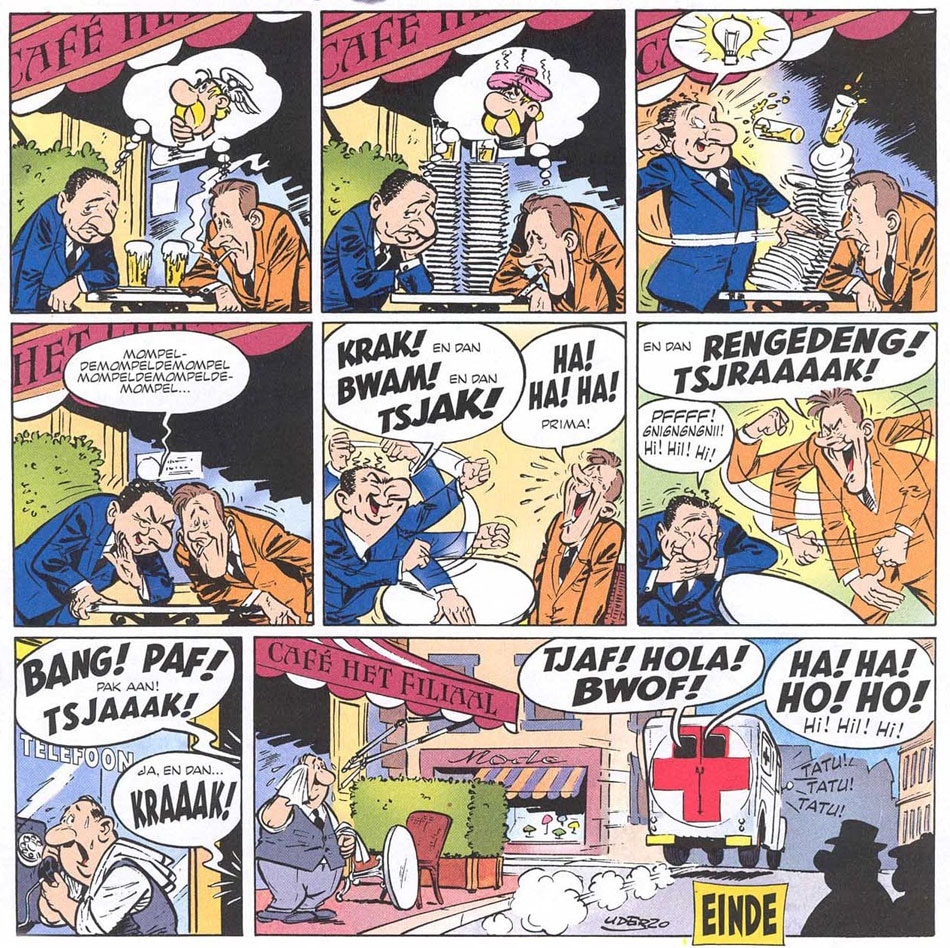

Goscinny and Uderzo brainstorming for an 'Astérix' comic. Comic by Albert Uderzo. Dutch-language version.

René Goscinny was a legendary writer of humor comics, whose high level type of storytelling and witty, satirical humor changed the landscape of European comics. Through colorful and iconic characters and engaging stories, he became a master of the running gag, amusing puns, great slapstick violence and clever cultural-historical references. Together with Albert Uderzo, he created a sensation with 'Astérix' (1959- ), one of the bestselling European comic series in the world, along with Hergé's 'Tintin'. Popular with children and adults alike, the adventures of the indomitable Gaul are among the few comics admired by intellectuals, because of their great satire, vivid depiction of the Gaulish-Roman era and many double layers in language and cultural-historical references. In the same tradition, Goscinny's name is attached to another international bestseller, the cowboy comic 'Lucky Luke' by Morris. Even though he didn't join its production until nine years after its creation, he reshaped it into a hilarious parody of the western genre. Goscinny additionally wrote the popular book series about the naïve school boy 'Le Petit Nicolas' (1954-1965), illustrated by Jean-Jacques Sempé, while his other notable comic co-creations included the brawny Native American 'Oumpah-Pah' (1958-1962) with Uderzo, the dictatorial grand vizir 'Iznogoud' (1962- ) with Jean Tabary and the nonsensical education parody 'Les Dingodossiers' (1965-1967) with Marcel Gotlib. And still, these are only a few of the dozens of comics he penned gags and narratives for.

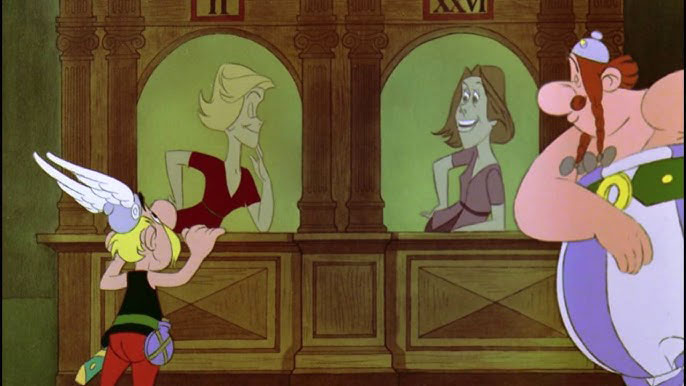

One of the few comic writers of his generation as famous as the artist, he was a strong advocate for equal rights and appreciation for this often ignored profession. This closed several doors in the early stages of his career, but eventually led to him joining Jean-Michel Charlier, Albert Uderzo and other associates in the launch of the groundbreaking French comic magazine Pilote (1959-1989). Serving as its chief editor from 1963 to 1974, he played a huge part in its commercial success, introducing popular comic series and new creators, and helping the publishing house Dargaud grow into a powerful rival to the leading Belgian comics companies Lombard and Dupuis. Besides comics, Goscinny also wrote the scripts for animated feature adaptations of his creations, such as the classic films 'Astérix et Cléopâtre' ('Asterix and Cleopatra', 1968), 'Daisy Town' (1971), 'Les 12 Travaux d'Astérix' ('The 12 Tasks of Asterix', 1976) and 'La Ballade des Dalton' ('The Ballad of the Daltons', 1978). His most lasting legacy may be that he managed to get children interested in more sophisticated comedy, while proving to adults that comics could be enjoyed on a higher level.

Cover illustration by René Goscinny for the student magazine Quartier Latin, Octobre 1944.

Early life and career

René Goscinny was born in 1926 in Paris as the son of a Jewish chemical engineer and freemason of Polish descent. Originally from Warsaw, his father Stanislas ("Simha" in Polish) was the third son of rabbi Abraham Goscinny, and had moved with his brother to Paris in 1906. René Goscinny's mother Anna Béresniak came from a Ukrainian family that had settled in the French capital around the same time. Besides René, the couple also had an earlier son, Claude (1920-2004). From his mother's side of the family, René Goscinny was the first cousin of the philosopher Daniel Béresniak (1933-2005). When Goscinny was two years old, the family moved to Argentina, where his father received a position with the Jewish Colonization Association, JCA. However, the Goscinnys' lifestyle was not particularly Jewish or colored by religion, exemplified by the typically French names they gave their children. In Buenos Aires, René attended a French-language school, where around the age of fifteen, he began filling his notebooks with Disneyesque drawings.

From a young age, Goscinny wanted to become a comic artist, inspired by Alain Saint-Ogan's 'Zig et Puce', Louis Forton's 'Les Pieds Nickelés' and Walt Disney's comics. Later in life, he also expressed admiration for Tex Avery, Walt Kelly and Harvey Kurtzman (who became one of his good friends even before founding Mad Magazine). Avery and Kurtzman proved to Goscinny that one could create hilarious comedy enjoyable for children and adults alike, but on different levels. Goscinny was also a huge fan of film comedians Laurel & Hardy, Buster Keaton, Peter Sellers, Louis de Funès and The Marx Brothers.

Graduated from high school in 1943, only a month before his father died, Goscinny found a job at a tire factory. In the meantime, he published his first illustrations and writings in the school bulletin Quartier Latin and the student magazine Notre Voix. By the time he was laid off from his factory work, he became a junior illustrator at an advertising agency, although he later remarked that he basically had to copy artwork from the Saturday Evening Post. He also spent some time working as an assistant to an Austrian advertising artist.

Harvey Kurtzman, John Severin and René Goscinny in 1948.

American years

During World War II, the Goscinnys were lucky to live in Argentina and so escape the Holocaust in Europe. After the war, they learned that several of their relatives in Europe had died in Nazi concentration camps. By 1945, one of Goscinny's last surviving maternal uncles settled in the United States, and informed his sister and nephew by letter of the endless opportunities he encountered there. It motivated Goscinny and his widowed mother to move to New York City. René's older brother Claude stayed in Argentina until 1956, experiencing firsthand the military regime of Juan Peron. However, shortly after his arrival in New York City, René Goscinny went to Europe to fulfill his military service in the French Army. He served in Aubagne in the 141st Alpine Infantry Battalion, and was also the regiment's official illustrator. After his discharge, he returned to the USA and settled in Brooklyn to pursue a career as an illustrator/cartoonist. Many sources over the years have incorrectly assumed that Goscinny was a fully self-taught artist. However, when he was in New York, he received drawing lessons from the German illustrator and engraver Fritz Kredel (1900-1973), who mostly illustrated fables and fairy tales.

'Water Pistol Pete and Flying Arrow'.

During a period of a year-and-a-half, Goscinny offered his services and presented his portfolio to publishers, agencies and studios, but all in vain. His luck changed in late 1948, when he got the opportunity to work at the Charles William Harvey art studio. Based on 1151 Broadway in New York City, the studio was run by Charlie Stern, Bill Elder and Harvey Kurtzman, and frequented by other comic book artists like John Severin and Jack Davis. At the studio, Goscinny was mostly tasked with drawing backgrounds, lettering texts and making layouts. In 1949 and 1950, Goscinny and Kurtzman collaborated on a variety of children's puzzle books for Kunen Publishers, including 'The Little Red Car', 'Round the World' and 'The Jolly Jungle'. As writer and artist, Goscinny was solely responsible for the jigsaw puzzle books 'Water Pistol Pete and Flying Arrow' (1949) and 'The Monkey in the Zoo' (1949).

Unfortunately for Goscinny, Kunen went bankrupt shortly afterwards, leaving him, again, without a job. He remained close to Kurtzman and his former colleagues who, from 1952 on, became regulars in the humorous comic book series Mad, founded by Kurtzman. The early issues of Mad, which later became a magazine, had an enormous impact on Goscinny, both as a comic writer and later as a magazine editor at Pilote. Interestingly enough, in Mad issue #3 (February-March 1953), the story 'Sheik of Araby' (scripted by Kurtzman, drawn by John Severin) is set in the French Foreign Legion, where one soldier has the name "Goscinny". Although his face isn't modelled after Goscinny's, the name does appear to be an inside joke on Kurtzman's behalf.

Subtle reference to René Goscinny by Harvey Kurtzman and John Severin in Mad #3 (February-March 1953).

World's P. Presse

While in the United States, René Goscinny also got acquainted with two Belgian comic creators who were staying in Connecticut: Joseph Gillain, better known as Jijé, and Maurice de Bevere, who signed his work Morris. As both artists were affiliated with Spirou magazine in Belgium, this encounter initiated a turning point in Goscinny's career. After some ill-fated attempts by Jijé and Goscinny at creating an animated film together, Jijé eventually returned to Europe, which indirectly also instigated Goscinny's departure for the continent. Through Jijé, Goscinny had been introduced to the Belgian entrepreneur Georges Troisfontaines, whose World's P. Presse agency packaged comics and editorial pages for the magazines of Éditions Dupuis (Spirou's publisher). In 1951, Goscinny traveled to Europe by boat to offer them his services. Morris stayed in the USA, but later became one of Goscinny's main associates.

