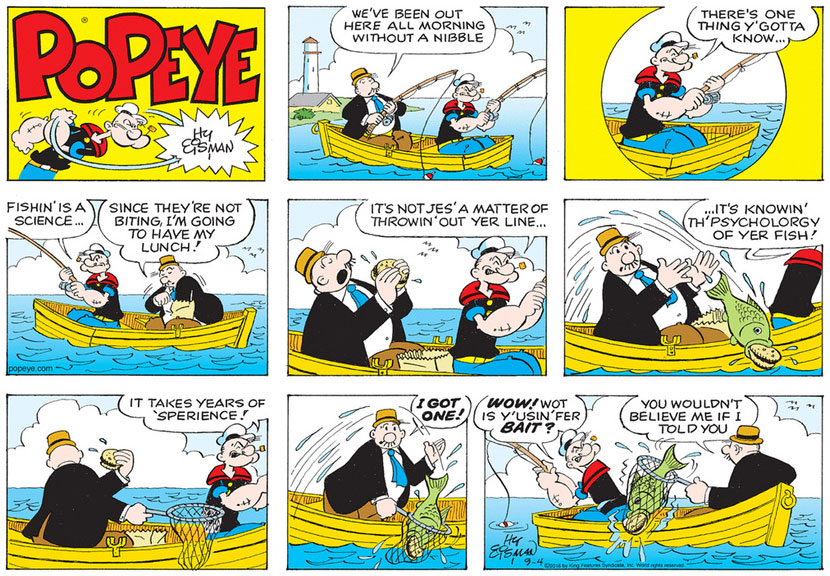

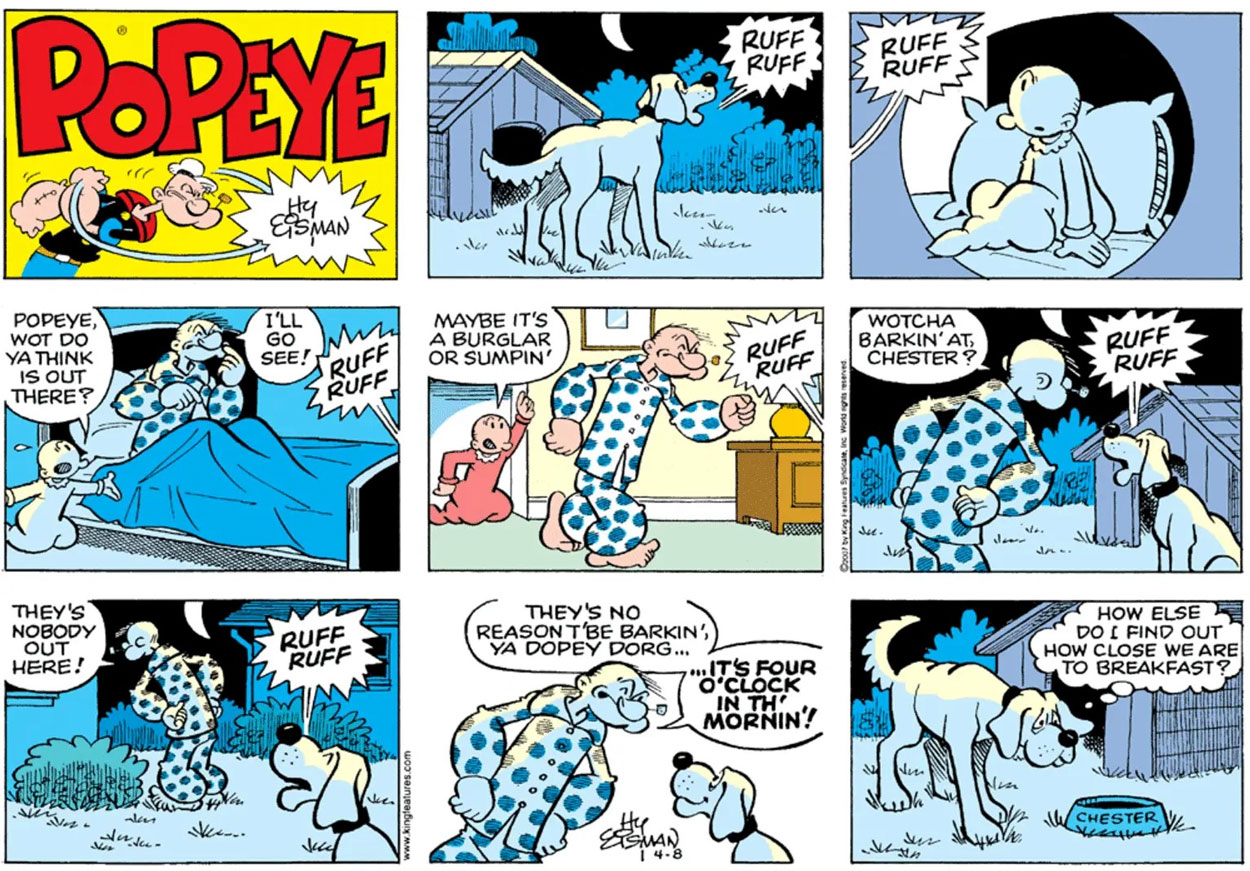

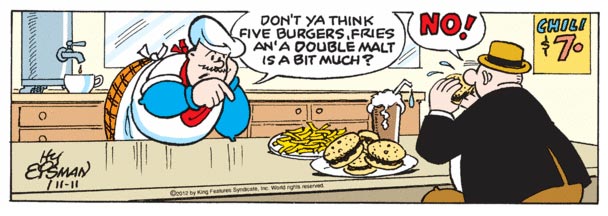

'Popeye' Sunday comic by Hy Eisman.

