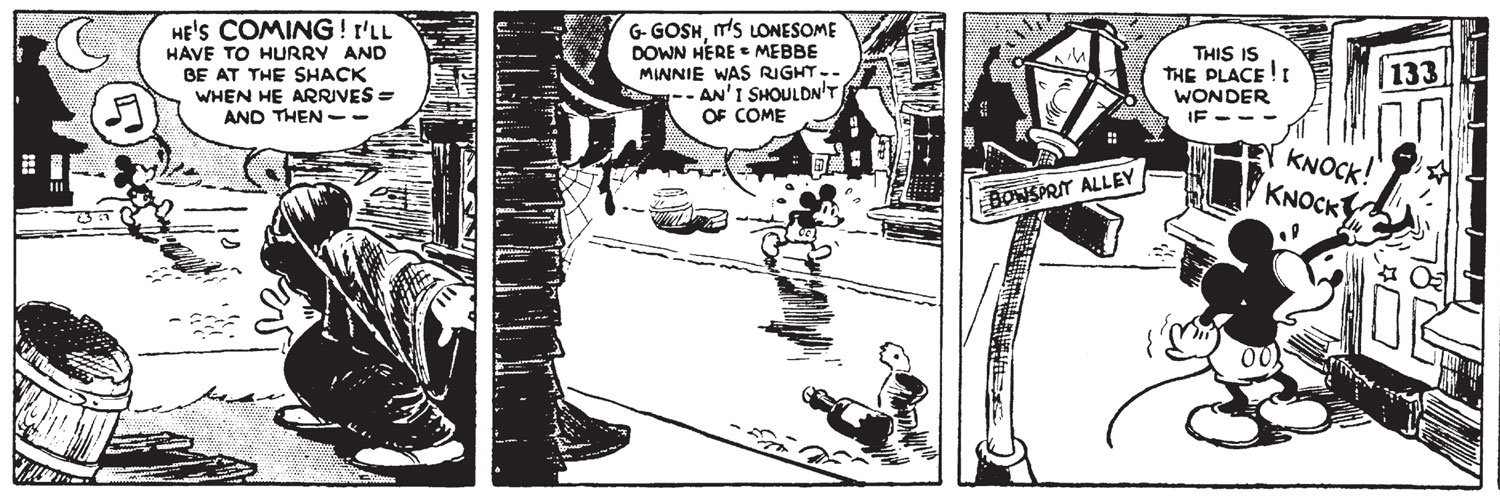

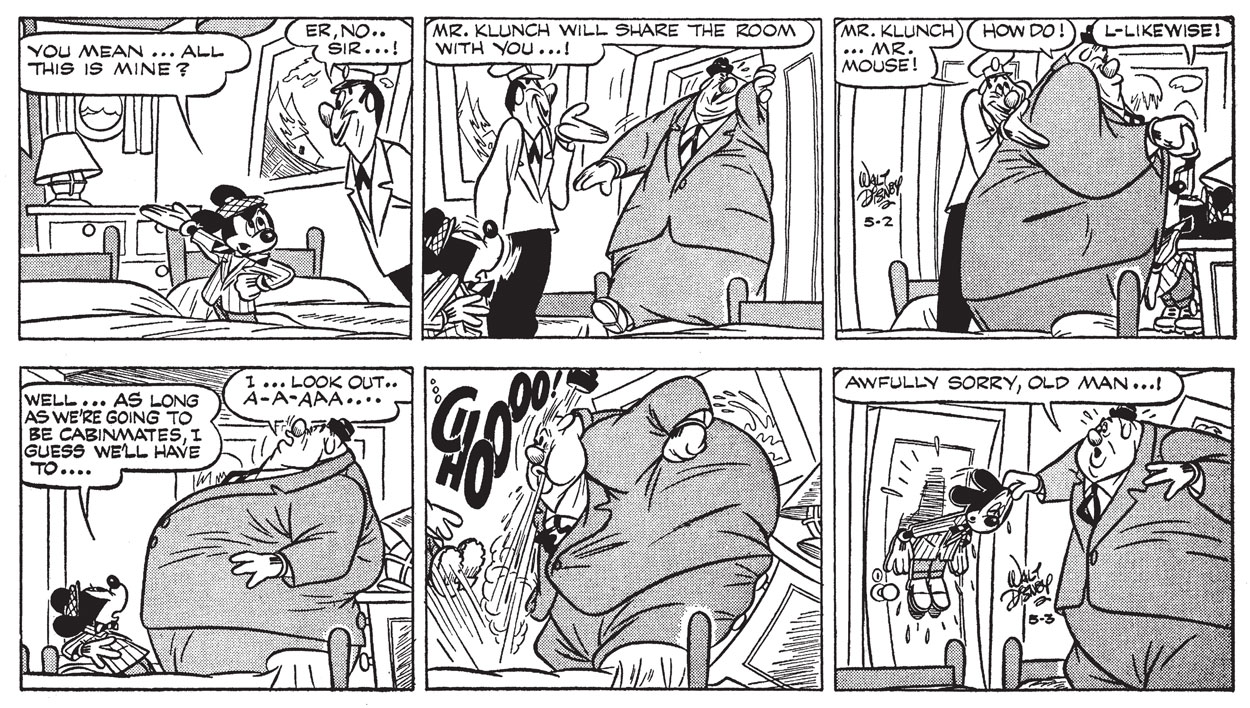

'Mickey Mouse '(16 February 1946) - © Disney.

Floyd Gottfredson is widely regarded as the most legendary and influential 'Mickey Mouse' comic artist, who set the standard for many future Disney comic creators. Contrary to popular thought, he wasn't the first artist of the 'Mickey Mouse' comics. However, still during the mouse's debut year as a comic character, Gottfredson took over Walt Disney and Ub Iwerks's big-eared star and wrote and drew his newspaper adventures for more than 45 years. During his run, Gottfredson developed Mickey into a fully fledged comic character, able to carry both gags and longer adventure stories. He also created several side characters that are still used in many later Disney comic stories, including police officer Chief O'Hara, the cloaked villain The Phantom Blot and the mysterious creature Eega Beeva. Together with Carl Barks, he remains one of the most influential and revered Disney comic artists, but Gottfredson's importance goes beyond Disney. He had a profound impact on humor comics in general, and funny animal strips in particular, proving that with high quality writing and artwork a comic spin-off of a popular cartoon character can outgrow its source material.

Early life and career

Born in 1905 in a railway station in Kaysville, Utah, Arthur Floyd Gottfredson grew up in the small town of Siggud, 180 miles south of Salt Lake City. As a youngster, he was interested in comics like George Herriman's 'Krazy Kat', Billy DeBeck's 'Barney Google' and Walter Hoban's 'Jerry on the Job'. He also enjoyed boys' adventure books by Horatio Alger and detective stories. At age eleven, the boy accidentally shot himself in the arm while playing with a gun. It took nine operations to repair the damaged limb. While he had to