As luck would have it, Goscinny's arrival in France happened to coincide with Troisfontaines establishing a Parisian division of his agency. In the French capital, Goscinny began his association with World's P. Presse and its sister organization International Press, a newspaper syndicate run by Troisfontaines' brother-in-law, Yvan Chéron. Initially, Goscinny was active in several roles, including comic artist, writer of editorial sections and art director. Between 1951 and 1956, he was tasked with writing several how-to columns for the Belgian women's weekly Bonnes Soirées, using a variety of female pseudonyms, of which Liliane D'Orsay was the most common. One of his regular features was the long-running advice column 'Qui à Raison?' ("Who Is Right?"), which he eventually illustrated personally. An early example of his satirical writing was the family chronicle 'Sa Majesté Mon Mari' ("His Majesty My Husband"), illustrated by Albert Uderzo (1951-1953) and then Charlie Delhauteur (1953-1956).

In 1952, Troisfontaines sent Goscinny back to the USA to set up TV Family, an attempt by Éditions Dupuis to launch an American version of their radio and TV guide Le Moustique. However, the market proved saturated, and the magazine lasted only three months and fourteen issues, the final one appearing on 20 February 1953. In 1955-1956, Goscinny returned to New York once again, editing the cartoon anthologies 'Cartoons the French Way' and 'French and Frisky' for Lion Books, which contained work by European cartoonists like Sempé, Ami, Morez, Siné and Fred.

'Dick Dicks', written and drawn by Goscinny.

René Goscinny: comic artist

In the first half of the 1950s, Goscinny still divided his time between writing scripts and cartooning. When he applied with World's Presse, he presented them a self-created comic strip about a bumbling detective, 'Dick Dicks' (1951-1952). Starting in September 1951, the feature ran for nine stories in La Wallonie, a socialist daily circulating in the Belgian province of Liège. Consisting of nine stories, 'Dick Dicks' was reprinted in La Libre Junior between 1955 and 1956.

During the period 1953-1954, Goscinny made illustrations, cartoons and caricatures for Le Moustique magazine, using pseudonyms like René Maldecq, René Macaire and Jacob. The final comic that Goscinny drew himself was 'Le Capitaine Bibobu' (1955-1956), starring a grandfather, nostalgic to his Navy years, who tries to convince his grandson Loulou of the beauty of sailing. Between November 1955 and April 1956, 'Le Capitaine Bibobu' ran in Risque-Tout, a short-lived companion magazine to Spirou, published in tabloid format. After its conclusion, Goscinny decided that his talents lay not with drawing, but instead with writing.

'Le Capitaine Bibobu', written and drawn by René Goscinny.

René Goscinny, comic scriptwriter

During his time with World's P. Presse and International Press, Goscinny came to blossom as a fruitful striptwriter for many of the magazines and newspapers that both agencies provided with content. For Bonnes Soirées, Goscinny developed the comic heroine Sylvie, a modern young woman with whom the readership could easily identify. After writing about a dozen gags in 1952, Goscinny passed the writing duties to the artist Martial, who continued this domestic sitcom on his own for over forty years. That same year, Goscinny also wrote three installments of the historical feature 'Les Belles Histoires de l'Oncle Paul', drawn by Eddy Paape and Pierre Dupuis, and published in Spirou magazine. However, he didn't find much fulfillment in the dry, educational content, and gladly left the feature to its main writer, Octave Joly.

Between 1952 and 1957, Goscinny was a regular contributor to La Libre Junior, the children's supplement of the Catholic newspaper La Libre Belgique, to which International Press provided the content. In 1952, he succeeded Jean-Michel Charlier as the scriptwriter of 'Fanfan et Polo' (1952-1953), a comic drawn by Dino Attanasio about two turbulent youngsters whose search for adventure often causes havoc. In turn, Charlier quickly took over the writing of 'Alain et Christine' (1953), an adventure feature about two children that René Goscinny had started with Martial.

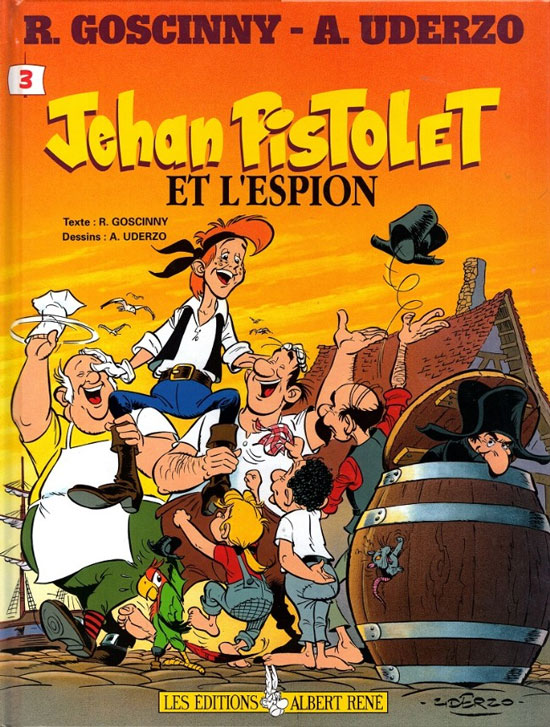

1954 cover page of La Libre Junior featuring the 'Luc Junior' comic and an album cover for 'Jehan Pistolet'. Art by Albert Uderzo.

Collaboration with Albert Uderzo

During this time, fellow World's creators like Jean-Michel Charlier and Victor Hubinon became good friends and future collaborators of Goscinny. But his most significant team-up was with French comic artist Albert Uderzo, who illustrated Goscinny's columns in Bonnes Soirées. Even though their personalities differed - Goscinny was extroverted, playful and intellectual, Uderzo more anticipating, pragmatic and traditional - they proved a perfect mix for some of the best creations in Franco-Belgian comic history. Their first joint comic creations appeared in La Libre Junior, starting with the humorous series about wannabe pirate 'Jehan Pistolet' (1952-1956). In 1954, they additionally created the paper's mascot, 'Luc Junior' (1954-1957), whose adventures were later continued by Sirius and then Greg. Between November 1954 and June 1955, the newspaper supplement also ran the duo's only realistic comic serial, starring shark hunter 'Bill Blanchart'.

Out of all of their creations in La Libre Junior, 'Jehan Pistolet' had the most longevity, and was the first showcase of Goscinny and Uderzo's talent for creating pun and gag-filled adventures against a historical backdrop. Debuting on 26 June 1952, the story was set in the 18th century and revolved around a young waiter called Jehan, who works in a tavern in Nantes. Dissatisfied with his job, he decides to become a privateer and buys a ship, "La Brave". He assembles a crew consisting of various colorful characters, including his second captain Hugues, cooks Bertrand and Pierrot, cannoneer and navigator Gilles, tiny sailor P'tit René (a caricature of René Goscinny) and Jasmin the parrot. Jehan and his crew work for the French king and sail the seven seas looking for treasures and new colonies, or to fight off villainous pirates. Several elements of 'Jehan Pistolet' already hint at Goscinny and Uderzo's later work. 'Jehan Pistolet' satirized a specific genre, in this case nautical and pirate stories, and much like 'Astérix', the protagonists celebrate every happy ending with a banquet. 'Jehan Pistolet' allowed Uderzo to show off his rich illustration work and talent for visualizing Goscinny's funny scripts.

'Lucky Luke': 'Les Cousins Dalton' and 'Billy the Kid'.

Lucky Luke

Through World's P. Presse, Goscinny had made his modest debut in Spirou as the writer of three episodes of the educational series 'L'Oncle Paul'. However, his appearances in the magazine were mostly anonymous, when helping out the two Belgian artists he had met in the United States. In 1956, Goscinny wrote the 20-page story 'L'Or du Vieux Lender' for Jijé's realistic western comic 'Jerry Spring'. Unsatisfied with the liberties Jijé took in amending his script, it remained a one-time collaboration. Morris' western comic, 'Lucky Luke', on the other hand, was more up Goscinny's alley, particularly since it was humorous in style. Since 1946, Morris had written and drawn stories starring the "poor lonesome cowboy" on his own, but had difficulties coming up with longer, cohesive plots. By the time Morris returned to Belgium in 1955, he asked René Goscinny for help with the scripts. When the latter took over the writing of "the cowboy who shoots faster than his shadow", the series took flight.

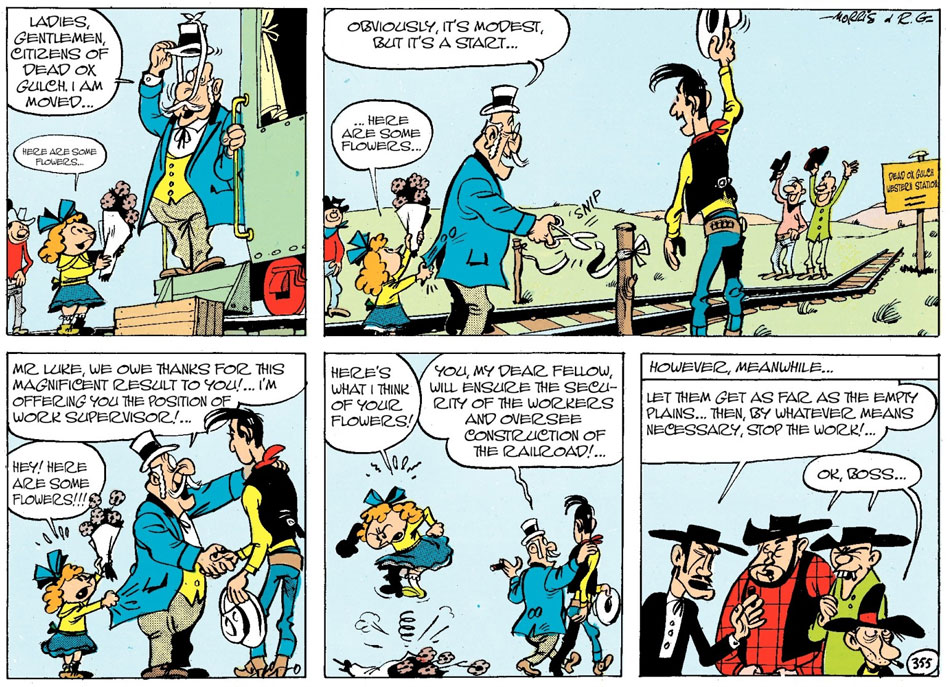

At the time, being a writer for comics wasn't considered an actual profession, and magazine editors and publishers only dealt with the artists. As a result, Goscinny worked directly for Morris and the publisher initially wasn't even aware of his involvement. Starting with the 1955 break-out episode 'Des Rails sur la Prairie', Goscinny's contributions to 'Lucky Luke' remained anonymous - except for an occasional "RG" initial in the pages - until the story 'Les Rivaux de Painful Gulch' in 1961. After that, the stories received a joint credit byline. Goscinny quickly uplifted the comic's overall tone and cast. Over the years, he introduced countless new and memorable characters, most notably the outlaws Joe, Jack, William and Averell Dalton (the cousins of the "original" Daltons, who Morris had killed off in an earlier episode), the dimwit prison dog Rantanplan, and comic renditions of real-time Wild West legends like Billy the Kid and Calamity Jane. The adventures of the poor lonesome cowboy became a brilliant satire of Western clichés, including every stock character: ultra-fast sharpshooters, careless gamblers who are frequently tarred and feathered, grouchy old-timers, lynch-happy mobs, morbid caretakers, monosyllabic Native Americans who make spelling mistakes while sending smoke signals, Chinese laundry owners, African-American laborers, siesta-holding Mexicans, overly feared outlaws and the cavalry riding in to save the day.