Hy Eisman was an American comic artist, well-known during his lifetime as a reliable ghost artist. He tackled both newspaper comics and comic books in many different genres. Early in his career, he drew an original comic, 'It Happened in New Jersey!' (1953-1956), featuring factual trivia. Eisman was a prominent ghost artist behind the detective comic 'Kerry Drake' (1957-1960) as well as the gag series 'Bringing Up Father' (1957-1965) and 'Little Iodine' (1965-1983). Contrary to many other anonymous artists, he received more recognition later in his career, working on the humor comics 'The Katzenjammer Kids' (of which he was the final artist, 1986-2006) and 'Popeye' (1994-2022). He enriched the 'Popeye' series by introducing a new character, the seaman's dog Chester. Eisman was also a productive artist for romance comic books by Charlton, Marvel and Archie Comics, while drawing the trendy teenager 'Bunny' (1966-1976) for Harvey Comics. Eisman was additionally a teacher at the Joe Kubert School of Cartoon and Graphic Art (1976-2019).

Early life and career

Hyman Eisman was born in 1927 in Paterson, New Jersey, as the son of Polish-Jewish immigrants. His father was a weaver in Paterson's silk industry. Eisman's parents spoke Yiddish at home, only using Polish whenever they didn't want their offspring to understand their conversations. Eisman didn't learn English until he went to school for the first time, when his mother took the opportunity to master the language alongside him. By contrast, Eisman's father never learned English. In 1932, he lost his job, while Eisman's mother was hospitalized with tuberculosis. Eisman and his older brother stayed with their aunt for a while. One of the tenants in her building was an animator for The Fleischer Brothers and Eisman recalled how magical it felt to see a drawing come to life. Unfortunately, his aunt was affected by the Great Depression and forced to sell their apartment, sending Eisman and his sibling off to the orphanage Daughters of Miriam, where he lived from age five to about ten.

Despite these hard times, Eisman was first exposed to comics while staying at the orphanage. Every Sunday, visitors and sympathizers would bring the children the comic supplements of that day's newspapers. He marvelled at these wonderful and funny stories, especially since they were printed in color, while most other media were in black-and-white. He singled out Percy Crosby, Hal Foster, Chester Gould, Clifford McBride, Alex Raymond, E.C. Segar and Raeburn Van Buren as his favorite artists, deliberately keeping their series as the last ones he would read that day, to end on a high note. He also cut out some comics to keep them. Soon he wanted to become a cartoonist himself. He drew during lessons, but also on blackboards, chairs and walls. Whenever teachers punished him for doodling, they reassured his mother: "He'll grow out of it."

Eventually Eisman's mother returned from the hospital, getting a job as a sewing machine operator, while his father had found work as an elevator operator. Eisman used to joke that his father had literally "5,000 people underneath him". Now old enough to get a job too, Eisman earned his bread as a shoe shiner and newspaper boy, while his brother worked in a wholesale dry goods store.

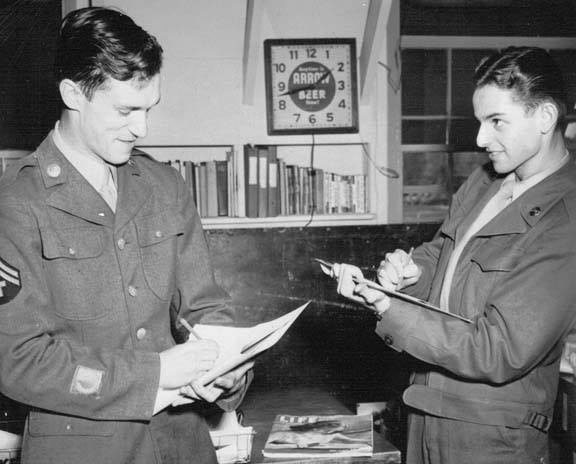

Hugh Hefner and Hy Eisman.

Early comics

Hy Eisman's earliest comics appeared in his high school paper. During World War II, he was drafted, but still in basic training when the war was suddenly over. Instead of seeing combat, he and other trainees were sent to Camp Pickett in Virginia, assigned to a hospital unit. There Eisman livened up the pages of the army newspaper, The Camp Pickett News, originally launched by Bill Mauldin. Eisman's comic was titled 'Parade Rest'. He also designed military health posters. Eisman often collaborated alongside other aspiring cartoonists, including future Playboy editor Hugh Hefner. They had such a close friendship that Eisman had no trouble informing Hefner that his cartoons "weren't any good." After leaving the army, they lost touch, but 50 years later, at the occasion of an army reunion, he sent Hefner a letter, hoping he would come too. Hefner wrote Eisman that he couldn't make it, but replied: "I'm glad one of us made it as a cartoonist and that it was you rather than me, because I wouldn't have had the life I had lived if it had been me!".

Back in civilian life, due to a lack of specific training schools for comics, Eisman went to the Art League's School in the Flatiron Building in Manhattan, New York City, where he studied from 1947 up until 1950. Among his classmates were future cartoonists like Al Kilgore and Frank Thorne. Unfortunately, in the late 1940s and early 1950s, moral guardians led a genuine witch hunt against comics, fed by Fredric Wertham's book 'Seduction of the Innocent' (1954). As a result, many comic publishers went out of business. Eisman recalled that he once showed his portfolio to the editors at Hillman Publications, who liked his work and told him to come back next week. When Eisman returned, he discovered that Hillman had packed up everything and closed down their company during that week. Another time, he went to DC Comics and also had a good job interview, but nothing happened afterwards. Years later, he found out that the man who had talked to him wasn't an editor, publisher or any other executive, but just somebody who operated the elevator! He had been sent to deal with young applicants, since the DC publishers couldn't be bothered to meet everybody. Between 1950 and 1959, Eisman mostly made his money as a freelance greeting card designer for the Fuld Company. Although they were satisfied with his work and offered him a steady job, Eisman still wanted to become a comic artist first and foremost, so he declined the offer. Yet as a greeting card designer, he learned valuable skills on how to design fonts and display lettering.