stay at home to recover, Gottfredson picked up drawing. Because he had lost most of the flexibility of his hand, he learned how to operate pencils by moving his entire arm. To improve his skills, he took correspondence courses in art from the London School, and from the Federal Schools of Illustrating and Cartooning. Gottfredson's first job was as a projectionist and advertising artist for a small movie theater chain. He drew his first cartoons for the automobile journal Contact, the local newspaper the Salt Lake City Telegram and for the Farm Bureau magazine The Utah Farmer.

'Mickey Mouse', 8 March 1932. © Disney.

Mickey Mouse

In the late 1920s, Gottfredson moved to Los Angeles with the ambition to start a more professional cartooning career. Even though he was first hired by Walt Disney as an apprentice animator on the 'Silly Symphonies' series of shorts, he was quickly asked to take over the four-month-old 'Mickey Mouse' newspaper strip. The comic strip had been launched by the Disney Studios and King Features Syndicate on 13 January 1930, following the tremendous success the 'Mickey Mouse' animated shorts had since 1928. Initially written by Walt Disney himself and drawn by Ub Iwerks, the first serial was a loose adaptation of the 'Mickey Mouse' shorts 'Plane Crazy' (1928) and 'Jungle Rhythm' (1929). Yet after only one month, on 8-10 February, Iwerks handed the artwork over to his inker Win Smith. Iwerks had a fall-out with Disney, because the studio was professionalizing into a uniform style, while Iwerks wanted to keep his own individual style and creative control. Disney and Smith started a new storyline, 'Mickey Mouse in Death Valley', but Disney became too preoccupied with his animation studio, and so he strongly pressured Smith to write and draw the comic series on his own. Smith resisted and also called it quits.