By the time the comic moved from Spirou to Gosinny's own magazine Pilote in 1968, the stories were enhanced with less child-friendly elements. Gun battles became more prominent and the saloon scenes were livened up with female dancers in sexy stockings. Morris and Goscinny's collaboration lasted until shortly before Goscinny's death in 1977, resulting in 37 albums published by Dupuis and then Dargaud. After that, Morris collaborated with many other scriptwriters, all of which tried to capture the tone and spirit that Goscinny had brought to the series.

Creator's rights

In the post-war years, the Belgian comic industry had professionalized, spearheaded by popular magazines like Spirou and Tintin and the upcoming comic album market. Publishers became powerful corporations. While independent creators who worked directly for publisher Dupuis were generally rewarded with royalties and ownership over their books and creations, authors working through an agency like World's P. Presse only received their wages, while the agency owned the copyright. Comic writers like Goscinny and Jean-Michel Charlier were generally left out of any negotiations or rights' ownership to their series. In 1956, Charlier and Goscinny tried to gather all World's P. Presse's artists and establish a "creator's manifest" to stipulate better payment, ownership to their rights and, most of all, recognition for their professional expertise. When World P. Presse agency owner Georges Troisfontaines caught wind of this attempt at unionization, he was not pleased. He made Goscinny the fall guy and fired him. Out of solidarity, Charlier and Albert Uderzo both left the agency, along with the firm's former publicity manager Jean Hébrard. However, both Charlier and Goscinny remained involved with Spirou magazine as scriptwriters - Charlier for his main series 'Buck Danny' (drawn by Victor Hubinon) and 'La Patrouille des Castors' (drawn by MiTacq), and Goscinny as ghost writer for 'Lucky Luke'. For Raymond Macherot, Goscinny later wrote a solo serial for Spirou with 'Pantoufle' (1966), the stupid cat from Macherot's funny animal series 'Sibylline'.

Édipresse/Édifrance publications: Pistolin and La Grande Parade.

Édipresse/Édifrance

After their departure from World's P. Presse, the team of Goscinny, Uderzo and Charlier expanded their activities for other publishers and clients. Still in 1956, they joined Jean Hébrard in the launch of Édipresse/Édifrance, a syndicate for press, communication and advertising productions. With Uderzo as lead illustrator, Goscinny and Charlier were tasked as copywriters for advertisements and comic features. The syndicate launched publications like Clairon for Fabrique-Union toys, Pistolin (1955-1958) for the Pupier chocolate company and the monthly Jeannot (1957-1958), a joint venture between Nappey watches, Klaus chocolate and Gilac plastic. Goscinny was responsible for writing both Pistolin and Jeannot's title comics, which were drawn by Victor Hubinon under the pen name Victor Hugues. Several of Goscinny and Uderzo's earlier creations reappeared in the new Édipresse projects; 'Jehan Pistolet' was reprinted in Pistolin under the title 'Jehan Soupolet', and in 1957 'Bill Blanchart' returned in the Edifrance magazine Jeannot. Among the other advertising titles launched by Édifrance were Milliat Frères Magazine (1956) for Milliat Frères pasta, for which Goscinny and Uderzo created the front-page comic feature 'L'Étonnante Aventure du Seigneur Raviolitos', and La Grande Parade (1959), a one-shot magazine accompanying an annual event by the radio stations Radio-Luxembourg and Radio Monte Carlo.

An extremely rare trial issue of an Édifrance newspaper supplement called Le Supplement Illustré (1956) consisted of new creations by Goscinny with other Franco-Belgian legends like Morris ('Fred-le-Savant'), Jijé ('Max Garac'), Uderzo ('Antoine l'Invincible'), André Franquin ('Mimile, Garçon de Bureau') and Will ('Marlène Mannequin'). The project, however, never saw the light of day and all its comics faded in obscurity. One of the characters from Le Supplement Illustré that was picked up again was mobster Fred-le-Savant, who starred in Morris and Goscinny's 1956 gangster parody 'Du Raisiné sur les Bafouilles' (the title was a spoof of the French gangster cult movie 'Du Rififi Chez Les Hommes'). The story, set in the more shady quarters of Paris, featured Goscinny's trademark humor, peppered with Morris' love for caricaturing film stars (one of the criminals is modeled after actor Jean Gabin). However, when the film noir spoof was serialized in the satirical magazine Le Hérisson, the printing agency Opera Mundi demanded the exclusive rights to all comics printed in its magazines. As Goscinny and Morris refused, the narrative was abruptly interrupted after only 13 half pages.

In 1957, Goscinny and Will repurposed Le Supplement Illustré's 'Marlène Mannequin' into 'Lili Mannequin' (1957-1959), a comic strip about a beautiful fashion model, syndicated by Édifrance to the Parisian magazine Paris-Flirt and the Belgian publication L'Âne Roux. After six months, Will passed the pencil to Christian Godard. A rare entry in Goscinny and Uderzo's catalog was 'Monsieur et Madame Plume' (1958), a gag strip syndicated by Édifrance to Paris Flirt (an earlier strip had appeared under the title 'Routine' in Radio-Télé).

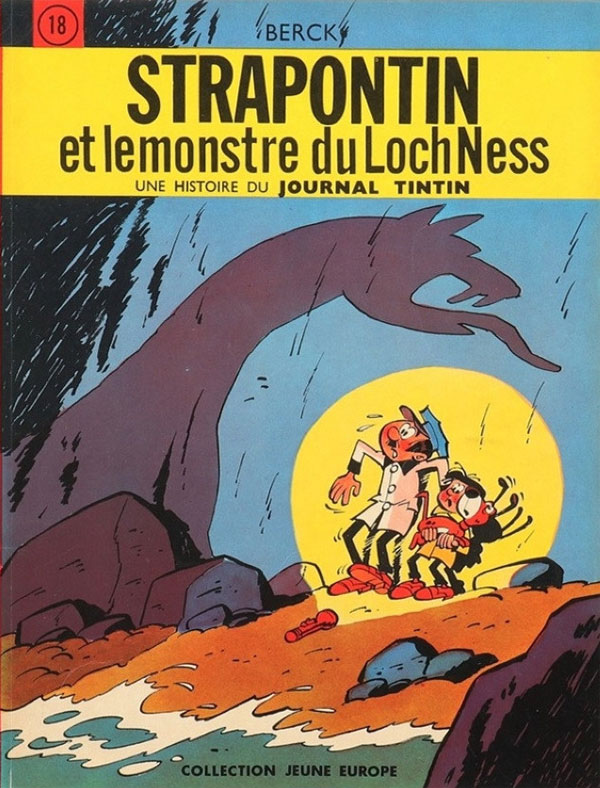

'Strapontin' (art by Berck) and 'Signor Spagheti' (art by Dino Attanasio).

Tintin magazine

By the time of his discharge from the World's P. Presse agency, René Goscinny had built a reputation as a reliable and talented scriptwriter and humorist. In late 1956, he was contacted by André Fernez, the editor-in-chief of Tintin magazine, to come and work for the publishing house Le Lombard. Between 1956 and 1965, Goscinny was one of Tintin's productive scriptwriters, either helping out artists with their existing series, or creating new ones. As the magazine originally contained mostly serious adventure serials, Goscinny helped expand its humor features, starting with one to three-page stories. Between 1956 and 1959, he contributed gag ideas to André Franquin's sitcom comic 'Modeste et Pompon', creating the character of the pushy Mr. Dubruit, Modeste's nextdoor neighbor who always overstays his welcome.

Goscinny's early Tintin work also included several contributions to the magazine's "animated cartoon in comic strip form" section. This series of two-page stories relied heavily on slapstick humor, with each episode looking like images from a movie reel, complete with vignettes with double perforated strips in black with little white dots. In 1956 and 1957, Goscinny contributed scripts with many of this feature's characters, writing stories for Raymond Macherot's little duck 'Klaxon', Jo Angenot's funny animal strip 'Mottie la Marmotte', Tibet's strange extraterrestrial alien 'Globul Le Martien' and Bob De Moor's clumsy school teacher 'Monsieur Tric'. In a similar slapstick fashion, Goscinny co-created several one-shot characters, like 'Oscar Baudruche' and 'Wa-pi-ti' with Rol (1957), 'Kenott et Fûté' with Paul Coutant (1957), and 'Paco Marmota' with Jo-El Azara (1958).

For Tibet, Goscinny also wrote one episode of the humorous western comic 'Chick Bill', namely 'La Bonne Mine de Dog Bull' (1957). Together, they created 'Alphonse' (1957-1958), a series of short stories in which the title character tried out a new job in each episode, always with disastrous results. The seventh and final episode was drawn by François Craenhals. Between 1957 and 1959, Goscinny provided scripts for the early short stories for Maurice Maréchal's humorous mystery comic 'Prudence Petitpas', about an old lady who solves crimes and mysteries in the style of Agatha Christie's Miss Marple. When Goscinny left the series in 1959, Maréchal continued it on his own, switching from two or three-page stories to longer serials.

Between 1957 and 1959, Goscinny wrote gags and short stories for Dino Attanasio's new creation 'Signor Spaghetti', later shortened to 'Spaghetti'. The stereotypical Italian and his sidekick, cousin Prosciutto, were basically self-mockery for Attanasio, who was an Italian immigrant himself, though such gentle ethnic comedy was also an ace up Goscinny's sleeve. In each episode, Spaghetti tries out a new job, always without success. Between 1960 and 1965, the duo featured Spaghetti and Prosciutto in longer episodes, which were also collected in book format. By 1965, Goscinny's workload became too heavy, and he left the writing of 'Spaghetti' to other people, including Lucien Meys, Michel Greg, Roger Francel, Yves Duval and Attanasio's wife Joanna.

With Berck, Goscinny created the humor comic 'Strapontin' (1958-1965), about the slapstick adventures of an unlucky cab driver, whose service is frequently requested by the scientist Petitpois. The name "strapontin" was Parisian slang for the many Russian refugee cab drivers that worked in the French capital after the Russian Revolution. In 1965, Goscinny was replaced by Jacques Acar, who continued the globe-trotting adventures of Strapontin, his son Wimpi, Gérard the dog and professor Petitpois, until 1968.

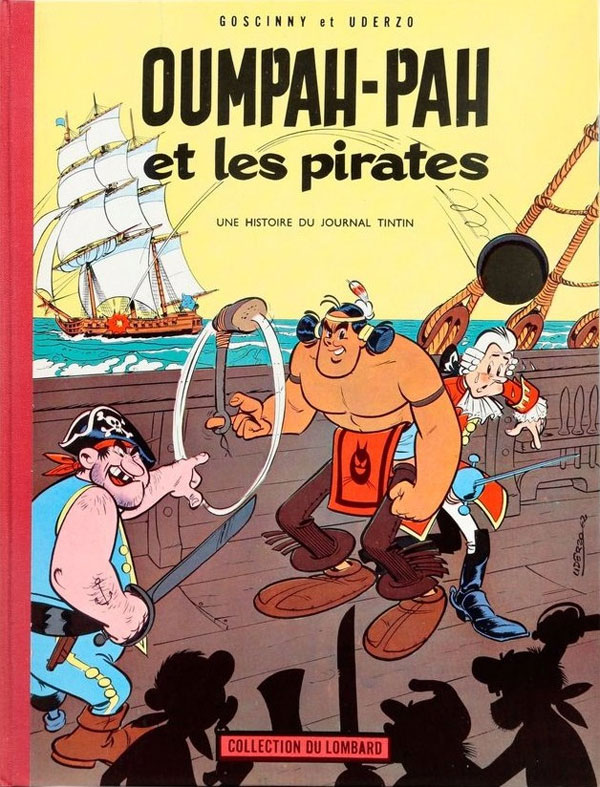

Oumpah-Pah

However, René Goscinny's most notable contributions to Tintin magazine were again made in collaboration with Albert Uderzo. After creating three short stories with the characters 'Poussin et Poussif' (1957-1958), featuring an energetic toddler and an unfortunate Great Dane dog, they dusted off an old concept they had developed. In fact, the giant Native American 'Oumpah-Pah' was the first joint creation they had done back in 1951, but at the time they couldn't get it published. When it was finally greenlighted by Tintin, the comic debuted on 2 April 1958. 'Oumpah-Pah le Peau-Rouge' (1958-1962) is set in Canada (New France) during the 18th century, when French colonialists explored the country. The main character Oumpah-pah is a hefty, brave and strong Native American who befriends a scrawny dignified French military officer, Hubert de la Pâte Feuilletée.

