's final contributions to 'Tif et Tondu', the diptych 'La Matière Verte' (1967) and 'Tif Rebondit' (1968), relied more on slapstick and suggested that the writer had lost much of his inspiration. He then left the writing duties to Maurice Tillieux, who transformed the series into a true detective comic. For years, Rosy had kept the rights to the character of Monsieur Choc to himself. By 1984, he allowed Tillieux's successor Stephen Desberg to use him again in new stories. The 'Tif et Tondu' comic remained a regular feature in Spirou until 1997, the final years under the reigns of scriptwriter Denis Lapière and artist Alain Sikorski.

New talent

As Spirou's art director, Rosy was also a talent scout. He for instance helped artists from his art studio get their solo careers going, such as Marcel Remacle who started his humorous pirate comic 'Le Vieux Nick' in 1958. With his background in graphic art, Rosy brought a new aesthetic to Spirou's pages, inspired by press cartoons and UPA's 'Mister Magoo' animated shorts. In addition to the magazine's generally round and highly detailed comic pages, Rosy included comics with a more minimalist and stylized art approach by René Hausman ('Les Aventures de Saki', 1957), Eddy Ryssack ('Patrick Lourpidon', 1960), Guy Bara ('Max L'Explorateur', 1964) and Claire Brétécher ('Les Naufragés', 1968). For Bara, Rosy also wrote one serial with the explorer Max, 'Max et le Triangle Noir' (1964).

On occasion, Rosy had to use clever tricks to persuade his publisher Charles Dupuis of an artist's talent. In sharp contrast to Rosy, Dupuis was for instance not impressed by the work of the young artist Jean Roba. Rosy therefore let Roba draw an unsigned full page of his new family comic concept, colored and printed it, and put it between the material for the upcoming issue. When discovering the page, Dupuis was instantly attracted to the new comic, and asked who the maker was. With his 'Boule et Bill' gag comic, Jean Roba was a mainstay in Spirou for decades to come.

Part of a 'Bobo' mini-book by Rosy and Kornblum from Robbedoes #1655 (1 January 1970). Dutch-language version.

Mini-books

With Rosy as his scriptwriter, Roba got the opportunity to introduce his characters in the short story 'Boule Contre les Mini-requins' (1959), as part of the new section of fold-in mini-books. Based on an idea by Yvan Delporte, Spirou's center quire featured a complete comic strip, which the reader could extract from the magazine and fold into a mini-book. Launched in 1959, it was originally a spot for Spirou's core team to experiment and play around. Peyo, for instance, launched the solo career of his famous blue Smurfs in this section, while MiTacq spoofed his own boy scout adventure comic 'La Patrouille des Castors' with the funny animal strip 'La Patrouille des Zom' and Franquin made a story with one of the more obscure side characters from 'Spirou et Fantasio', the little boy Noël.

Spirou's mini-books also became the perfect breeding ground for new talent. Rosy and Yvan Delporte gave the anonymous artists from the Dupuis art studio the opportunity to showcase their skills on these pages. Charles Degotte, Louis Salvérius, Serge Gennaux, Paul Deliège and Jacques Devos all made their debut in the mini-books and then transferred to Spirou's regular pages. Assistants from Studio Peyo were also featured with solo comics, like Lucien De Gieter and Francis. Other artists remained staples in the mini-books alone, such as Mike and Noël Bissot. Some series were launched in the mini-books section and then became popular features in the normal pages of Spirou, for instance the previously mentioned Smurfs and 'Boule et Bill', but also 'Le Flagada' (1961) by Degotte, 'Génial Olivier' (1963) by Devos and 'Sam et l'Ours' (1968) by Lagas and Deliège. Another important newcomer was the prisoner 'Bobo' (1961), a co-production between Rosy himself and Paul Deliège.