On 17 May 1930, Gottfredson was brought in to continue the feature, both for writing and art duties. What started as a fill-in job for just two months, resulted in a 45-year tenure. His presumed replacement Jack King lasted only two weeks on the strip, from 9 June to 21 June 1930. In the end, Gottfredson turned out to be the artist Disney was looking for. Someone equally skilled in writing as well as drawing, and also more enthusiastic about continuing a daily newspaper comic. While he thought up the plots of his stories himself, from 1934 on, he left the definitive scriptwork to other Disney staff writers. These included Ted Osborne (1934-1949), Merrill De Maris (1934-1942), Dick Shaw (1942-1943) and Bill Walsh (1943-1955). For the artwork, Gottfredson received help from the inkers Hardie Gramatky (1930), Roy Nelson (1930), Earl Duvall (1930-1931), Al Taliaferro (1931-1932, 1936-1937), Ted Thwaites (1932-1940), Bill Wright (1938-1943, 1946-1947) and Dick Moores (1943-1946), until he started inking the strips himself in 1947.

From 1932 to 1938, Gottfredson also drew the 'Mickey Mouse' color Sunday page, which marked the first regular appearances of the character in his trademark red shorts (the animated cartoons were still in black-and-white at the time). Gottfredson drew the Sunday page until 1938, after which he passed the pencil to Manuel Gonzales.

'Mickey Mouse sails for Treasure Island' (21 May 1932).

Style

As an accomplished writer and artist, Floyd Gottfredson is best remembered for the exciting adventure stories he made with Mickey Mouse and his gang. His detailed artwork with compelling backgrounds provided a lively atmosphere, while offering dynamic, fast-paced action and witty slapstick gags. Above all, Gottfredson and his co-writers fleshed Mickey out as a three-dimensional personality. He can be cheerful and heroic, but also has moments of self-doubt and despair. His side characters from the cartoons, like his girlfriend Minnie Mouse, his dog Pluto and the couple of Horace Horsecollar and Clarabella Cow, received the same treatment. They became a close-knit circle of friends, staying loyal to each other no matter what hardships they face. Villains from the animated cartoons, like the cats Peg-leg Pete and Kat Nipp, remained recurring opponents in Mickey's comic strip adventures. In 1932, Gottfredson also gave Mickey Mouse a hometown, originally named "Silo Center", then changed to the more uninspired "Hometown" and, from 1939 on, "Mouseton". In some modern stories, it is referred to as 'Mouseville'. The idea was later imitated by Carl Barks, who gave Donald Duck his home city in the comic book stories: Duckburg.