Start in comic books

Despite the difficult times for the medium, Eisman made his modest comic book debut in the early 1950s. According to the Grand Comics Database, he provided the cover illustration for the Spring 1950 issue of the 'Katzenjammer Kids' comic book by Better Publications, and in the following year created a funny story for Harvey's 'Junior Funnies'. He also appeared in horror/sci-fi titles like Better's 'Lost Worlds' as well as 'Out of the Night' by the American Comics Group (ACG). In 1955, Eisman became a member of the National Cartoonists Society, where he met all his heroes and established more professional contacts. From 1956 on, through his former classmate Frank Thorne, he got a job at Western Publishing, assigned to draw comic book covers and stories based on Bill Holman's humorous comic character 'Smokey Stover'. He went through great effort to mimic Holman's graphic style, using model sheets for study, even acquiring the same kind of pen and ink Holman used. Eisman attributed his success as a ghost artist to these methods, which he kept on throughout his long career.

'The Ghostly Patrol' (Adventures into the Unknown #152, October-November 1964).

In the following decades, Eisman continued to draw for Western Publishing/Gold Key on comic books based on the mystery TV series 'The Twilight Zone' (1965, 1972), the sitcom 'The Munsters' (1966-1967), Hanna-Barbera's cat-and-mouse duo 'Tom & Jerry' (1976-1977), Friz Freleng's cat-and-canary duo 'Tweety & Sylvester' (1975-1982) and classics like Ernie Bushmiller's 'Nancy' (1961) and Marge's 'Little Lulu' (1983-1984). Through Kurt Schaffenberger, he was also hired by the American Comics Group, drawing stories for their fantasy and mystery titles, like 'Adventures into the Unknown' (1964), 'Forbidden Worlds' (1956, 1964-1966) and 'Unknown Worlds' (1965-1966).

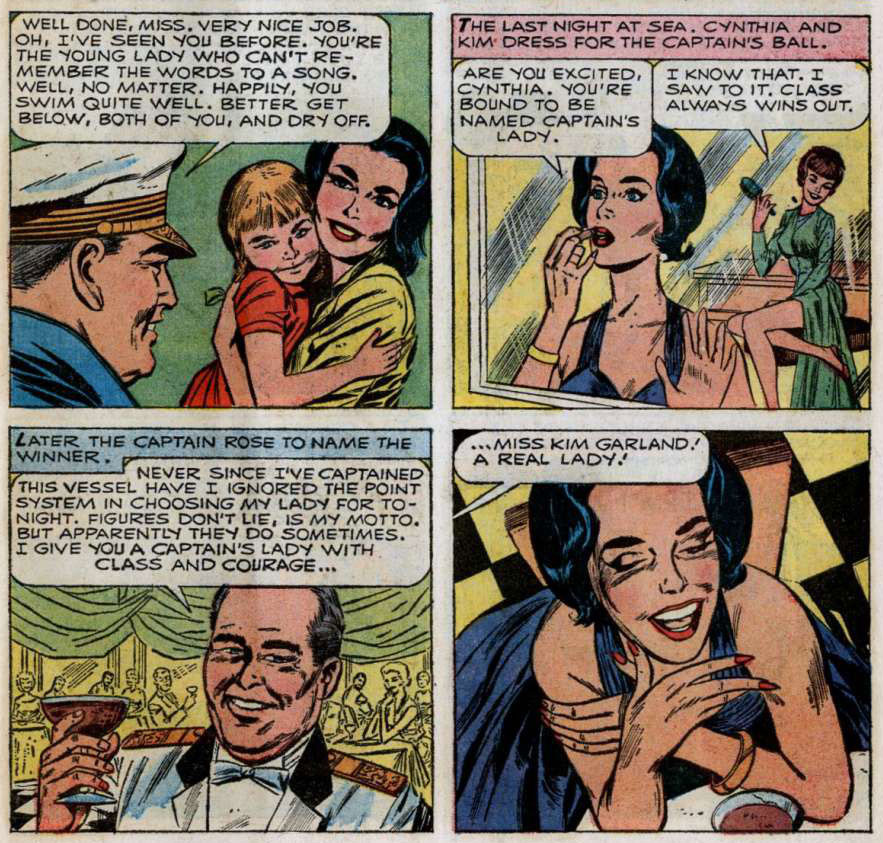

Story for 'Private Secretary' #1 (December 1962), featuring the panel (the fourth) that inspired Roy Lichtenstein's 'Girl in Window'.

Romance comics

Eisman was also a prolific romance comic artist, often collaborating with inker Vince Colletta for Charlton and Marvel Comics. He praised Colletta for being able to ink artwork in such a way that you couldn't tell it was drawn by somebody else. Between 1960 and 1964, Eisman estimated to have drawn about 1,635 pages of love stories. Some also appeared in Dell Publishing's short-lived magazine Private Secretary (1962-1963), of which only two issues appeared. One panel from an untitled story by Eisman in the first issue was later used by pop art painter Roy Lichtenstein (1923-1997) for his painting 'Girl in Window' (1963). In the early 2020s, Eisman found out about this "borrowing" through Rian Hughes' research project 'The Image Duplicator', where he tracked down the exact panels copied by Lichtenstein for his paintings. Eisman had already been critical of Lichtenstein before, since his comic strip-inspired artwork was close to plagiarism, without crediting or financially compensating the original artists. But now it became personal: "It's called stealing. I worked like a dog on this stupid page and this guy has 20 million dollars to show for it. If it wasn't so tragic, it would be [funny]." He recalled that he was only paid around 4 dollars by the magazine at the time. Eisman also commented on the situation in David Barsalou's documentary 'WHAAM! BLAM! Roy Lichtenstein and the Art of Appropriation' (2023), specifically debating Lichtenstein's legacy as either a "plagiarist" or a mere "appropriator".