Bobo

Since the stories of the mini-books in Spirou were printed in a small format, the space within the panels was limited. The mini-books were therefore drawn in a simplistic style and relied heavily on slapstick humor. For that reason, the concept of the 'Bobo' series was quite simple. The main character Bobo was a convict, who tried every method to escape from prison, aided by his outside assistant Julot-les-pinceaux. Because of his inventiveness, Bobo is nicknamed the "Mozart of escapes". However, none of his escape tunnels, self-constructed ropes and cleverly used prams, balloons and other objects actually help him get away. Despite his efforts, Rosy and Deliège's anti-hero remains interned in the zany prison of Inzepoket. Rosy initially saw 'Bobo' as a pleasant distraction from his regular work, a fun comic with an unlikeable hero. But the series proved to be more enduring. The cast was expanded with the more brutal fellow inmate Joe la Candeur and Inzepoket's fatherly, light-hearted and gullible director, who seeks harmony in his prison and mostly enjoys St. Honoré cakes made by Inzepoket's pastry chef. Later came the poor prison guard Dupavé, who had to walk around all day with a spare stone of the prison wall, which had been replaced after a break-out attempt by Bobo. Rosy generally served as scriptwriter and Deliège as the artist, but on some occasions Deliège or Rosy made a solo story. After about ninety stories, the collaboration between the two men came to an end. In addition to 'Bobo', Rosy and Deliège additionally created the one serial inspector Bébert (1963-1964).

Between 1969 and 1973, Rosy continued the 'Bobo' series on his own, aided by his writing partner M. Kornblum. Bobo gradually left the mini-books and made his entrance in Spirou's normal pages, which, as Rosy once remarked, was in fact Bobo's only successful break-out attempt. In 1970, the character got its own four-page Bobo Magazine section, completely written, drawn and designed by Rosy and Kornblum. Presented as the Inzepoket newsletter, it fully showcased Rosy's experimental nature. Short news messages were alternated with advertisements and short comic strips in a film format. This magazine-within-the-magazine also had a separate comic feature called 'Planète Pompus' (the "Apple Planet"). Bobo Magazine however failed to catch on, and was dropped after only a dozen appearances.

'Planète Pompus'/ 'Appelplaneet' (Robbedoes #1687, 13 August 1970).

Other activities for Dupuis

During his tenure with Dupuis, Rosy was involved in several innovative projects. In 1955 and 1956, he served as editor-in-chief of Risque-Tout, a tabloid-sized comic magazine initiated for Dupuis by Georges Troisfontaines. In 1959, Rosy was one of the founders of TVA Dupuis, the company's new audiovisual department. Inspired by the Belvision studios of main competitor Lombard, the TVA team worked on animated films with the characters from Spirou magazine, most notably Peyo's Smurfs. Eddy Ryssack was put in charge of the studio, which also employed Francis Bertrand, Vivian Miessen, Jean Delire, Charles Degotte and cameraman Raoul Cauvin. Rosy participated as a scriptwriter to the independent animated TVA shorts 'Teeth is Money' (1962) and 'Le Crocodile Majuscule' (1964).

Another important project headed by Rosy was the 'Gag de Poche' collection (1964-1968). This new series of pocket books featured remounted editions of Spirou's own comic series, but also introduced the French-speaking audience to American newspaper comics like Charles M. Schulz's 'Peanuts', V.T. Hamlin's 'Alley Oop' and the cartoons of Virgil Partch. The collection marked the first book publications of Rosy and Deliège's own 'Bobo' and Guy Bara's 'Max l'Explorateur'. In the pages of Spirou, Rosy and Yvan Delporte additionally launched 'Le Télégraphe' (1965-1966), a section with fun facts and news items illustrated by Eddy Ryssack, Guy Bollen, Carlos Roque, Michel Matagne and other artists.

'Le Télégraphe', from Spirou #1465 (12 May 1966).

Non-Dupuis scriptwork

Occasionally, Rosy worked for other publishers and magazines as well. His cartoons appeared in magazines like Paris-Match, Adam and PAN. In 1955, he wrote the story 'Les Diables à 4' of the 'Chick Bill' comic by Tibet, published in Tintin magazine. With Will, he made stories of 'Marco et Aldebert' (1962-1965) in Record. Around the same period, he collaborated with Jo-El Azara on the short stories 'Cadeaux de Noël' (Tintin, 1962), 'Suivez l'Oeuf' (Pilote, 1963) and the series 'Mayflower' (Pilote, 1963-1965).

Abstract comic story from Spirou #1465, 12 May 1966.