Goscinny studied documentation thoroughly to know more about the time period, but didn't hold himself back when it came to poking fun at every conceivable cliché about Native Americans. Just like in his 'Lucky Luke' stories, their animalistic names and communication through smoke signals were running gags. European settlers are mocked with the same wit and nobody can deny that Oumpah-Pah is effectively the hero. Goscinny double-layered his scripts with historical allusions. Much like how the Gauls in 'Astérix' frighten the Romans, the Native Americans scare off colonials with their physical strength and hide in bushes and trees. The series has been translated into many languages, including Dutch ('Hoempa Pa'), German ('Umpah-Pah'), Danish ('Umpa-Pa'), Norwegian ('Ompa-Pa'), Swedish ('Oumpa-Pa'), Finnish ('Umpah-Pah'), Spanish ('Oumpah-Pah'), Portuguese ('Humpá-Pá'), Italian ('Oumpah-Pah'), Polish ('Umpa-Pa Czerwonoskóry') and Russian ('Умпах-Пах').

La Famille Moutounet

In 1959, Goscinny and Uderzo made another comic series for Tintin, 'La Famille Moutonet', starring a grandfather with a military background who is tormented by his overly busy grandchildren, Totoche and Mimi. It only lasted two short stories, but was nevertheless in 1961 revived as 'La Famille Cokalane' in the French edition of Tintin. Having basically the same cast and set-up, this reboot came about at the instigation of Pétrole Hahn, whose shampoo products were sponsored at the bottom of each comic strip. Since their products were not available in Belgium, 'La Famille Cokalane' appeared only in the French edition of Tintin. After a first episode drawn by Albert Uderzo, the next fifteen installments were illustrated by a different artist, who has not yet been identified.

Further magazine work

Besides Tintin, several other magazines requested the services of Goscinny. Between 1957 and 1959, Goscinny and Uderzo took over the comic feature 'Benjamin et Benjamine', starring the mascot of Benjamin magazine. The comic was previously created by Christian Godard, and then continued by Jen Trubert and Roger Lécureux. In 1958 and 1959, Goscinny appeared in Vaillant magazine with gags about the bumbling duo 'Boniface et Anatole', drawn by Jordom, and with the short-lived 'Pipsi' feature drawn by Christian Godard.

'Le Petit Nicolas'. 'Le Petit Nicolas à des Ennuis'.

Le Petit Nicolas

During Goscinny's newfound independence, another important collaboration that expanded was with the French cartoonist Jean-Jacques Sempé. Ever since their first meeting in 1953, when they were both new in Paris, Sempé and Goscinny hit it off. In 1955, at World's P. Presse, they created the first version of 'Le Petit Nicolas' (1955-1956). The character originated in a couple of cartoons that Sempé had made for the magazine Le Moustique in 1954. Charmed by the character, the agency requested Sempé to turn his creation into a comic strip. Since he had little to no knowledge of comics, the cartoonist asked Goscinny to write the feature, who in turn adopted the pen name Agostini. Between 25 September 1955 and 20 May 1956, 26 episodes of the 'Petit Nicolas' comic ran in Le Moustique. When World's P. Presse fired Goscinny, Sempé too left the agency out of loyalty to his friend.

On 30 March 1959, Goscinny and Sempé resumed their collaboration, when 'Le Petit Nicolas' reappeared in the form of illustrated text serials in the French newspaper Sud-Ouest Dimanche. From 17 December 1959 on, 'Le Petit Nicolas' ran simultaneously in Goscinny's comic magazine Pilote. The new text format turned 'Le Petit Nicolas' into an overnight success. Goscinny wrote the narratives in the first person, making them the naïve everyday life accounts of a Parisian boy, the smallest in his class. Nostalgic and innocent, enhanced with the poetic illustrations of Sempé, the stories form an idealized depiction of childhood in 1950s France. Even though the series is generally seen as children's literature, the original target audiences were adults (Sud-Ouest) and adolescents (Pilote). Many of the narratives were inspired by Sempé's childhood experiences of spending holidays in school colonies and playing soccer with friends. Goscinny expanded Nicolas' world with colorful secondary characters, such as the boy's gluttonous best friend Alceste and several classmates, including the lazy Clotaire, the dreamy Jochaim and the hothead Maixent.

Between 1960 and 1964, publishing house Denoël released the 'Petit Nicolas' stories in five annual book collections. After their national success, the 'Le Petit Nicolas' books were translated into many languages, including Russian, Turkish, Japanese, Chinese, Vietnamese and Hebrew. In most languages, the boy's name remains the same or is turned into a localized spelling of "Nicolas". Only in Danish he is known as 'Jeppe' and in Turkish as 'Pitircik'.

Debut issue of Pilote (29 October 1959).

Launch of Pilote

During the second half the 1950s, the Édipresse/Édifrance team produced several magazines commissioned by commercial clients. In late 1958, they were approached by advertising executive François Clauteaux to create a special paper for youngsters, a mix of comics with articles about current affairs, science and history, modeled after Paris-Match magazine. Joining in on the venture were Radio-Luxembourg and two top editors of the regional Centre Républicain newspaper. After several dummies, the first issue of Pilote magazine appeared on 29 October 1959. In its first years, the magazine underwent several editorial, stylistic and personnel changes, with the radio connections becoming less prominent and an increasing representation of the comics content. In early 1961, the magazine was bought over by Éditions Dargaud, the publishing house that also released many of Pilote's comic series in book format, and so became an important competitor to the leading Belgian comic publishers, Dupuis (Spirou) and Le Lombard (Tintin).

From the start, Goscinny and Jean-Michel Charlier served as Pilote's main scriptwriters - Goscinny for the humor content, Charlier for the more serious adventure serials. Previous Goscinny creations reappeared in Pilote, for instance new episodes of 'Le Petit Nicolas' (1959-1965), and reprints of 'Jehan Soupolet' (1960-1961). However, Goscinny also developed several new creations in Pilote's pages. In the first issue, Goscinny and Christian Godard created the adventures of the sailor 'Jacquot le Mousse' (1959). Among his other early co-creations were the sporadically appearing 'Les Divagations de Monsieur Sait-Tout' (1961-1963), a comic about a silly professor, drawn by Martial, and 'Tromblon et Bottaclou' (1962-1963), a feature drawn by Christian Godard about the confrontations between a 19th-century bandit and a policeman. Together with Jean Tabary, he additionally created 'Valentin le Vagebond' (1962-1963), about a poetic and likeable vagabond. However, none reached the same longevity and iconic status as his new creation with Albert Uderzo, 'Astérix le Gaulois' ('Astérix the Gaul').

First panels of 'Astérix le Gaulois' in the dummy issue of Pilote (1959).

Astérix

For their new comic feature in Pilote, René Goscinny and Albert Uderzo initially picked out a comic version of the medieval folk tale about the trickster fox Reynard, 'Le Roman de Renart'. However, it turned out comic artist Benjamin Rabier had already beaten them to the idea and Jean Trubert was also preparing a comic book version about Reynard. Goscinny decided to delve deeper, all the way back to the starting point of all French history books: Gaulish culture. At school, everybody learned about the Gaulish chieftain Vercingetourix and his brave resistance against the Romans. Since the time period was such common knowledge among French readers, Goscinny and Uderzo could have all the fun they wanted with this setting, because everybody would get the references. 'Astérix' takes place around the time of Caesar's conquest of Gaul (ancient France). As the famous title page of every album explains: Caesar apparently hadn't conquered all of Gaul. One tiny village in the western-northern French region Brittany (Bretagne) keeps resisting the Roman oppressors. This is the place where Astérix and his fellow villagers live. The choice for this homebase was self-evident. Goscinny wanted it to be near the ocean, in case storylines would require the characters to sail to other countries. Uderzo favored Bretagne because he had lived there during World War II. And since the province was famous for its many archaeological examples of Gaulish culture - such as the famous menhirs of Carnac - it was a done deal. At the time, the creators weren't aware that there already had been two comics about ancient Gaul, namely Jean Nohain and Poléon's 'Totorix' and Fernand Cheneval's 'Aviorix'. Luckily, as it turned out, because otherwise they might have dropped that idea too.

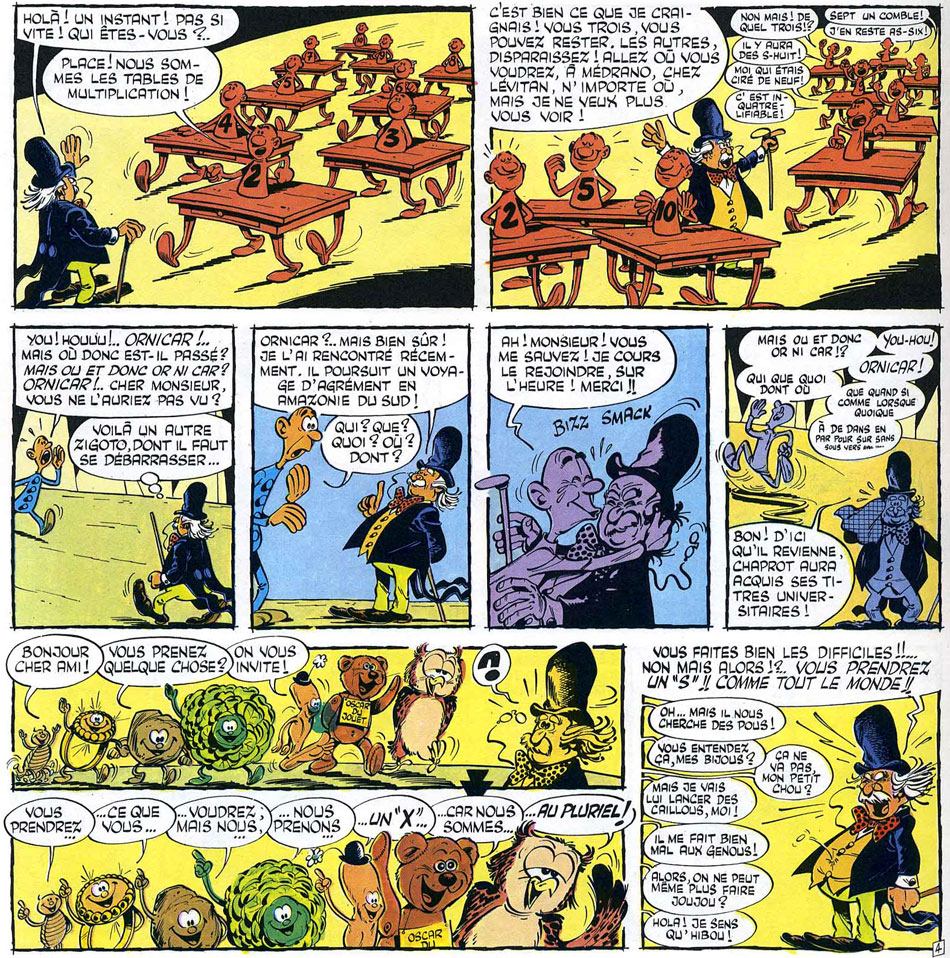

All in all, 'Astérix' was a runaway success from the start. Sales rose with each album and Pilote eventually turned the character into the magazine mascot. Despite being the most "European" comic of all time, 'Astérix' also managed to become a global success. The series has been translated into more than 115 languages and dialects, including Arabic, Bengali, Chinese, English, Hindi, Indonesian, Japanese, Persian, Russian, Thai and Turkish. All across the world, it shares the stage with Hergé's 'Tintin' as perhaps the most recognizable European comic ever, and many schools have used 'Astérix' comics to help their students read and learn French.