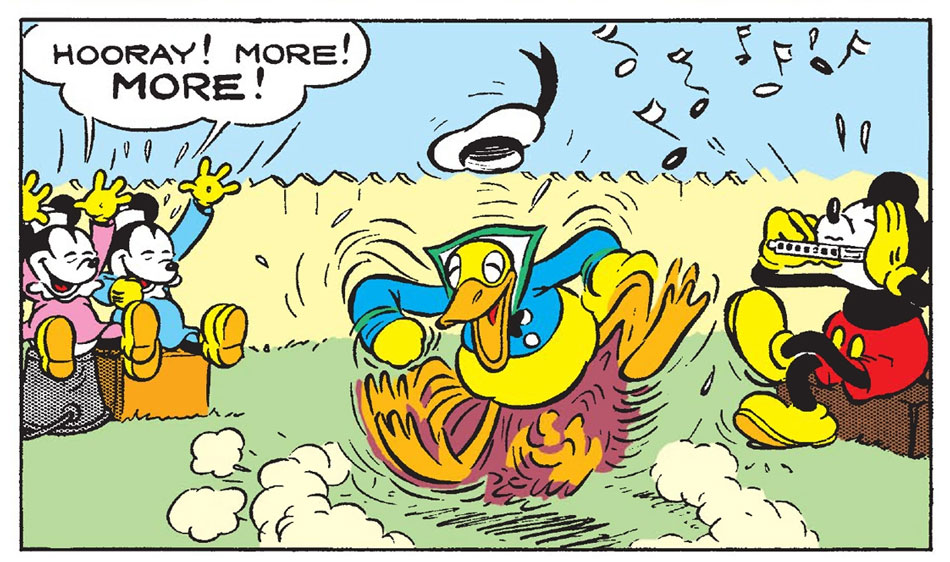

Mickey Mouse Sunday comic of 31 March 1935 with the appearance of Donald Duck (colored yellow at the time). © Disney

Although Gottfredson was never directly involved with the 'Mickey Mouse' animated cartoons, his role in the mouse's global success was still significant. For many children who didn't always go to theaters, Mickey's adventures in the newspapers were their first introduction to the heroic mouse. When the 'Mickey Mouse' cartoons became more adventurous after 1932, their themes and storylines were regularly adapted for the newspaper plots. But most of the time, Gottfredson was allowed to come up with his own spell-binding and engaging narratives. When the Disney cartoons introduced Goofy (1932) and Donald Duck (1934), they paired them with Mickey in various animated shorts. From the mid-1930s on, Goofy became Mickey's humorous sidekick and closest friend in the comics. Initially, the ill-tempered Donald Duck was also featured in the 'Mickey Mouse' strips, but he was quickly phased out by the time he received his solo career on the big screen as well as the newspapers. In later years, Donald and Mickey cross-overs occurred mostly in European comic stories.

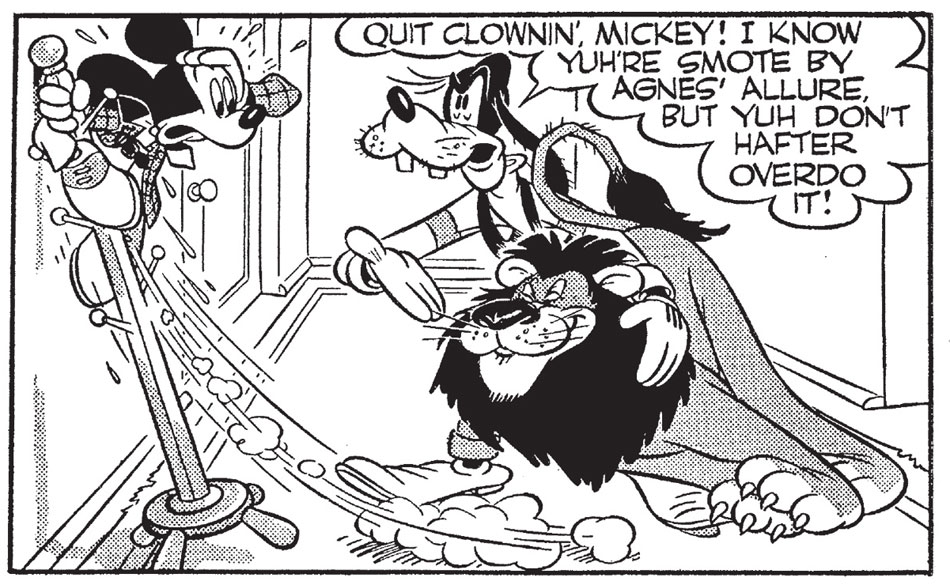

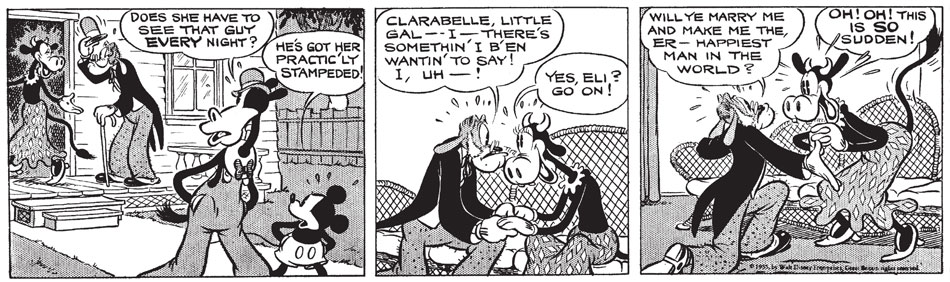

'Goofy and Agnes' (6 May 1942).