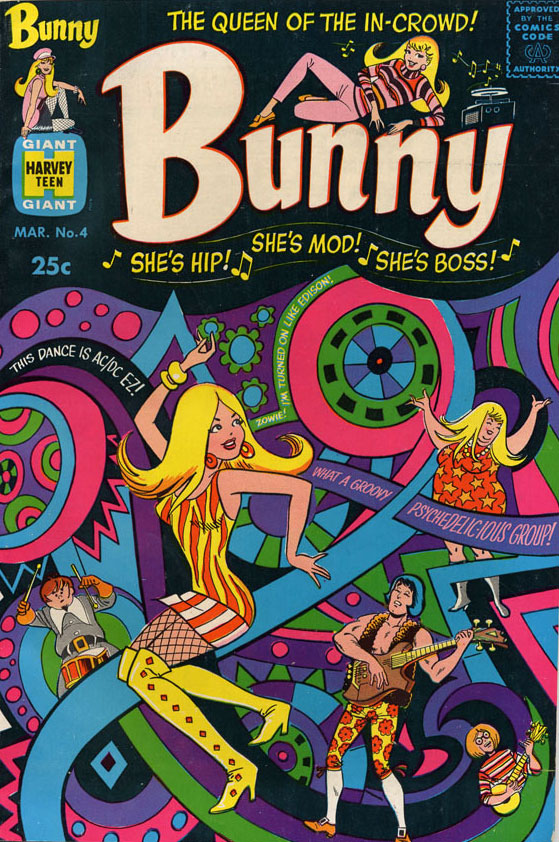

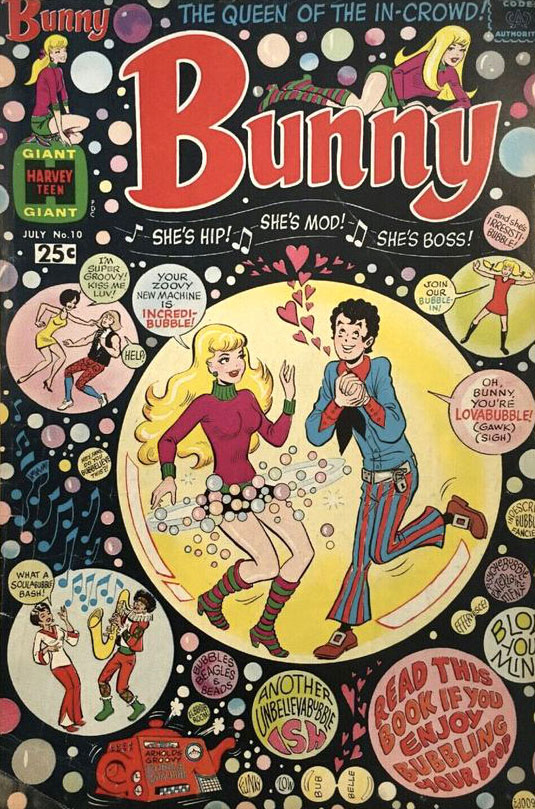

Covers for Bunny #4 (March 1968) and #10 (July 1969).

Bunny and other teenage comics

Between December 1966 and September 1971, Eisman drew the 'Bunny' comic for Harvey Comics. Originally intended as a comic based on a toy doll, Bunny Ball, the deal with this company eventually fell through. Harvey Comics nevertheless decided to launch the series anyway, but under a different title: 'Bunny'. The title character was remodelled into a teenage blonde. Nicknamed "the Queen of the "In" Crowd", Bunny uses words like "zoovy" and "yvoorg" ("groovy" spelled backwards) and is very interested in fashion, pop music and teen culture in general. Her steady boyfriend is named Frederick. Her arch rival is the black-haired Esmeralda, who is secretly in love with Felix, a motorcycle policeman. Another recurring cast member is Bunny's little sister Honey, who also received a spin-off comic.

Scripted by Warren Harvey, 'Bunny' was an obvious attempt to mimic the success of Bob Montana's 'Archie Comics', but with a more timely approach, delving into hippie culture. Eisman drew the series for five years, creating many eye-catching psychedelic covers in the process. Other artists who drew for the 'Bunny' comic books were Sol Brodsky, Warren Kremer, Howard Post and Henry Scarpelli. For readers nostalgic for late 1960s pop culture, 'Bunny' is a treasure trove. People who love campy comedy can appreciate the series too, since the writers and artists, like Eisman, were already in their forties when they made this series and obviously out of touch with 1960s teen culture. Their attempts to be "in" with it are so forced, superficial and badly researched that it makes 'Bunny' unintentionally funny and a time document of how the elder generation viewed the 1960s juvenile subculture.

Also for Harvey Comics, Eisman drew stories featuring Chic Young's 'Blondie', assisting Paul Fung Jr.. Between 1984 and 1991, Eisman returned to comic books and collaborated with inker Vince Colletta again on stories for Archie Publications. He not only drew for the title comic 'Archie Comics', but also the many spin-off series, like 'Archie and Me', 'Katy Keene', 'Mr. Weatherbee' and 'Veronica'.