Cover illustration by Albert Uderzo for Pilote issue #347 (16 June 1966) and the 'Astérix' story 'Le Combat des Chefs' ('The Big Fight').

Astérix: characters

Starting in the first issue of Pilote on 23 October 1959, the debut serial 'Astérix le Gaulois' ('Asterix the Gaul', 1959), already established most of the recurring cast. Goscinny deliberately gave Astérix a name starting with the first letter of the alphabet, so the series could end up in the first chapter in future comic book encyclopaedia. While Astérix is small and hot-tempered, he is nevertheless very smart. Together with the druid Panoramix (Getafix in the English translation), they are easily the most intelligent people in the village. Panoramix provides all the villagers with a magic potion which makes the Gauls strong enough to beat up the Romans time and time again. The only person not allowed to drink the potion is Astérix' best friend, the local stonecutter Obélix, who fell into the cauldron when he was just a small boy and is therefore already strong enough. A brawny man, he enjoys beating up Romans, eating and hunting for wild boars. Unfortunately he is not very bright and in constant denial over his obesity. However he is such a charming doofus that he is easily everyone's favorite character, particularly with children. Abraracourcix (Vitalstatistix) is the village's self-important chieftain who is carried around on a shield, as was common among Celtic tribes, but constantly falls off due to his carriers' clumsiness and stupidity. Assurancetourix (Cacofonix) is the local bard, but sings so awfully that everyone always tries to shut him up, particularly the blacksmith Cetautomatix (Fulliautomatix) who often keeps a hammer near. The final recurring character introduced in Astérix' debut album is Julius Caesar. He acts as the town's nemesis and is frustrated that he can't conquer the Gaulish village. Yet he is not portrayed as diabolical either. When defeated or humiliated, he usually shows some grace or a sense of fair play towards the Gauls. He even helps them punish some of his subordinate centurions or far more villainous Romans.

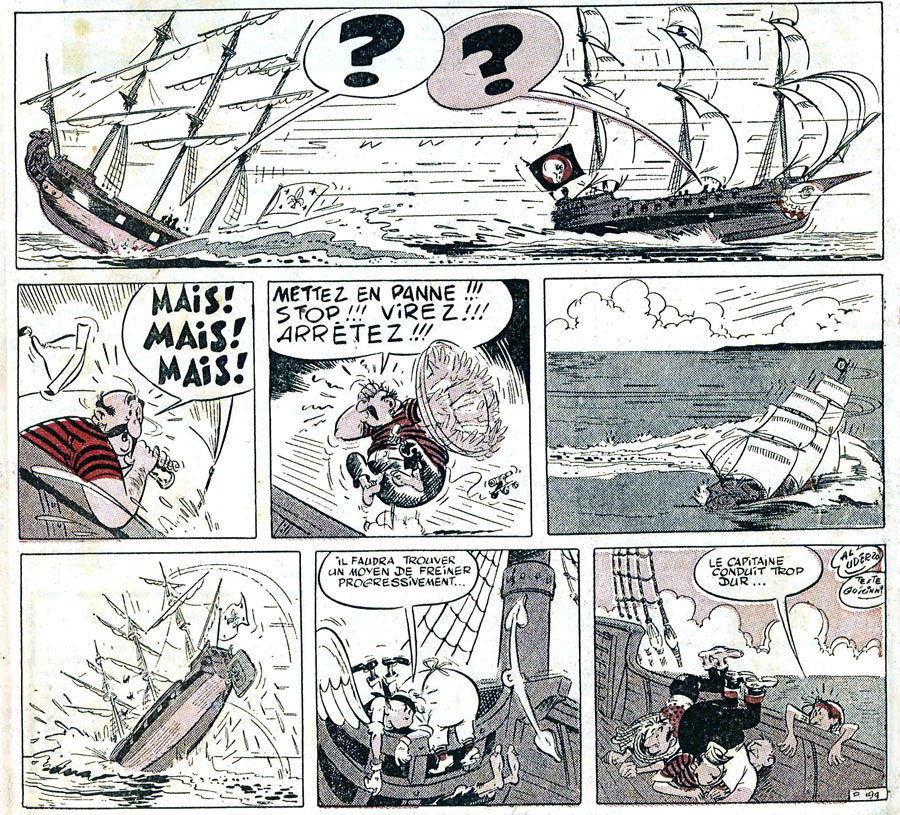

Other recurring villains in the series are the pirates, although they are less of a threat. They made their debut in 'Astérix Gladiateur' ('Asterix the Gladiator', 1962) where they make the fatal mistake of attacking Astérix and Obélix. Originally they were just intended as a shout-out to the pirate comic 'Barbe Rouge' by Jean-Michel Charlier and Victor Hubinon, which also ran in Pilote. The three main pirates are even directly modeled after Barbe Rouge, the one-legged Triple-Patte and Baba the crows' nest look-out. But they quickly became a running gag in every 'Astérix' album. No matter where the buccaneers travel, they always happen to come across "the crazy Gauls" somewhere, much to their own misfortune. Since 'Barbe Rouge' was unknown outside Continental Europe, the reference to Charlier and Hubinon's comic was lost on most foreign readers. Today, now that 'Barbe Rouge' has more or less fallen into obscurity, they have become a prime example of a parody which outlived the original spoof material.

René Goscinny and Albert Uderzo at the Asterix anniversary in 1967.

Another major character, Obelix' dog Idéfix (Dogmatix), actually started out as a running gag but quickly became a full cast member. All throughout the story 'Le Tour de Gaule d'Astérix' ('Asterix and the Banquet', 1963), Astérix and Obélix are followed by a tiny, white mustached dog, who is noticed and adopted by Obélix in the final strips. Pilote organized a contest to find a name for the canine. Four young readers, Hervé, Dominique, Anne and Rémy came up with "Idéfix", a pun on the French word "idée fixe" for an obsessive idea. Other regulars in the franchise are the village elder Agecanonix (Geriatrix, 1962) and his far younger wife (1970). Chieftain Abraracourcix also received a feisty partner in 1964, Bellefleur (Impedimenta). Finally, in 1969, fish monger Ordralfabetix (Unhygienix) was introduced. His merchandise is never fresh and so sparks off numerous village fights. But despite all of their internal struggles, the Gaul village is still united against their common enemy, the Romans. Every story ends with the villagers celebrating at a large, round table in the middle of the forest, while drinking beer and eating roasted wild boars. Even Assurancetourix is allowed to be there, but out of precaution against his possible warbling is bound and gagged against a tree.

Jours de France

Goscinny was one of the few writers able to work with both traditional comic artists, like Uderzo and Morris, and press cartoonists, like Sempé and Coq. With the latter, he worked on three features for the weekly magazine Jours de France. In 1960, he took over the writing of Coq's 'Docteur Gaudéamus' (1960-1967) from France-Soir's publisher Marcel Dassault. Until 1967, he wrote the narratives for this feature, starring a strange professor who has developed a rejuvenating serum, which makes him regain his early childhood. In 1993, the comic served as the inspiration for the comedy film 'Coup de Jeune' by Xavier Gélin. Between 1967 and 1969, Goscinny and Coq continued their collaboration with 'La Fée Aveline', starring the young modern fairy Aveline Potiron, who lives in present-day France. Born from the love of a rose and a butterfly, Aveline was condemned by the fairy Carabosse to lose her magical powers when she fell in love. In April and May 1962, they also made the short-lived humor feature 'Yvette' for Jours de France.

'Iznogoud' - 'Les Complots du Grandvizir Iznogoud' and 'Le Tapis Magique'.

Iznogoud

In 1962, René Goscinny was also present in Record, a new children's monthly published as a joint venture by Dargaud and the Catholic publishing house La Bonne Presse. With Will as artist, he created the magazine's title comic, 'Record et Véronique' (1962-1963), starring Record's blond mascot and an equally unruly girl. Goscinny's best-remembered creation for Record was however 'Les Aventures de Caliph Haroun El Poussah', a series later known under the title 'Iznogoud', made in collaboration with the artist Jean Tabary. In the 1961 episode 'La Sieste' of his 'Le Petit Nicolas' series, Goscinny had Little Nicolas listen to a tale about a "caliph and his evil grand vizier". This provided the spark for Goscinny and Tabary's famous comic series, set in ancient Baghdad. In the debut issue of Record (15 January 1962), the first episode of 'Les Aventures de Caliph Haroun El Poussah' saw print. The short stories initially focused on caliph Haroun El Poussah (Haroun El-Plassid in the English translation), a good-natured, but lazy and dim-witted monarch. He spends most of his time sleeping, eating and drinking, while his reign is threatened by his evil grand vizier, Iznogoud. The short-sized and short-tempered politician desperately wants to overthrow Haroun, which he voices in his iconic redundant catchphrase: "Je veux devenir caliphe à la place du caliph!" ("I want to become caliph instead of the caliph!").

In each storyline, Iznogoud hatches up a convoluted scheme to depose the caliph. He is aided by his loyal servant Dilat Larath (Wa'at Alahf in the English translation), who carries out the dirty, exhausting, dangerous and disgraceful parts of the plans. Dilat is usually the first and only one to realize the major flaws of his master's plans. Needless to say, all of Iznogoud’s coups backfire, either by bad luck or his own stupidity. Iznogoud goes through preposterous lengths to achieve his goal. The feisty vizier organizes complicated uprisings, coups and foreign invasions. He tries to pit rival despot Sultan Pullmankar (Sultan Streetcar in the English translation) against the caliph, but to his chagrin, they actually get along fine with each other. For his ploys, Iznogoud collaborated with Genghis Khan, Adolf Hitler and even Satan himself. Many stories start with Iznogoud meeting djinns, fairies, magicians, mad scientists and - in one story - extraterrestrial aliens.

In 1968, 'Iznogoud' transferred from Record to Pilote, which by then contained all of Goscinny's signature series. From 21 October 1974 on, 'Iznogoud' also ran in the Sunday paper Journal du Dimanche under the title 'L'Ignoble Iznogoud Commente L'Actualité' ("The Honorary Iznogoud Comments on Current Affairs"). Presented as a weekly gag comic, Goscinny and Tabary created exclusive material with jokes offering topical political and social satire, often directly inspired by current internal affairs in France.

Charlier and Goscinny starring in the photo comic 'Les Ecumeurs du Montana' by Giraud and Mézières (Pilote #552, 4 June 1970).

Editorship of Pilote (1960-1973)

After several editorial changes, René Goscinny and Jean-Michel Charlier were put back at the helm of Pilote magazine in September 1963. By then, 'Astérix' had become a commercial smash, and so Goscinny was basically given free reign by publisher Georges Dargaud. In 1967, he was even named director of the magazine. The Goscinny-Charlier era ushered in a period of transformation, experiment and new talent. Largely tasked with bringing in new artists, Goscinny was open to innovation, and didn't let his own personal taste prevail. Over the course of the 1960s, the Goscinny-Charlier tandem greenlighted groundbreaking new series like the satirical 'Achille Talon' by Greg (1963), the hard-boiled western 'Blueberry' by Charlier and Jean Giraud (1963), and more intellectual science fiction series like 'Valérian et Laureline' by Jean-Claude Mézières and Pierre Christin (1967). In 1968, both 'Lucky Luke' and 'Iznogoud' transferred from their respective magazines to Pilote magazine, bringing all of Goscinny's series together in one publication. A new creation during this period was 'La Forêt de Chênebeau' (1968), a funny animal series of short stories filled with Goscinny's typical wordplay, drawn by Mic Delinx.