On the big screen, Mickey Mouse was initially involved in romantic and slapstick frivolities, occasionally saving his girlfriend Minnie or dog Pluto out of sticky situations. In the comics, Gottfredson quickly took a different approach. He envisioned the mouse as a tough personality, going on many epic adventures. Even the very first narrative, 'Race to Death Valley', is an engaging plot, full of thrills, twists and turns. Mickey is challenged with many problems and ordeals. In one scene, when he thinks Minnie has left him for somebody else, he even contemplates suicide, but after a few attempts, he realizes it's better to face life and find a solution. In the Internet era, the "Mickey's suicide attempts" storyline gained new notoriety for being incredibly dark for a Disney comic. However, it's actually a perfect example of how Gottfredson turned the 'Mickey Mouse' comics into mature adventure stories, filled with thrilling cliffhangers and emotional drama. In the early 1930s, most funny animal comics were simple children's stories, set in a safe, often home-bound universe with no genuine threats. The 'Mickey Mouse' comic, while also written for children, had far more suspense and excitement. Mickey travelled all over the world. Over the years, Mickey went on treasure hunts, solved mysteries and fought pirates, cannibals, master spies, crooks and other enemies on the way.

By 1955, the same year the Disneyland theme park opened, Mickey lost much of his heroic persona. The comic became a more suburban gag-a-day feature, with gags written by Bill Walsh (1955-1962), Roy Williams (1962-1968) and Del Connell (1968-1975).

Mickey Mouse - 'Race for Riches' (15 June 1935) © Disney.

Mickey Mouse: cast expansion

Besides innovative storylines, Gottfredson also enriched Mickey Mouse's universe by creating many new cast members, exclusively for the comics. In the 1930 'Death Valley' storyline, the corrupt notary Sylvester Shyster had been introduced by Walt Disney early on, but Gottfredson made him even more vicious, and continued to use the character in later narratives. Second in line was Butch, a dog-faced thug who made his debut in 'Mr. Slicker and the Egg Robbers' (1930), but later followed his conscience and became a "good" character, even one of Mickey's best friends. Still, he was retired after a few adventures and rarely used for decades. Another notable villain created by Floyd Gottfredson is Eli Squinch, introduced in 'Bobo the Elephant' (1934), a con man and regular accomplice of Pete, who at one point proposes to Clarabelle Cow to get his hands on her inheritance.

'Mickey Mouse Outwits the Phantom Blot'. © Disney.

In 'Mickey's Nephews' (1932), Mickey's two nephews Morty and Ferdie were introduced. In 1937, this idea was copied by writer Ted Osborne and the artists Al Taliaferro and Carl Barks, who gave Donald Duck three identical nephews, Huey, Dewey and Louie. In 'The Plumber's Helper' (1938), Mickey first met the cigar-chomping detective Casey, who fancies himself a skilled crime solver, but is actually dumb and clumsy. Two notable introductions occurred in the story 'Mickey Mouse Outwits the Phantom Blot' (1939). First, The Phantom Blot, a mysterious cloaked villain and master spy. Even though Gottfredson used him only once, later Disney writers and artists turned the Blot into one of Mickey's arch enemies. In his debut story, the antagonist is also unmasked in the end, but later Disney comic creators felt it was more imposing to never show his face to the readers. To catch this criminal mastermind, Mickey is commissioned by Chief O'Hara, a dog-faced police commissioner whose profession, last name and sideburns hint at Irish roots. Together with Casey, he remained Mickey's closest ally in the police force.

'Mickey Mouse and Eega Beeva' (30 April 1948) - © Disney.

The final regular cast addition by Floyd Gottfredson was also his strangest. In 'The Man of Tomorrow' (1947), Mickey met Eega Beeva, a strange person who has trouble understanding life on Earth. He has an odd speech impediment, where he adds the letter "p" to many words and sentences. Contrary to some readers' belief, he is no extraterrestrial or, judging from his loincloth, a caveman. In his debut story, it is established that he is actually a time traveler from the future. Since his civilization is far more advanced, many of our modern-day traditions, customs and phenomena look very simplistic or out-dated to him. He has remained a regular character in later 'Mickey Mouse' stories, particularly in comics made for the Italian market.