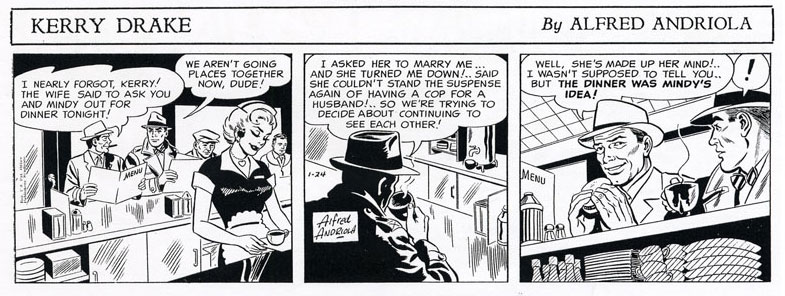

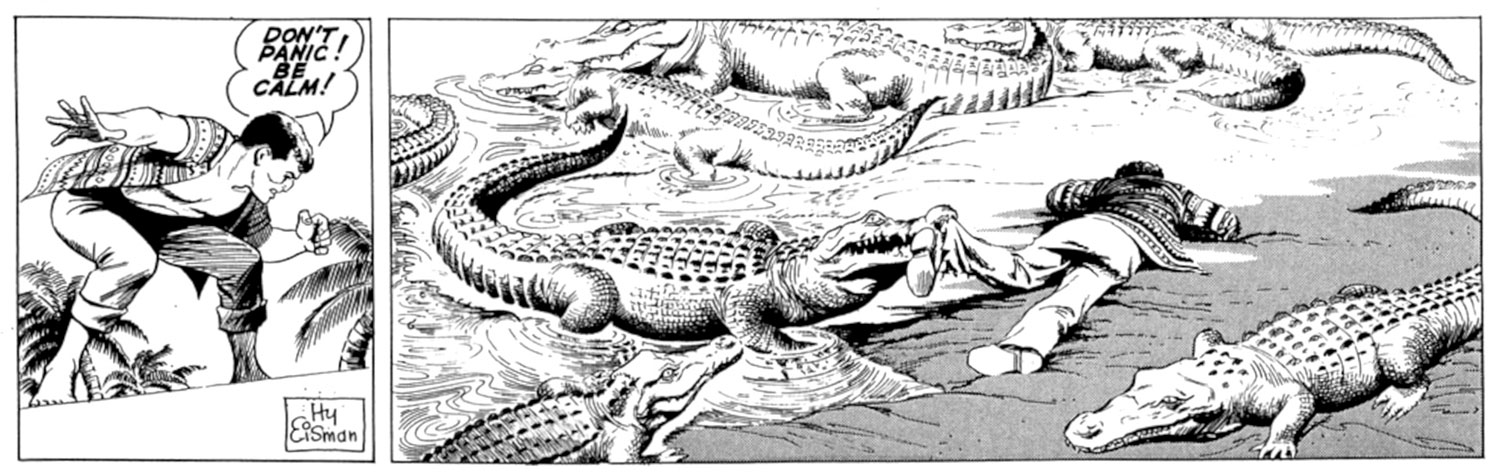

'Kerry Drake' comic strip by Hy Eisman, though credited to Alfred Andriola (24 January 1958).

Kerry Drake

Although he had an impressive track record in comic books, Eisman had an equally fruitful career in newspaper comics, again working mostly as an anonymous ghost artist. In 1952, at the start of his career, Eisman was re-reading Martin Sheridan's informative book 'Comics and Their Creators' over and over. He came across a line stating Alfred Andriola was such a nice comic artist that he never turned down a job interview. Eisman looked up his number in the telephone book, called him and made an appointment. As a test, Andriola asked Eisman to draw a whole week's worth of daily 'Kerry Drake' comic strips for the Publishers Syndicate. At first, Eisman was ecstatic, until it dawned on him that there was still no guarantee that his artwork would be good enough. Indeed, it took him two weeks to finish seven days of comic strips, while not doing any graphic research. Andriola was kind about it, saying he wasn't quite ready yet, but nevertheless paid him for his efforts. He also cleaned up some of the pages, so some could be published after all. It wasn't until 1957, when he and Andriola met again, that his artwork finally met the cartoonist's standards. Until 1959, Eisman ghosted 'Kerry Drake', so Andriola could focus on a new comic series 'It's Me, Dilly' (1957-1960). However, this series never quite caught on, so Andriola eventually dropped this series and picked up the pencil again for 'Kerry Drake'.

It Happened in New Jersey!

While working as a greeting card designer for The Fuld Company, Eisman managed to launch his very first cartoon feature, 'It Happened in New Jersey!' (1953-1956) in the New Jersey News, at the time the largest paper in New Jersey. The comic was inspired by Robert L. Ripley's 'Believe It Or Not' and featured facts and trivia about events and people in association with New Jersey, visualized with drawings. Having learned from his test experience with 'Kerry Drake', Eisman now worked hard to provide the necessary research and reach his deadlines. He learned a lot about the professional side of drawing comics, especially since he had been foolish enough to be put under a lowly-paid exclusivity contract with the New Jersey News, which meant he couldn't syndicate his comic elsewhere.

'Bringing Up Father' strip of 31 December 1960.

Bringing Up Father

Between 1958 and 1965, Eisman ghosted daily gags of 'Bringing Up Father' for King Features Syndicate and became good friends with the then-current artist Vernon Van Atta Greene and his family. Eisman remembered it was quite a challenge to imitate Greene's artwork, since he didn't have a character model sheet. He noticed that the hands of the protagonist Jiggs were drawn in a very specific way readers would pay attention to, so he tried to imitate this as perfectly as possible. When in 1965 Greene was diagnosed with cancer, Eisman basically took over the series in secret, since Greene feared he would lose his job if the syndicate found out he no longer drew it personally. To keep up the facade, he let Greene put his signature on the finished pages, even when he was already hospitalized. Eventually his wife gave Eisman permission to just imitate her husband's handwriting. Greene died in June 1965. In a funny anecdote, his widow once introduced Eisman to a minister, introducing him as "Vern's ghost", then walked away, leaving it to him to explain her macabre description.