Editorially, the magazine shifted towards satire and current affairs, inspired by the playful tone of Mad Magazine. While Pilote remained the homebase of more traditional artists like Raymond Poïvet, Victor Hubinon and Christian Godard, it also opened its doors to satirists like Claire Brétécher, Gotlib and Alexis, the absurdism of Nikita Mandryka, Fred and F'Murr, the anarchistic humor of Reiser and Cabu and more stylistic experimentation of Jacques Tardi, Jean Solé and Philippe Druillet, as well as a group of press caricaturists operating under the "Grandes Gueules" banner.

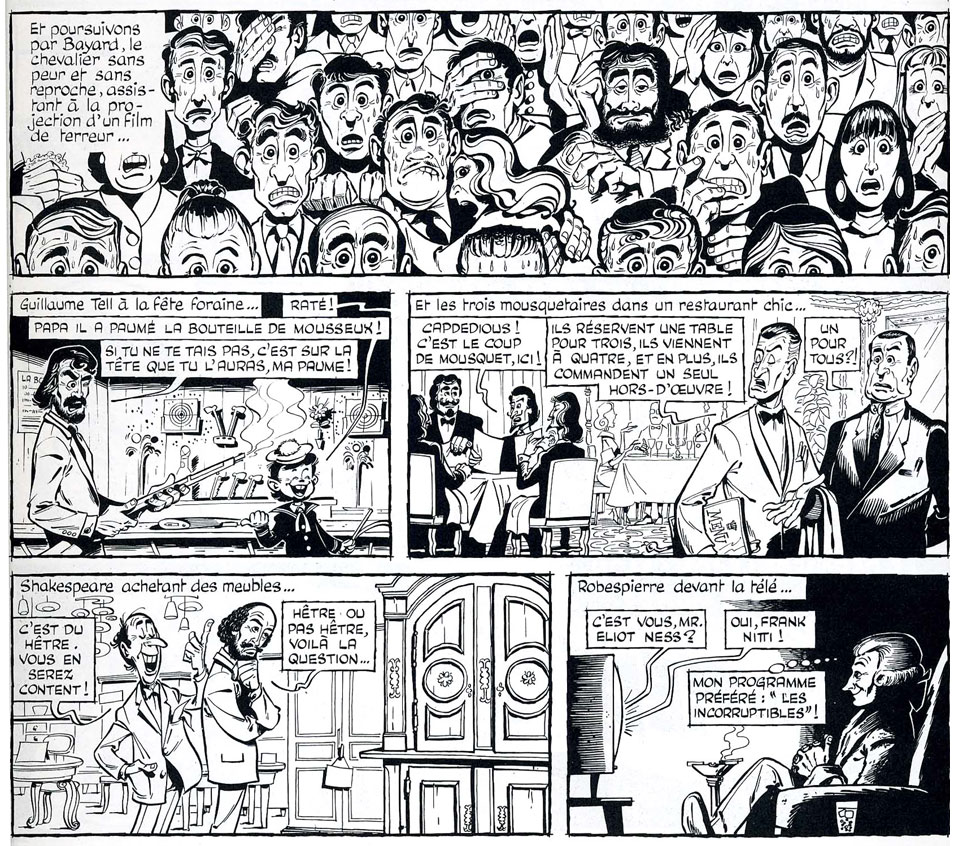

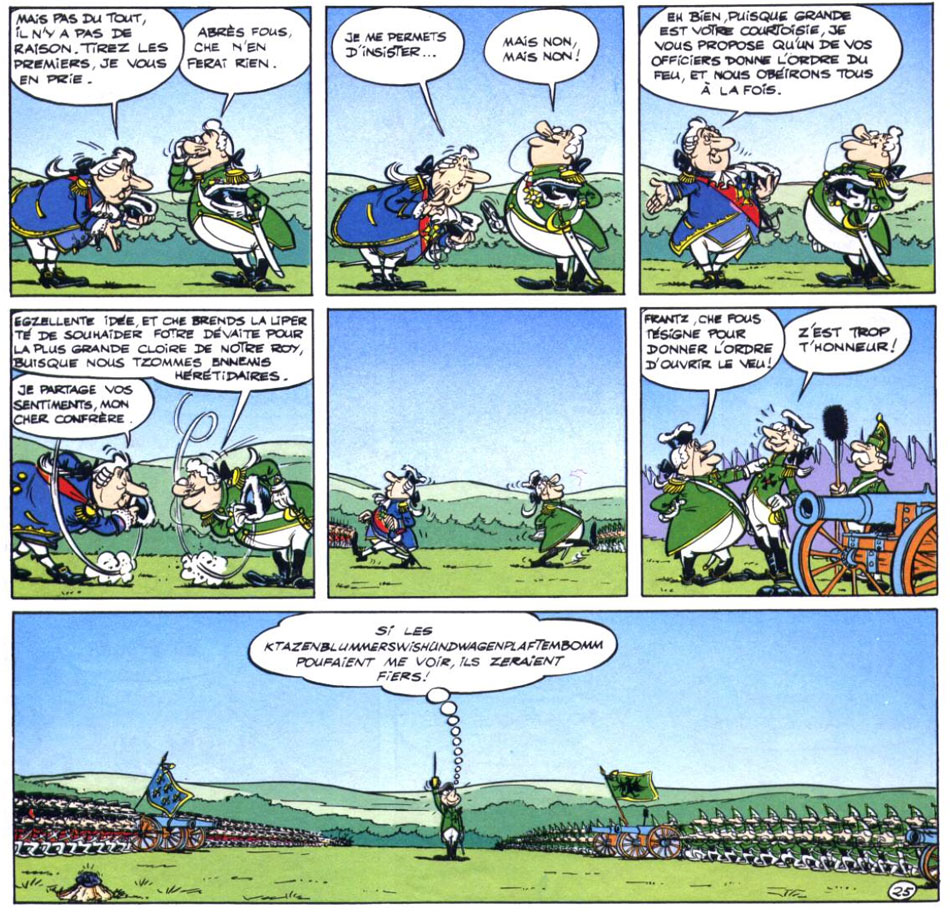

Les Dingodossiers

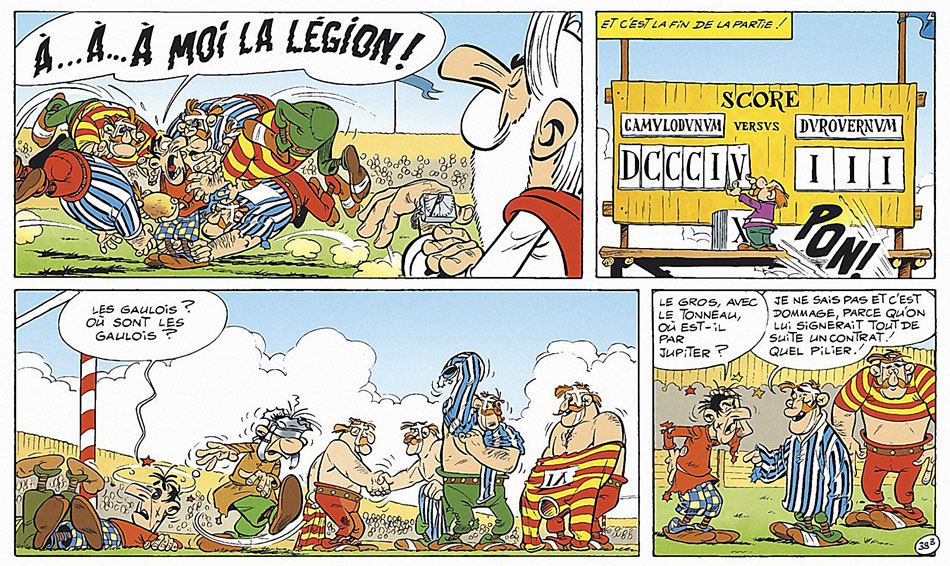

Already in 1962, Goscinny was writing satirical editorial sections like 'Potachologie Illustrée' and 'Ce Qu'il Ne Faut Pas Faire', both illustrated by Cabu. Together with Marcel Gotlib, Goscinny launched the satirical Pilote feature 'Les Dingodossiers' (1965-1967), of which the first episode appeared in issue #292 (27 May 1965). The comic was a funny parody of educational comics, with each episode centering around a question or a subject, usually asked by a little boy named Chaprot. Chaprot's naïvité and rampant spelling errors are very reminiscent of Goscinny and Sempé's other comic series 'Le Petit Nicolas'. Yet the answers the boy receives are equally silly. A wide variety of topics were covered, including space travel, animal life, tourists and the correct way to feed a baby. Goscinny's love of verbal comedy, satire and stereotypes and Gotlib's talent for hilarious characterization and cartoony slapstick proved to be a golden combination. While 'Les Dingodossiers' is still regarded as a classic in French comic history, Goscinny's workload became heavier, and he decided to drop all of his scriptwriting in favor of his three most successful comic series. After he retired from 'Les Dingodossiers' in Pilote issue #423 (30 November 1967), Gotlib continued the series on his own, but out of respect for his former scriptwriter, changed the title into 'Rubrique-à-Brac' (1968-1972).

'Les Dingodossiers', artwork by Gotlib. Various historical characters are found in modern-day situations that poke fun at their historical deeds. Bayard, the "knight without fear" works as assistant-projectionist during horror movies. William Tell is a carnival shooter, but his bad aim is mocked by his son. The Three Musketeers are in a restaurant, where the waiters complain that they "have reserved for three, but four people arrive and they only eat one meal", whereupon the other asks: "One for all?" William Shakespeare considers buying furniture and is guaranteed that a cupboard is pure beech ("hêtre" in French), whereupon Shakespeare quotes from 'Hamlet': "To be(ech) or not to be(eech), that's the question." French politician Maximilian Robespierre (who betrayed the ideals of the French Revolution with his Reign of Terror) watches TV and claims that 'The Untouchables' ('Les Incorruptibles' in French, which translates to 'The Incorruptibles') is his favorite show.

Changing times

Targeting a teenage audience, Pilote had quickly become a serious competitor to the Belgian magazines Spirou and Tintin. Both its satirical humor and realistic drama comics were more daring and since Pilote was French, it didn't need to bow to the demands of the French censorship committee, something that comic magazines imported from Belgium were forced to do. Recognizing Pilote as a serious threat, combined with the changing perception of comics in general, both Spirou and Tintin underwent several editorial and stylistic changes to update their image. During the 1960s and 1970s, both introduced more violent action comics, modern female heroines and more daring humor. Pilote's influence could also be found in the layout and content of the Dutch comic magazine Pep. All in all, Pilote is generally considered the most influential post-war French comic magazine, which played a large role in bringing European comics into adulthood.

Ironically enough, around the same time Tintin and Spirou modernized, Pilote was fighting a battle for modernization of its own. The student protests of May '68 had created an atmosphere where many youngsters felt society ought to break with conventions in favor of more progressive changes. Younger artists in Pilote insisted that the magazine had to move beyond imitating Mad's comedy and instead aim for more anarchic, taboo-breaking comics, like U.S. underground comix and the French magazine Hara-Kiri. For the elder and old-fashioned Goscinny, who just wanted to make a family-friendly magazine, this was out of the question. In general, the new wave of Pilote artists wanted a collective editorial approach and more social security.