Mickey Mouse - 'Isle of Moola-la' (2 & 3 May 1952). © Disney

Head of comic strip department

Between 1930 and 1946, Gottfredson served as head of the comic strip department of the Disney Studios. Apart from the 'Mickey Mouse' comic strip, the division was also responsible for producing other newspaper strips that the Disney Studios provided to King Features Syndicate. Among the most notable were the daily and Sunday 'Donald Duck' strip (drawn by Al Taliaferro), the 'Silly Symphonies' Sunday page with the comic strip debuts of the 'Big Bad Wolf' and 'Bucky Bug' (by Al Taliaferro, Earl Duvall and Ted Osborne), the 'Uncle Remus' Sunday page starring 'Br'er Rabbit' (by Paul Murry and Bill Walsh), the Sunday comic with 'Little Hiawatha' (by Hubie Karp and Bob Grant) and newspaper comic adaptations of Disney feature films and one-shot shorts in the series 'Treasury of Classic Tales' (scripts by Merrill De Maris, art by Hank Porter, Manuel Gonzales, Bob Grant). From 1946 to 1975, Frank Reilly was Gottfredson's successor as head of the Disney comic strip department. While the Disney Studios produced the newspaper comics in-house, the comics that appeared in the monthly comic book titles by Western Publishing were produced by freelance artists directly affiliated with the publisher, for instance Carl Barks, Jack Bradbury and Gil Turner.

'Chesty and Coptie'. Lay-outs by Gottfredson, final art by Bob Grant.

Later comics work

In addition to his work on the 'Mickey Mouse' strip, Floyd Gottfredson did the lay-outs for a story called 'Chesty and Coptie', appearing in a 1945 Chestie giveaway book published by the Los Angeles Community Chest. The finished art on this war-time charity promotion was done by Bob Grant. He also contributed to the 'Treasury of Classic Tales' Sunday page by drawing the comic adaptation of Jack Hannah's Disney short 'Lambert, the Sheepish Lion' (written by Frank Reilly, 1956). In March and April of 1958, Gottfredson wrote the Sunday newspaper story 'The Seven Dwarfs and the Witch-Queen', which served as a sequel to the 'Snow White' movie, with artwork by Julius Svendsen. From August to December of that year, Gottfredson and Svendsen also made an adaptation of 'Sleeping Beauty'. Gottfredson returned to the 'Treasury' feature once more in 1961 by doing lay-outs for the adaptation of '101 Dalmatians' for penciler Chuck Fuson. In addition, he did artwork on Frank Reilly's special Christmas stories with the movie characters 'Cinderella' (1964) and 'Bambi' (art in collaboration with Guillermo Cardoso, 1965).

'Cinderella's Christmas Party' - © Disney.

Recognition

In 1983, Floyd Gottfredson won an Inkpot Award. Posthumously, he was also bestowed with a Disney Legend Award (2003) and inducted into the Eisner Hall of Fame (2006).

Final years and death

Like many early 20th-century studio comic artists, especially at the Walt Disney Company, Floyd Gottfredson remained anonymous until the 1960s. In 1968, he was tracked down by Disney comics enthusiast and collector Malcolm Willits. Luckily, the veteran was still active and able to be interviewed, enjoying his well-deserved recognition. In February 1968, general audiences finally learned Gottfredson's name, when Willits wrote about him in an issue of Vanguard magazine.

Gottfredson retired in 1975, after which the 'Mickey' strip was continued by Román Arambula. For the comic books of Dell/Western Publishing, several of Gottfredson's newspaper comic stories were later reworked and redrawn by Bill Wright, Dick Moores and Paul Murry. Between 1978 and 1983, Gottfredson made 24 paintings with sequences from his classic stories. These were commissioned by Malcolm Willits, who was inspired by the success of the oil paintings that Carl Barks made with the Duck characters. Floyd Gottfredson died in 1986 at his Montrose home in Southern California. He was 81 years old.