While King Features asked Eisman to continue the daily 'Bringing Up Father', the cartoonist refused, because the months before Greene's passing had been so emotionally difficult. Now that his good friend was gone, it didn't feel right to carry on the series on without him and so 'Bringing Up Father' was continued by another artist, Hal Campagna.

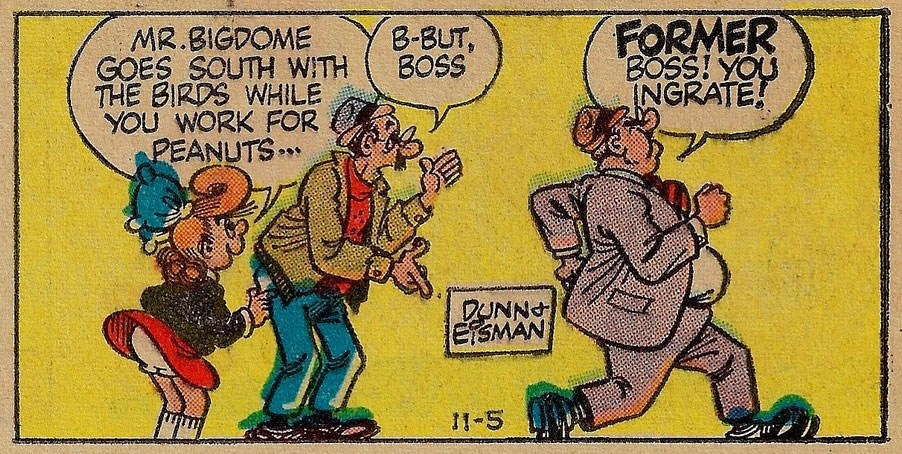

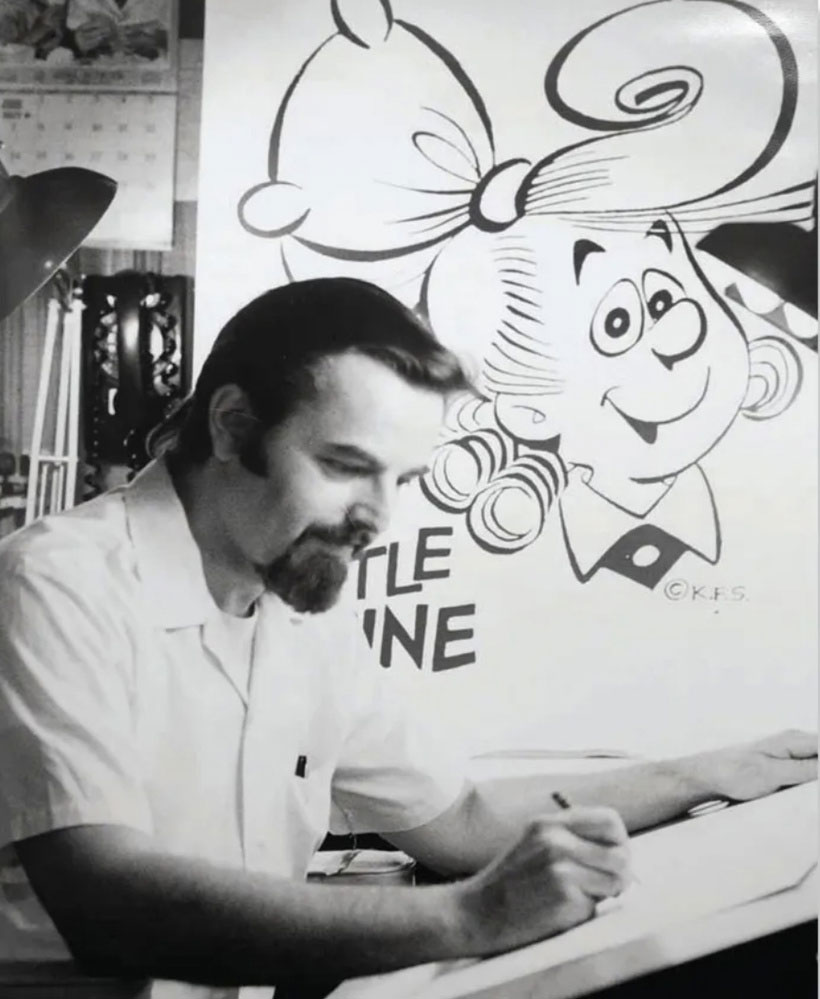

'Little Iodine' (5 November 1972).

Little Iodine

Between 10 September 1967 and 14 August 1983, Eisman continued Jimmy Hatlo's gag comic 'Little Iodine'. Hatlo had passed away in 1963 and since then the gags starring the little girl Iodine had been scripted by Bob Dunn and drawn by Al Scaduto. Sylvan Byck, editor for King Features, wanted to diminish some of Scaduto's workload and contacted Eisman. Hearing that his name would be mentioned in the title credit, Eisman accepted and succeeded Scaduto in drawing the Sunday pages of 'Little Iodine', working together with Dunn on the series until its final episode appeared in print in 1983. In hindsight, Eisman said that it was far more important to him that his name was printed next to his work than what he would be paid for it. Because, once his name appeared in the byline, he ceased to be anonymous and received more notability.

Additional cartooning jobs

In 1960, Eisman drew gag cartoons for the New Jersey Bell Telephone. In 1963, and again in 1965-1966, he also ghosted Sunday episodes of 'Mutt & Jeff', when Al Smith was the main artist. In addition, Eisman made illustrations and posters for J.J. Little and Ives (1956) and N.J. Bell (1960), while providing cartoons for Planned Communications services and public relations media (1966-1971), who ran them in various trade journals and industry newsletters. By 1980, Eisman was designing Japanese toys and stationery.