On 21 May 1968, the artists gathered in a brasserie at the Rue des Pyramides in Paris. The editors-in-chief Goscinny and Jean-Michel Charlier were invited, and hoped that this less formal location would help lighten the mood. As the discussions became more heated, Jean Giraud called Charlier and advised him not to come. Goscinny was however already on his way and stepped right into the line of fire. Since the May '68 strikes had caused chaos all throughout France, the latest Pilote issues were delayed. When Goscinny was asked about the situation, he made the mistake of honestly admitting that he had no clue when production would be able to restart. This made the artists even more confident that they had to take editorship into their own hands, since their boss apparently was ignorant about the future of their jobs. Their anger was also fed by some Marxist union leaders present in the room, who stood beside the Pilote artists.

From Goscinny's perspective, his employees were simply too naïve and inexperienced to just take over the wheel. Also, he had to defend not only himself, but the entire magazine and its executives on his own. Goscinny left the meeting in severe stress, especially since he considered the artists as friends and colleagues, who now suddenly "turned against him". Indirectly, that fateful afternoon changed the course of his career. A couple of weeks later, he presented a new editorial plan, which stipulated that Pilote was to contain about four to five collectively made news pages. All the artists were expected to be present during weekly gatherings at the office. Personally, he distanced himself from the artist team, leaving most of the communication to his sub-editor, Gérard Pradal.

Still, this new direction had set things in motion that couldn't be stopped. In the early 1970s, Goscinny's relationship with his fellow editor-in-chief soured, when he wanted to remove Charlier's series 'Tanguy et Laverdure' from serialization in Pilote, since it had become too traditional. Charlier then stepped down from his position as literary director, and left Éditions Dargaud altogether. On top of that, Gotlib, Nikita Mandryka and Clarie Bretécher secretly created a more provocative magazine of their own, L'Écho des Savanes (1972), making Goscinny feel even more betrayed. In 1973, he stepped down as editor, and was succeeded by Guy Vidal, who eventually turned Pilote into a monthly. In the following years, several of Pilote's more innovative artists left to start their own magazines, most notably Fluide Glacial and Métal Hurlant. Gotlib, who had a strong creative and amiable friendship with Goscinny, regretted how things had turned out, especially after Goscinny's early death in 1977. He went into therapy for years, battling the guilt.

The infamous 1968 brasserie meeting has become a legendary moment in French comic history, particularly since so little information was available about what happened and what was said. Many rumors and urban legends circulated. In 2019, half a century after the events, Christian Kastelnik set the record straight by releasing a properly researched book about the event: 'René Goscinny et le Brasserie des Copains' (La Déviation, 2019), featuring eyewitness accounts.

Comical exaggeration and toying with expectations in 'Jehan Pistolet Et Le Savant Fou'. Artwork by Albert Uderzo.

Style: narratives and humor

By the mid-1950s, Goscinny had become a towering figure in Franco-Belgian comics. Previously, scriptwriters were novelists, journalists or columnists who supplied comic artists with daily or weekly gags or narratives. Several remained anonymous, because comics had such a low-brow reputation that it might damage their "serious" literary career. Even the credited ones were often expandable and interchangeable. Press and general readers were far more interested in the artists than the comic writers. Goscinny too started out as a mere writer-for-hire, but quickly gained a reputation as a witty humorist. He proved equally swift in one-page gags as short stories and full-blown adventures. Even with series that he hadn't been involved with from the start, like Morris' 'Lucky Luke', Goscinny managed to put his personal stamp on and bring them to a higher level. By the start of the 1960s, he was already in such demand that he could actually live from his profession and refrain from drawing himself. During the first five years as chief editor of his own magazine Pilote, Goscinny kept penning gags and plots for dozens of artists. But in 1965, he eventually reduced his workload to focus on his three best-selling series: 'Asterix', 'Lucky Luke' and 'Iznogoud'.

Goscinny became the first European comic writer to be as well-known and admired as any comic artist. He achieved this by appealing as much to children as to adults. The basic plot of a Goscinny story is straightforward and easy to follow. Goscinny sprinkles the narrative with slapstick violence, hilarious cast interactions and increasingly funnier running gags. Sophisticated wordplay and cultural-historical nods entertain more adult readers too. Some stories delve into quite complicated subjects, like economics (the 'Astérix' story 'Obélix et Co.') or psychology (the 'Lucky Luke' story 'A Cure for the Daltons'). Certain references may go over some readers heads, like the orgy scene in 'Asterix in Switzerland' being a shout-out to the Federico Fellini film 'Fellini: Satyricon' (1969). By the same token, the comedy of certain lines and situations in, for instance, 'Le Petit Nicolas' will be noticed by adults more than children. But Goscinny always kept his stories fun and engaging. In his own opinion, he never had a specific demographic in mind other than "things which, to me, seemed to amuse everyone."

Out of all his comics, 'Astérix' is widely regarded as Goscinny's magnum opus, since he could put all his pet peeves in. It was also a perfect combination of something that could appeal to general audiences and intellectuals alike, while being family friendly, but with multilayered comedy. Ancient Rome is still a large part of the historical curriculum in many schools, familiar through history lessons. Being a dominant culture for four centuries, the Roman Empire also left a strong impact on European present-day language and culture, giving Goscinny a wide playground to make intellectual jokes without fear of alienating those who only have a basic knowledge of the time period. This also explains why 'Astérix' is massively popular in Europe, a continent shaped by ancient Rome, but never quite caught on in parts of the world where the culture never had as strong an impact.

In the 'Lucky Luke' episode 'Rails on the Prairie' (English-language version) a little girl is tasked with offering flowers to a dignitary, but is constantly ignored. Artwork by Morris.

Style: running gags

Goscinny's running gags typically come in two flavors. Some are restricted to one specific story. In the 'Lucky Luke' story 'The 18th Cavalry', a hat salesman complains to an army general that his merchandise has been ruined by Native Americans who shot holes in them. He keeps popping up throughout the tale, asking when and whether he'll receive compensation. Later in the story, the soldiers' fortress is set on fire and everybody tries to douse the flames "with everything that can be used to pour water into". Somebody uses the salesman's hats, remarking "but they're all full of holes", whereupon the furious salesman yells: "Don't blame me!" Other gags barely last a page. In 'Asterix in Belgium', Asterix, Obelix and Vitalstatistix demolish a Roman fortress to impress a Belgian tribe, but the Belgian chieftain only considers it "mildly amusing". An argument breaks out between Vitalstatistix and the Belgian chieftain, while a beaten up Roman legionary joins the debate, siding with Vitalstatistix that the fight was indeed very painful and destructive. However, everybody ignores him. It isn't until he leaves for the Roman camp again and waves goodbye that Astérix finally notices his presence.

Goscinny also used running gags that recur throughout a series, much to the amusement of long-time readers. In 'Astérix', for instance, the Gauls always encounter a group of pirates, whom they beat up and sink their ship. Having learned from all their previous encounters, the pirates are so frightened that they try to flee, but are usually clobbered up anyway. Goscinny sometimes uses variations to this set-up. In some stories, the buccaneers sink their ship by their own hand, as a preventive measure. Other times, they aren't at sea, but to their horror still stumble upon the Gauls. In 'Iznogoud', Iznogoud wants to become "caliph instead of the caliph", but his convoluted schemes invariably fail. It gets to the point that basically everybody in Baghdad is aware of his obsessive plan, except - ironically - the caliph, who still believes all the stories about Iznogoud are pure slander. Readers know that Iznogoud will fail again, but look forward to seeing how he will screw up this time.

Style: fantasy and exaggeration

While the action in his humorous historical series is set in plausible reality, René Goscinny didn't shy away from using fantasy elements. The Gauls in 'Astérix' use a magic potion to defend their village. When people are beaten up, they fly several miles into the air. Lucky Luke's reputation as the man "who shoots faster than his own shadow" is often pulled into the absurd, with cowboys being disarmed in less than a second. In 'Iznogoud', elements from the 'Arabian Nights' fairy tales turn up, like flying carpets and djinns fulfilling wishes. Animals in all of Goscinny's series are often anthropomorphized, though with certain degrees. In 'Astérix', for instance, Obélix' dog Dogmatix can't talk, but Lucky Luke's horse Jolly Jumper and the stupid prison dog Rantanplan in 'Lucky Luke' do converse, although humans can't understand them.

Anachronistic comedy in 'Astérix Chez les Bretons' ('Asterix in Briton', 1966). Artwork by Albert Uderzo.

Style: historical research and references

Goscinny was at his best when writing longer adventures in a historical setting, whether antiquity ('Astérix'), the ancient Middle East ('Iznogoud'), the Golden Age of Piracy ('Jehan Pistolet') or the Far West ('Lucky Luke', 'Oumpah-Pah'). He toyed with elementary knowledge about these specific eras. The things everybody learns about in school, added with imagery, clichés and tropes from costume films, novels, comics, art and advertisements. In 'Lucky Luke', for instance, every western town has an overactive gravedigger and lynch-happy mobs. Native Americans communicate with smoke signals, but make spelling errors. The cavalry rides in to save the day, but are sometimes too late. In 'Astérix', all the Gauls have winged helmets, mustaches, while chieftain Vitalstatistix is carried around on a shield (a real-life Celtic tradition), but due to the stupidity of his servants often falls off, or forgets to duck when leaving a building, bumping against the facade.

While all his historic comics are humorous, Goscinny still documented himself about the time periods to get facts right, as well as to find inspiration for new stories. It helped him create a cartoony, but believable and atmospheric pastiche. Goscinny enjoyed making cultural-historical nods. In 'Asterix the Gladiator', Julius Caesar tells his adoptive son Brutus to applaud along, with the line "Tu quoque, fili" ("You too, my son"), a reference to Shakespeare's play 'Julius Caesar'. Caesar feels irritated about Brutus and thinks he "may get him in trouble one day", a nod to Brutus' later assassination of Caesar. In 'Asterix and the Cauldron', Obelix wins various Roman statuettes, but Asterix dismisses them: "It will take centuries before these things will be worth something." In the 'Lucky Luke' story 'Billy the Kid', Luke meets the real-life historical outlaw Billy the Kid. The infamous gunslinger is portrayed as an obnoxious, infantile brat who terrorizes people by sheer reputation and intimidation.

Anachronistic comedy is a staple too. In 'Astérix in Switzerland', the Gauls go to the 1st century BC equivalent of a petrol station, where their chariot can have its wheels checked, with an oatmeal supply for their horses. The rugby game in 'Asterix in Britain' keeps score by using Roman numerals, while the referee has a tiny sundial on his wrist to watch the time. In 'Iznogoud', Goscinny went absolutely ballistic with anachronisms, ranging from time travel to objects that wouldn't be invented until centuries later, like a jigsaw puzzle.

Two Dutch authors, René van Royen and Sunnya van der Vegt, investigated the historical accuracy of the 'Astérix' universe in three books, published by Bert Bakker: 'Asterix en de Waarheid' ('Asterix and the Truth', 1997), 'Asterix en de Wijde Wereld' ('Asterix and the Wide World', 2002) and 'Asterix en Athene: Op Naar Olympisch Goud!' ('Asterix and Athens. Onward to Olympic Gold!', 2004). They actually came to the conclusion that various objects, customs, architecture and geographical details were depicted far more historically accurate and realistic than one would expect from a humorous comic strip. Tutors shouldn't underestimate the impact 'Astérix' had on modern audiences' general knowledge either. Many schools offer albums translated into Latin or Ancient Greek to help their students master these ancient languages. Nowadays, generations of comics readers are familiar with terms like "druids", "menhirs", "centurions", the Gaulish god Toutatis and Roman names for certain cities and countries (like Lutetia for Paris), all thanks to reading 'Astérix'.