The experimental Rosy

In his spare time, Maurice Rosy made abstract drawings, inspired by Saul Steinberg, Chinese calligraphy and the CoBrA art movement. Rosy enjoyed experimenting with abstract forms, far from the conventions of caricature. He sometimes made a comic page in this avant-garde style as well. One of his surreal pages in bright colors with hat-like creatures in a seemingly Martian landscape intrigued Yvan Delporte, who published it in Spirou #1465 of 1966. Since it was printed with no introduction or explanation, it is no surprise that the page puzzled both readers and editors. In the following year, it appeared in the anthology 'Les Chefs d'Oeuvre de la Bande Dessinée' by Planète, which presented the diversity of French-language comics of the time.

Other artists who have experimented with abstract comics are Roberto Altmann, Rino Feys, Lewis Trondheim, Andrei Molotiu, Roger Price and Wasco.

Attila

When Rosy quit writing 'Tif et Tondu', he embarked upon a new project. 'Attila' (1967-1973) was launched in 1967 and drawn by Derib, one of Peyo's former co-workers. The concept was again inventive. The title hero is a highly intelligent dog, trained by the Swiss secret service to read, write and talk in the four national languages of his country. His powers of deduction and reflexes were also enhanced, as were his qualities in negotiation. The dog is adopted by mister Bourrillon, the manager of a dog kennel, who became his companion on all of his adventures, starting with 'Un Métier de Chien' (1967). The little boy Odée joined the cast in 'Attila au Château' (1968), followed by another talking dog, Z14, in 'Attila et le Mystère Z14' (1970). Only four adventures of 'Atilla' were created by Derib and Rosy, as the two men were both on turning points in their careers. In 1973, Derib created the realistic 'Buddy Longway' comic for Tintin, a series that would require all of his time and effort from then on. Rosy, on the other hand, left Dupuis.

The mysterious "M. Kornblum"

By the late 1960s, Maurice Rosy had begun a collaboration with a person known only as M. Kornblum. For years, it remained a mystery to readers who this person really was. But from 1968 on, all of Rosy's productions were signed with "Rosy M.M. Kornblum". Maurice Kornblum actually had a background in trading. He ran a shop in sports and camping equipment, but also had a creative spirit. After the departure of Spirou's chief editor Yvan Delporte, Rosy felt more and more alienated from his profession. A new generation of artists had arrived, and the "man-of-ideas" felt he lost his grip. He found a working partner in Kornblum, who not only provided him with plot ideas, but also had a good sense of finances. Kornblum served as Rosy's agent, and the two men opened their own studio, which they called the "Bureau Centralisateur de Distribution et d'Estension" (B.C.D.E.), literally the "Central Office for Distribution and Expansion". An ambitious name for their activities in comic book writing and book editing, although the duo also developed its own perfume line, called Roko. As both Rosy and Kornblum were in the process of going through divorce, they decided to live together in a large house in the fields of Baisy-Thy. Even though the two were merely friends and creative partners, their combined household and "new age" way of living led to much speculation and gossip.

Leaving Dupuis

However, not everyone was too pleased with the contributions of Maurice Kornblum. Deliège was no fan of the man's work, and left the 'Bobo' comic in 1969. Derib also disliked Kornblum's ideas for 'Attila', for instance the introduction of Z14, and made the transition to Tintin magazine. By 1973, Rosy and Kornblum's creative spark had worn out, and their partnership ended. Rosy left the Belgian comic industry altogether, and moved to Paris. Before he left, he sold the rights of 'Bobo' to Dupuis, after which the comic was continued with Paul Deliège as writer and artist until his retirement in 1996. Deliège enriched the Inzepoket cast with several new characters, and his stories were collected in sixteen albums by Dupuis. During the 1980s, a lost 'Attila' script by Rosy and Kornblum was eventually drawn by Didgé and published in Spirou magazine under the title 'Bak et Flak Étonnent Attila' (1987), without Rosy's knowledge or consent. Kornblum's name wasn't even mentioned at all.

'Modes' (Le Monde-Dimanche, 27 January 1980).