Illustration by Floyd Gottfredson.

Legacy and influence

Floyd Gottfredson's art, which evolved from cartoony to more realistic, has been an example for generations of 'Mickey Mouse' artists, both in the USA and those working for European Disney licensees. Already in the early 1930s, European publishers started making their own non-authorized 'Mickey Mouse' artwork. As early as 1931, the Italian humorist Guglielmo Guastaveglia drew stories with Mickey ('Topolino' in Italian) and Kat Nipp. Between 1932 and 1935, Giovanni Bissietta, Buriko, Giorgio Scudellari, Giove Toppi and Gaetano Vitelli also made Italian Mickey comics. Book collections with Floyd Gottfredson's newspaper stories from France, England and Italy all had locally produced cover art. During the 1930s, Serbian children's magazines like Veseli četvrtak, Dečje Vreme and Mika Miš also published unlicensed Gottfredson-inspired Mickey comics by local artists like Ivan Sensín, Vlastimir Belkic, Sergije Mironovič Golovčenko and Nikola Navojev. In 1942, the Croatian cartoonist Veljko Kockar created an anthropomorphic cactus, Kaktus Bata, whose design and stories were very reminiscent of Mickey Mouse. In Thailand, Wittamin drew 'LingGee', a character that was a hybrid of Mickey Mouse, Horace Horsecollar and Popeye. His story 'LingGee Phu Khayi Yak' (1935) plagiarized panels and storylines from Floyd Gottfredson's 'Mickey Mouse' story 'Rumplewatt the Giant'. In Japan, mangaka Shaka Bontaro drew another illegal Mickey story, 'Mikkii no Katsuyaku' ('Mickey's Show', 1934).

'Mickey Mouse' (5 February 1966) - © Disney.

For the comic books by Dell/Western, produced from the 1940s on, artists like Paul Murry and Bill Wright made new stories with Mickey, Goofy, and original Gottfredson creations like O'Hara and The Phantom Blot. However, these stories gradually lost most of their Gottfredson flair, as by the late 1950s the comic book mouse became a more one-dimensional detective. On the other hand, from the 1950s through the 1990s, the Italian Disney creator Romano Scarpa wrote and drew a great many classic 'Mickey Mouse' adventure stories, which had the same atmosphere as Gottfredson's stories, just like those by the American Noel Van Horn from the 1990s on. Between 1990 and 1995, Floyd Norman was responsible for writing the 'Mickey Mouse' newspaper strip and he returned to the adventure continuities in the Gottfredson tradition. The art was done by Alex Howell and Rick Hoover. In 1993 and 1994, the Walt Disney Company launched a branding campaign called "Perils of Mickey" with vintage Gottfredson art from the 1930s, including a line of merchandising and new old-style comic book stories by writer David Cody Weiss and artist Stephen DeStefano. Writer and editor David Gerstein has referred to several classic Gottfredson characters and sequences in the stories 'The Past-Imperfect' (1998) and 'Picturing The Past' (1998), with artwork by César Ferioli.

Dutch writers like Jos Beekman and Robbert Damen have also tried to recapture the Gottfredson touch in their scripts for the Donald Duck weekly in the Netherlands. Dutch artist Jan-Roman Pikula has regularly given Gottfredson creations guest appearances in his 'Mickey Mouse' riddle comics. Among other Disney authors influenced by Gottfredson and his creations have been Emmanuele Baccinelli, José Ramón Bernadó, Federico Bertolucci, Dan Černý, William Van Horn, Daan Jippes and Gerben Valkema.

Also non-Disney authors have mentioned Gottfredson as an influence on their work. In the United States, he inspired Everett Peck, and in Japan he could count Osamu Tezuka among his disciples. In Europe, Gottfredson found followers in Belgium (André Franquin, Willy Linthout, Morris, Marc Sleen and Willy Vandersteen), Denmark (Börge Ring), France (Serge Dutfoy, Elric, Albert Uderzo) and Italy (Federico Fellini, Primaggio Mantovi).

Between 2011 and 2018, Fantagraphics collected Floyd Gottfredson's run on the 'Mickey Mouse' comic in a series of 14 luxury books, edited by David Gerstein and Gary Groth.