Parody of ancient war customs, in 'Oumpah Pah Contre Foir Malade'. Artwork by Albert Uderzo.

Style: cultural references

Goscinny was a well-read individual and often added cultivated references to his work for like-minded spirits. The muscular Greek slave on the slave market in 'Asterix and the Laurel Wreath' (1971), for instance, strikes several poses that reference famous Ancient Greek sculptures. 'Astérix in Belgium' (1979) closes off with a shout-out to Pieter Bruegel the Elder's painting 'Peasant Wedding', painted by Marcel Uderzo, brother of Albert. When Goscinny wanted to make a 'Lucky Luke' story about real-life Wild West outlaw Jesse James, he was amused by the historical fact that James' brother Frank was a fan of Shakespeare. In the album, 'Jesse James' (1969), Frank therefore constantly quotes lines from famous Shakespearean plays in thematically appropriate situations. In 'Astérix', Goscinny also often used untranslated Latin quotations. Average readers might not understand them, but Latin students and history scholars can. For instance, when the pirates strand on a beach in 'Asterix in Britain', one of them says: "Fluctuat nec mergitur" ("She is rocked by the seas, but doesn't sink"), which is the Latin motto on the Parisian coat of arms.

In addition, Goscinny also made nods to more popular culture. The Corsican chieftain Ocaterinatabellatchitchix in 'Asterix in Corsica' has a name referencing the song 'O Caterina' by Corsican singer Tino Rossi. Various Gauls and Romans in the 'Astérix' comics are physically modelled after film actors (Lino Ventura, Raimu, Laurel & Hardy) or politicians (Jacques Chirac). Several cinema stars also have guest roles in 'Lucky Luke', including David Niven, W.C. Fields and Mae West. Sometimes, these caricatures have a stronger narrative purpose. The Roman prefect in 'Asterix and the Golden Sickle' (1962) is modelled after Charles Laughton, in reference to Laughton's similar role in the Hollywood sandal epic 'Spartacus' (1960). The bounty hunter in the 'Lucky Luke' story 'Chasseur de Primes' (1972) looks like Lee Van Cleef, winking at his role in the western 'For A Few Dollars More' (1965). Other comics are sometimes referenced too. In the 'Iznogoud' story 'Le Tapis Magique' (1973), Captain Haddock from Hergé's 'Tintin' has an unexpected cameo, only to be chased away by Iznogoud who, ironically, hurls very Haddock-esque insults at him, like "bachi-bouzouk".

Wordplay in 'Les Dingodossiers'. Artwork by Gotlib. The tables of multiplication are presented as anthropomorphic tables, who make various puns on expressions with numbers. A man is looking for 'Ornicar', a nod to the mnemonic 'Mais oú est donc Ornicar?' ("But, where is Ornicar then?"), which pupils use to remember the coordinating conjunctions. A louse, ring, pebble, cabbage, knee, teddy bear and owl claim they'll take an "-x", because they are "in plural." The joke is that most plural forms in French end with "-s", but they are exceptions that ought to end in "-x", namely "des poux" ("lice"), "des bijoux" ("jewelry"), "des cailloux" ("pebbles"), "des choux" ("cabbages"), "des genoux" ("knees"), "des joujoux" ("toys") and "des hiboux" ("owls").

Style: verbal comedy

Goscinny was additionally fond of puns and wordplay. He gave cast members and one-time characters names with a hidden pun in them. The Native American tribe in 'Oumpah-Pah', for instance, are named the "Chavachavas", word play on the expression "ça va, ça va" ("everything is fine"). Since many Gaulish chieftains (Vercingetorix, Dumnorix, Ambiorix, Orgetorix) and gods (Albiorix, Caturix) have names with the suffix "-ix", he gave all the Gauls in 'Astérix' pun-based names like Comix, Appendix and Linguistix. Asterix himself is a pun on the word "asterisk". Goscinny observed that many Roman historical figures (Augustus, Tacitus, Marcus Aurelius) and mythological characters (Bacchus, Venus, Romulus & Remus) all have names ending with "-us", thus giving the Romans in 'Astérix' pun-based names like Hotelterminus, Diplodocus and Habeascorpus. Similarly, some of the Roman settings are given names like Aquarium, Linoleum and Postscriptum. In 'Iznogoud', the main characters have pun-based names like Iznogoud ("Is no good"), Dilat Larath ("dilate la rate", meaning "burst into laughter") and Sultan Pullmankar ("Pullman car", a fancy sleeper car for trains). The only main series by Goscinny to remain free from wordplay was 'Lucky Luke', because Morris didn't like puns.

Apart from names, the dialogues in Goscinny's comics also hide wordplay. In 'Astérix and Cléopâtre' (1963), an Egyptian from Alexandria introduces himself with a 12-syllabic sentence, while Getafix informs the others: "C'est un alexandrin" ("This is an Alexandrin", making a pun on both a citizen from Alexandria as well as the verse form "alexandrin"). Other dialogue references historical-cultural quotes. When Astérix duels a big-nose Roman in 'Caesar's Gift' (1977), for instance, he quotes directly from Edmond Rostand's theatrical play 'Cyrano de Bergerac'.

Many of these puns and wordplay aren't always obvious to readers and frequently gave translators a challenge. Some were forced to come up with their own linguistic resolutions or jokes that are more understandable for their target audience. Since Goscinny could speak English and Spanish, he was able to give these specific translators feedback and suggestions. With other languages, he simply let the translated texts be retranslated into French for him, with additional footnotes, so he could get a grasp of how well it matched his original jokes. It was through this method that he discovered that the first West German translation of 'Astérix Chez les Goths' contained political propaganda against East Germany, which he promptly demanded to be removed.

Still, some of Goscinny's wordplay requires a very thorough knowledge of French language and culture. Some foreign translators didn't always spot these double layers, especially when they had to rush out weekly installments for an upcoming magazine issue. As a result, dialogues were sometimes translated too directly. A well-known example are the Dutch translations, which simply kept the main cast members' names the same as in French, not realizing that names like Abraracourcix and Assurancetourix (Vitalstatistix and Cacofonix) were puns. Generations of young Dutch readers have twisted their tongues trying to pronounce these unaltered names. Once Goscinny's stature grew, and translators knew that they had to be attentive to his dialogues, finer translations came about, while reprints came with better linguistic equivalents. In the Dutch reprints of 'Astérix', Abraracourcix and Assurancetourix were eventually renamed Heroix and Kakofonix.

The verbal comedy in 'Astérix' was an influence on 'De Kiekeboes' by Belgian comic artist Merho. Apart from similar linguistic games in dialogues, several characters in Merho's series also have names where their first and last name combine a pun.

Examples of Goscinny's use of stereotypes and wordplay. The Greek Plazadetoros speaks in Greek handwriting. His name is a pun on Plaza de Toros, a bullfighter's arena in Sevilla, Spain. The Briton Faupayélatax is a pun on "faux payé la tax" ("one has to pay taxes"). His remark "Je dis" is a literal translation of the stereotypical British expression "I say". Mouléfix the Belgian is a pun on "moules et frites" ("mussels and fries"), a Belgian dish. He speaks in Walloon slang, which literally translates to: "My name, that is Mouléfix, Belgian." The two Germans Chimeric and Figuralégoric speak in Gothic handwriting. Their names are puns on the words "chimerical" and "figure allégoric" ("allegorical figure"). The Egyptian speaks in hieroglyphs. His name, Courdeténis, means "tennis court."

Style: ethnic comedy

Goscinny also delved into ethnic comedy. The Swiss and Belgians in 'Astérix' speak in the dialect from the French-language regions of these countries. The Britons in 'Asterix in Britain' speak French following English grammar, creating lines like "le magique potion" instead of the correct "le potion magique". The speech balloons of other nationalities are printed in characteristic handwriting: the Egyptians use hieroglyphs, the Goths talk in Gothic type and the Greek use Greek alphabet. Various people behave according to national stereotypes. The Britons are polite and imperturbable, Spanish proud and hot-bakered, Belgians jolly and petulant, Swiss obsessed with punctuality and hygiene. Whenever Astérix travels to another country, Goscinny layered his script with numerous references to things this specific nation is famous for in modern life. In 'Asterix in Switzerland', for instance, these nods range from straightforward winks (cheese, mountaineering, yodeling) to more cultivated references (William Tell, bank secrecy, the World Trade Organization in Geneva). Since these jokes are always done in good fun, foreign readers have always regarded Astérix visiting their country as an honor rather than an insult. In fact, the travel-themed 'Astérix' stories rank among the most popular entries of the series.

In 'Oumpah-Pah' and 'Lucky Luke', Goscinny also used stereotypical depictions based on western folklore. Native Americans have animal-based names, Mexicans take siëstas (even sleeping against a cactus) and laundry owners are aphorism-citing Chinese. In 'Iznogoud', he shows the Middle East as basically an 'Arabian Nights' version of the culture. While they may come across as offensive today, Goscinny merely played around with historical and cultural facts and the way they were simplified in Hollywood media and dime novels. It should also be noticed that these ethnic side characters are more than one-note gimmicks. They all have important parts in the narratives and aren't treated as less or more buffoonish than the white protagonists and antagonists. In several stories, the "villains" are always specific individuals, never a generalized group of people. Even the Romans in 'Astérix' are people the Gauls merely put up with, then actively fight down. It should also be mentioned that Goscinny had experiences being an immigrant himself, as he had lived in Argentina, the USA and France.

Live-action film, radio and TV scriptwriting

During the 1960s, Goscinny also began writing for television and cinema productions. He served as gag man for 'Le Tracassin ou Les Plaisirs de la Ville' (1961), a satirical comedy film by Alex Joffé, and in 1969 he participated in the Europe 1 radio broadcast 'Le Feu de Camp du Dimanche Matin' with Gébé, Fred and Gotlib. Goscinny also worked with producer Pierre Tchernia on the scripts of the feature films 'Le Viager' (1971) - of which the opening credits were animated by Gotlib - and 'Les Gaspards' (1974). Goscinny additionally wrote a comedy script named 'Le Maître du Monde', which he proposed to actor Peter Sellers. While Sellers never replied, the film 'The Pink Panther Strikes Again' (1976) shared notable similarities with Goscinny's script. Goscinny intended to sue, but his early death prevented a trial.

Still from 'The 12 Tasks of Asterix'. The iconic and hilarious "permit A38" scene.

Animation

Another important part of Goscinny's time was dedicated to the animated adaptations of his most famous comic series. In 1965, the Belgian animation company Belvision adapted the very first 'Astérix' story, 'Asterix the Gaul' into an animated feature, directed by Ray Goossens. However, Goscinny and Albert Uderzo weren't consulted beforehand, and by the time they learned about the upcoming film, it was already too late to prevent its premiere. While the film did well at the box office, it was a very literal adaptation of the original comic and so Goscinny and Uderzo stipulated more creative control over Belvision's next 'Astérix' film, 'Astérix and Cleopatra' (1968). Goscinny was well aware that an animated feature required a different approach than a comic, so he removed specific scenes while writing new material taking full advantage of the creative possibilities of cinema. As a result, 'Astérix and Cleopatra' was much better received.

In 1971, Belvision also produced an animated feature based on 'Lucky Luke', featuring an original script by Goscinny, not based on a pre-existing album. The plot, about the rise and fall of a western town, was originally simply titled 'Lucky Luke' at its premier. For its 1980s video release it was retitled to 'Daisy Town'. One of the notable animators on this production was Nic Broca. The picture was a critical and commercial success. In 1983, over a decade after the film's release, the story was adapted into a comic book, drawn by Pascal Dabère from the Dargaud art studio, and included in the official series.