Parisian years

In Paris, Rosy focused on a career as an advertising artist and illustrator. Through agencies like Grey, CLMBBDO, Havas and Accent, he designed advertising campaigns for Malabar chewing gum, Vittel mineral water and Chanel, among many other clients. He made cartoons and illustrations for newspapers and magazines such as Le Monde (1979-1994), Le Nouvel Observateur (1980), and for the children's magazines J'Aime Lire, Pomme d'Api, Les Belles Histoires and Astrapi. Rosy also made illustrations for children's book series published by Bayard Presse, Nathan, Bordas and Hatier, including works by Jacques Duquesne ('Candido Mène l'Enquête', 1980), Jacqueline Held (the 'Croktou' series, 1986-1992) and Béatrice Rouer (the 'Jennifer et Laetitia' series, 1990-2006).

'Malabar'.

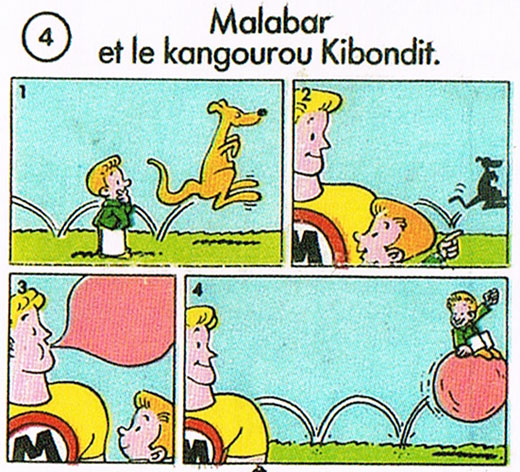

Malabar

In 1977, Rosy was assigned by the Grey agency to make comic strips with 'Mr. Malabar', the mascot of Malabar chewing gum, created in 1969 by Jean-René Le Moing. Rosy made the first set of pantomime comics for the Malabar wrappers, in which the muscular hero always ends up saving the day by blowing bubbles with his gum. Until the mid-1990s, many artists followed in his footsteps, including Philippe Poncet de la Grave, Frank Margerin, Jean-Claude Poirier, Philippe Luguy, Mic Delinx, François Dimberton, Régis Loisel, Olivier Taffin, Yannick, Michel Motti, Artur Rainho, Pierre Tasso and Brice Goepfert.

Other later-day comic work by Rosy included the Mode section of Le Monde-Dimanche and the children's series 'Lucas Ramel' (1985-1993) in Pomme d'Api and 'Basile' in Maximilien. The latter was collected in two books by Nathan in 1993. In 1995, Maurice Rosy met his new wife, Danièle Gérault. She was a wine saleswoman, and from then on Rosy regularly provided artwork to wineries and the catering industry. After 2002 he gradually retired from his professional career.

Legacy

The mid-2000s marked a renewed interest in Rosy's career as a comic book writer. Dupuis began collecting its patrimony in luxury collections, including the 'Tif et Tondu' series (2007), as well as 'Attila' (2010) and the early small-format stories of 'Bobo' (2010). In 2010, the publishing house Hibou launched the complete 'Bobo' in book collections; the first volume containing the stories made by Rosy and Deliège. Dupuis also captured its cultural legacy in documentary books, like the one about editor-in-chief Yvan Delporte, for which Rosy was extensively interviewed by Christelle and Bertrand Pissavy-Yvernault. The couple was also responsible for the dossier in the 'Attila' anthology, which finally revealed more information about Rosy's collaboration with Maurice Kornblum. To coincide with the 75th birthday of Spirou magazine, editor José-Louis Bocquet asked Rosy to capture his own memoirs in comics format. Maurice Rosy began working on the project, but was not able to complete it, as he passed away in his Paris home on Saturday 23 February 2013. Dupuis published the book posthumously under the title 'Rosy C'est La Vie!' (2014), combining Rosy's drawings with the transcript of an interview with the artist by Bocquet.

Shortly before his death, Rosy had given his blessing to Will's son Éric Maltaite and Stéphane Colman to explore the origins of the enigmatic Monsieur Choc. Unfortunately, he didn't live to see the end result: the critically praised spin-off trilogy 'Choc' (2014-2019). On 1 June 2019 Mr. Choc received his own statue in La Hulpe, Belgium, sculpted by Joachim Jannin, nephew of Frédéric Jannin. Remarkably enough, neither Tif or Tondu have a statue yet at this point.

Yvan Delporte introduces Maurice Rosy to Charles Dupuis (from: 'Rosy, C'est La Vie!').