The Katzenjammer Kids

In 1986, Eisman was given the opportunity of either continuing the classic newspaper comic 'The Katzenjammer Kids' (originally created by Rudolph Dirks), or E.C. Segar's equally iconic 'Popeye'. Eisman chose 'The Katzenjammer Kids', succeeding Angelo DeCesare in drawing the shenanigans of Hans, Fritz, Die Mamma, Der Captain and Der Inspektor for another 30 years.

On 1 January 2006, 'The Katzenjammer Kids' was discontinued after an almost uninterrupted 109 years-run. Nevertheless, at the time there was barely any media attention for the conclusion of the longest-running newspaper comic in history, presumably because King Features Syndicate kept circulating reprints. It took until 2015 before comics researcher D.D. Degg discovered that the series had apparently stopped printing new material for almost nine years. Together with fellow comics historian Michael Tisserand, they contacted Eisman, who indeed confirmed the sad news.

'Popeye' strip by Hy Eisman, featuring his creation, Chester the dog.

Popeye

On a Friday afternoon in September 1994, Eisman was called by his King Features editors and asked whether he could make a 'Popeye' comic before Monday, so it could be used on that week's Sunday. Eisman was not informed about the syndicate's motivations. Only later he found out that the then-current 'Popeye' artist Bud Sagendorf was struggling with his health and falling behind on his deadlines. When King Features phoned Eisman, they only had five weeks left before the next new episode had to appear. A few years earlier, Eisman would have rejoiced on being asked to continue 'Popeye', but the timing wasn't perfect. His wife had been diagnosed with cancer in 1993 and was undergoing painful treatments. He wanted to turn down the offer, but she insisted on him taking the assignment. Since she had always told him to follow his dreams rather than only go for lucrative offers, he agreed to continue the Sunday comics of 'Popeye'. A month later, Sagendorf passed away. Eisman's wife died in October 1997.

For almost 28 years, Hy Eisman drew the Sunday adventures of 'Popeye', colorized by Jim Keefe. Since he was used to drawing people with correct anatomy, he remodelled the characters. Interviewed by Larry Yudelson (Jewish Standard, 20 December 2018), Eisman reflected: "My stuff has slowly become more illustrative, slightly less cartoony. It's very hard to draw badly if you know anatomy. I eventually started changing the proportions to make it more normal. Someone complained I'm drawing badly. They want that old-time look." Eisman toned down the violence and also stopped using the character of Geezil, since he was a stereotypical Jewish immigrant. Even though both 'Popeye' creator E.C. Segar and Eisman himself were Jewish, he felt the character had become outdated. He only gave him one more cameo in 2004, to celebrate Popeye's 75th anniversary. Eisman enriched the cast with new characters too, like Chester, Popeye's dog. He named the pet after Chester, Illinois, where Segar was born. On 10 September 2019, Popeye's dog Chester and his other dogs Fido and Snits received a sculpture in Chester, Illinois, as part of the "Popeye Character Trail".

On 3 June 2022, Eisman retired from 'Popeye' and was succeeded by R.K. Milholland.

'Popeye'.

Teaching career

In September 1976, Eisman became a teacher at the Joe Kubert School of Cartoon and Graphic Art. He had to modernize himself to be up to date with the latest drawing and inking techniques. Ric Estrada also gave him some didactic tips, like not showing your own artwork to pupils, because "it's like asking for a bullet in the back of the neck." Never forgetting his own struggles to make it in the industry, he made an effort to take third-year students to the offices of DC, Marvel and Archie Comics, where they could actually talk with and show their work to professional artists. But it sometimes saddened him that many didn't realize how lucky they were to be given this golden opportunity. As the years passed, Eisman also noticed that his students became less familiar with newspaper comics and often had to bring papers to the classroom to show them examples of what he was referring to. Eventually, he was asked to specifically teach the art of lettering, but many pupils made it perfectly clear that they would rather "pump gas" than ever be bothered to do this kind of task. From the late 1990s on, he noticed that many inevitably asked him whether the assignments he gave them "could also be done on a computer". The very idea of research or adding your own unique touch to it seemed alien to them. As a result, many used the same computer programs to create their comics and picked out the very first photographs on Google Images whenever they needed something to draw, leading to a very monotonous, almost mechanical approach, as Eisman observed, interviewed by Bryan Stroud (23 January 2019).

Yet, there were still many who thanked Eisman for the valuable skills and lessons he taught them, even people originally resistant against his "old-fashioned" methods. He recalled that he could even spark their interest in "old cartoonists of the past", like Hal Foster, by making them pay attention to Foster's skills, which were all done by hand. One of his students was so impressed with Alex Raymond that he went to interview Raymond's relatives and published a book about the artist. Among Eisman's students who became notable names in the comics industry were Terry Beatty, Jan Duursema, Jim Keefe, Tom Mandrake, R.K. Milholland, Fernando Ruiz, Timothy Truman and Rick Veitch. Likewise, Eisman's own working methods also improved. Interviewed by Bryan Stroud (23 January 2019), he said that, before he got into teaching, he used to spread his comics work over two days, taking the first day to draw everything and the second to ink it. As a teacher, he had to speed up his working process and was pleasantly surprised that he could whip out these comic pages in one full day, instead of two.

In May 2019, at age 92, Eisman retired from his teaching activities.

Recognition

In 1975, Hy Eisman received the National Cartoonists Society's Award for "Best Humor Comic Book Cartoonist", more specifically for his 'Nancy' comics. They honored him again on 29 April 1984, this time for his work on 'Little Lulu' (Gold Key Comics). Funny enough, NBC contacted him for a TV interview afterwards under the false impression that he had been honored with a Reuben Award. When he told them the truth, they went quiet for a few seconds, then still decided to interview him. Since Eisman actually didn't do much for 'Little Lulu' any longer, he consulted his editor Walt Green at Gold Key Comics, who informed him that he'd better make the most of it, since Gold Key was actually closing down their comics production at that very moment. Insistent on making a good impression, Eisman and his wife cleaned up their house, only to hear that NBC canceled the interview afterwards.

In 2019, Eisman received the Milton Caniff Lifetime Achievement Award.

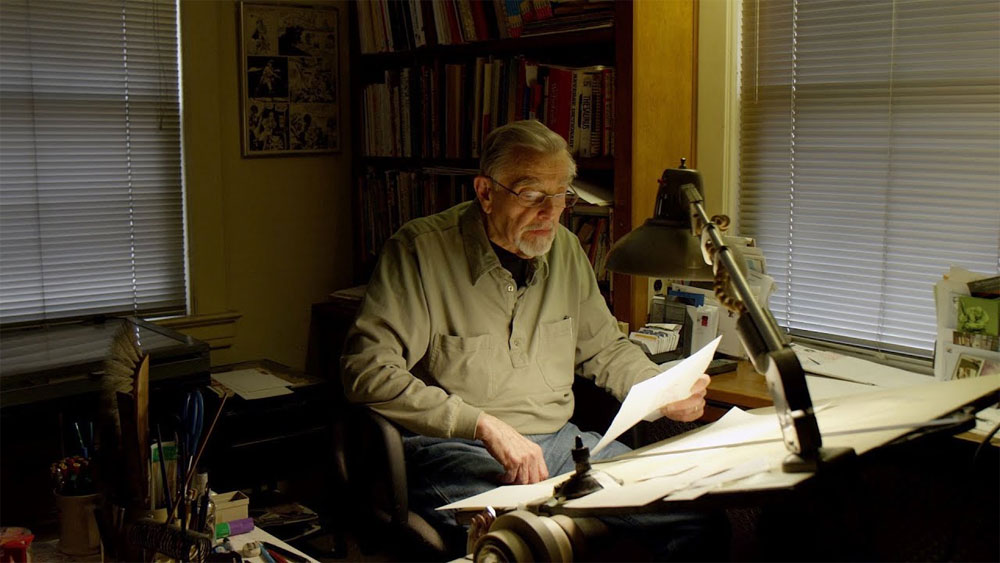

Still from the proposed 2013 documentary 'Hy Eisman: A Life in Comics' by Marco Cutrone and Vincent Zambrano.

Final years, death and legacy

Between 1994 and 1997, Eisman took care of his ailing wife, who had terminal cancer, while simultaneously drawing the series 'Popeye' and 'Katzenjammer Kids' each week and teaching at the Joe Kubert School. It was a physically and emotionally exhausting ordeal, but he started to understand why his wife was so insistent that he kept up his workload: it offered him some essential distraction, especially when she eventually passed away and left a void behind. To avoid falling into depression, Eisman went to a support group, who handed out assignments to their patients. One was starting a conversation with somebody you didn't know. Eisman went to a local library, where he chatted with a woman who turned out to be a managing editor for a publishing company. A relationship blossomed and in 2004 they married.

While Eisman had a lifelong reputation as an excellent and reliable ghost artist, he sometimes had mixed feelings about it. Once he drew several episodes for a colleague, under the impression that he was doing him a favor. But as it turned out, the syndicate had actually commissioned Eisman to draw this specific comic to prove to the artist he thought he helped that he was expendable, thus pushing back against a request for higher pay.

Another time, Eisman was insulted by a critic who nicknamed him "the poor man's Tex Blaisdell". But he cheered up again when Blaisdell referred to himself as "the rich man's Hy Eisman." Reflecting on his long career, Eisman never set out to just draw other artists' creations, but that was the path his life had taken. He remained humble about the supposed stigma: "When you come down to it, it's really just ego. I was always happy to be drawing." Though he also pointed out that, contrary to the hundreds of other ghost artists out there, he was never a real anonymous assistant. His name was known well-enough in the industry to frequently receive assignments. He was regularly interviewed and even received awards. Eisman also prided himself that he was one of the last in a long line of cartoonists who actually kept these long-term characters alive.

A true cartooning veteran, Eisman continued to work until retiring from the 'Popeye' strip at age 95. He died three years later, on his 98th birthday.

'Joe Panther' (unpublished strip).

Non-published comics

Throughout his career, Eisman made a few attempts at launching comics that eventually never came to fruition. In 1960, he and writer Kelly Masters (under the pseudonym Zachary Mell) developed a comic titled 'Joe Panther', based on Masters' young adult novel of the same name. He had earlier considered contacting Lank Leonard to draw it, but his assistant Morris Weiss brought Eisman to his attention, whom he knew was looking for work. For three years, 'Joe Panther' was rejected by almost every syndicate. Most felt an adventure comic about a Seminole Native American like Joe Panther wouldn't be popular with readers. Only United Features showed interest, but would only buy it on the basis of a standard contract, which meant that they would be paid by the amount of papers willing to carry it and how far-reaching the distribution would be. Eisman had heard that Charles M. Schulz was once in a similar situation, waiting 19 months before his comic was sold and so being reduced to living on a couch in Mort Walker's house throughout that period. As such, they predicted that, in these circumstances, it might take months before they would earn something. And even if their series caught on, United Features would take 50 percent of their earnings. So eventually, they gave up their plans. Still, 'Joe Panther' eventually received a film adaptation in 1976. Eisman felt many scenes looked as if they had used his comics as storyboards.

In 1965, Eisman was commissioned to make a newspaper comic based on the animated TV series 'Underdog', but although he was paid for his sample pages, the comic was never launched. In 1973, Eisman also made a comic book based on Bud Blake's 'Tiger', intended for Charlton Comics, but the book was never published.